This post is part of the LTER’s Short Stories About Long-Term Research (SSALTER) Blog, a graduate student driven blog about research, life in the field, and more. For more information, including submission guidelines, see lternet.edu/SSALTER

by Luke Ramsey-Wiegmann and Raisa Mahmud

CAP LTER – Arizona State University

Red Mountain Highway, part of Arizona 202, cuts through the Phoenix area, one of the hottest, driest, largest, and fastest growing metropolitan areas in North America. This road, eight or more lanes of concrete wide, follows the gravelly channel of the Salt River, the empty central artery of a watershed that has been diverted to sustain growing urban and agricultural societies for over 1500 years. The paved surface of the 202 can reach searing temperatures of over 82 degrees Celsius (180 Fahrenheit). With a rarely-obeyed speed limit of 65 mph, cars and trucks fly along these elevated lanes as if the vehicles themselves are hurrying to escape the heat. But beneath one of the soaring Hot Wheels track-like superstacks is an entirely different scene. Where runoff from the highway and surrounding city is concentrated, a wetland has reemerged in the Salt River’s bed as the unintentional side effect of human water and land management choices.

The Central Arizona-Phoenix LTER (CAP LTER) has monitored nutrient cycles, biodiversity, and human activity in this accidental wetland since 2012, revealing this ecosystem is in some ways a happy accident–a rare occurrence in the age of climate change. The wetland formed after the construction of the interchange of AZ 101 and 202, runoff from which flows through the Price Road Storm Drain into the riverbed. This stormwater combines with runoff from farms on the Salt River Pima-Maricopa Indian Community (SRPMIC) and the Chicago Cubs Stadium in Mesa to provide enough water to support lush marsh and riparian landscapes all year. Parts of this wetland fall under the jurisdiction of SRPMIC, the cities of Mesa, Tempe, and Scottsdale, and the Arizona Department of Transportation. Since the jurisdiction is so complicated, the area is virtually unmanaged, providing an example of how urban wetlands may establish without direct human intervention. Instead of forcing it to fit the norms of landscape architecture and management, the stakeholders have decided to essentially let this wetland design itself.

Credit: Luke Ramsey-Wiegmann, CC BY-SA 4.0.

Credit: Luke Ramsey-Wiegmann, CC BY-SA 4.0.

In the late 2010’s, CAP researchers began to look into nutrient cycling in the accidental wetland, curious if it performed similar functions to Constructed Treatment Wetlands (CTWs). CTWs are designed for wastewater treatment and are becoming increasingly popular because of their ability to remove nitrogen from the water, reducing the chance of downstream algal blooms and dead zones. CAP LTER found that this accidental wetland performed some of the same vital denitrification processes seen in treatment wetlands. In this way, accidental wetlands can potentially serve as a low-cost strategy to improve urban water quality.

Credit: Raisa Mahmud, CC BY-SA 4.0.

