This post is part of the LTER’s Short Stories About Long-Term Research (SSALTER) Blog, a graduate student driven blog about research, life in the field, and more. For more information, including submission guidelines, see lternet.edu/SSALTER