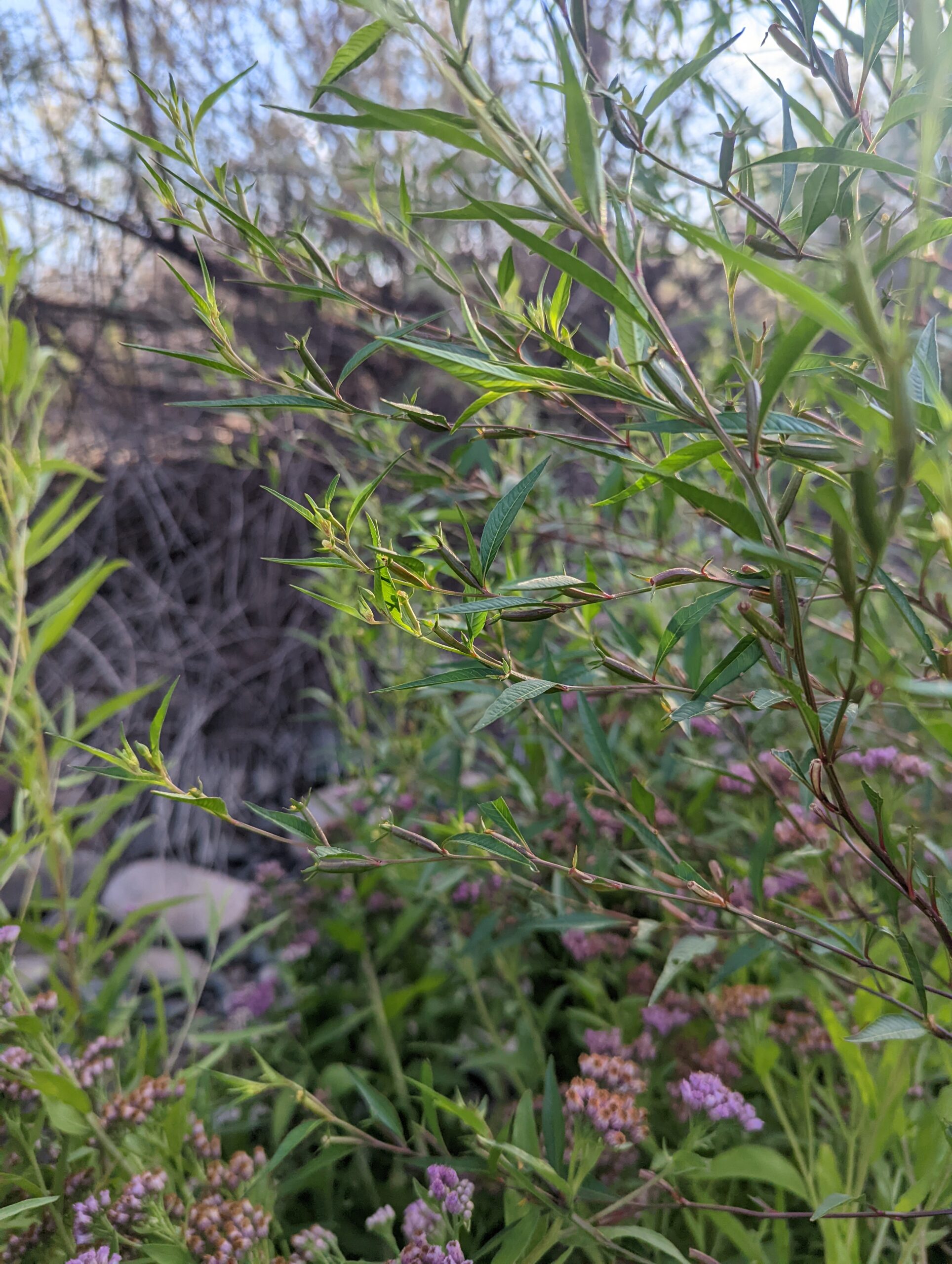

In 2012–four years after the completion of the highway–bird, plant, and reptile surveys in the emerging accidental wetland showed it supported one of the most species rich communities of the urban Salt River. Directly below the rumbling tires, cliff swallows adapted to city life, using these constructed cliffs to build high density housing, much like their human neighbors. The wetland also provided vital water, shade, and forage for waterfowl as they migrate across the Sonoran Desert. The wetland also supported populations of some of the rarest wetland plants in Central Arizona, including Ludwigia erecta (Yerba de Jicotea), the next closest populations of which are found near the Gulf of Mexico in Florida and Texas.

Credit: Luke Ramsey-Wiegmann, CC BY-SA 4.0.

Credit: Luke Ramsey-Wiegmann, CC BY-SA 4.0.

Credit: Luke Ramsey-Wiegmann, CC BY-SA 4.0.

Ongoing animal surveys have shown that wildlife continues to use this urban wetland as a refuge from the dangers of the city, supporting diverse bird communities, rattlesnakes as fat as your wrist, and water-loving mammals such as otters and beavers–who have been rare in the Phoenix area since fur trappers decimated populations in the mid 1800s. The area is more densely vegetated than when CAP’s surveys began, and while much of this abundance is accounted for by prolific introduced plant species such as Arundo donax (Wild Cane) and Tamarix ramosissima (Saltcedar), overall species richness and evenness have not declined. In fact, the rare plants found in 2012, Ludwigia Erecta and Ammania coccinea (Scarlet Toothcup), were more abundant, and Cephalanthus occidentalis (Buttonbush), which had been virtually extirpated in the urban area, had returned to the riverbed at this site. These populations support the dispersal and reestablishment of the species downstream in the urban riverbed, where we found small populations of these species this year. This wetland is the only study site–including preserved and restored areas–where plants considered culturally important to the Indigenous Akimel O’Odham community increased in abundance.

Credit: Raisa Mahmud, CC BY-SA 4.0.

Credit: Raisa Mahmud, CC BY-SA 4.0.

In addition to its importance for local Indigenous communities, the accidental wetland is a refuge for people living without shelter. While access is technically prohibited, groups of people are still drawn to the site by the shade, privacy, and materials it provides. CAP researchers found that people living in the wetland had intimate knowledge of the ecosystem services the landscape provides, from which areas of the wetland had the best fish to which stormwater outflows had the cleanest water. The Phoenix area, like much of the US, is seeing increased rates of homelessness coupled with increasing temperatures. It is little wonder that people are drawn to this unintentional oasis to escape the searing Sonoran heat in the shade of Cottonwoods and Willows–just as people have found refuge by the river for thousands of years.

But are we actually seeing a happy accident? Is this an isolated novel ecosystem, or are we seeing the environment “showing us how it’s done?” Stewarding functional urban landscapes is a complex challenge, and we have tried many approaches to varying degrees of success. Channelized and paved waterways increase flood risk and lower water quality. Recreation areas often become profitable gardens for the wealthy. Restoration areas spend millions of dollars striving to recreate a nostalgic, sometimes myopic, image of ecosystems we paved. But accidental wetlands show us the environment’s ingenuity and resilience, and perhaps a glimpse into the future of urban watersheds. Accidental wetlands remind us that the biosphere is not something to manage and bend to human will, but a collaborator who, given time and respect, can help us cultivate a sustainable future.

Luke Ramsey-Wiegmann (left) is a Ph.D. student in the School of Sustainability at Arizona State University, and the Graduate Student Representative for CAP LTER. Luke studies the urban wetlands of the Salt River, including the Price Accidental Wetland, with a particular focus on plant and animal community composition. With a background in art and environmental education, Luke uses papermaking and printmaking as a way to connect CAP’s ongoing research with local educators, museums, and land managers.

Raisa Mahmud (right) is an undergraduate student in the School of Sustainability at Arizona State University, pursuing a B.S. in Sustainability and a certificate in Water Resources. Raisa is interested in the socio-ecological connections and interactions within wetland and other aquatic ecosystems. Raisa enjoys contributing to CAP’s long-term datasets through fieldwork within the Salt River’s diverse urban wetlands.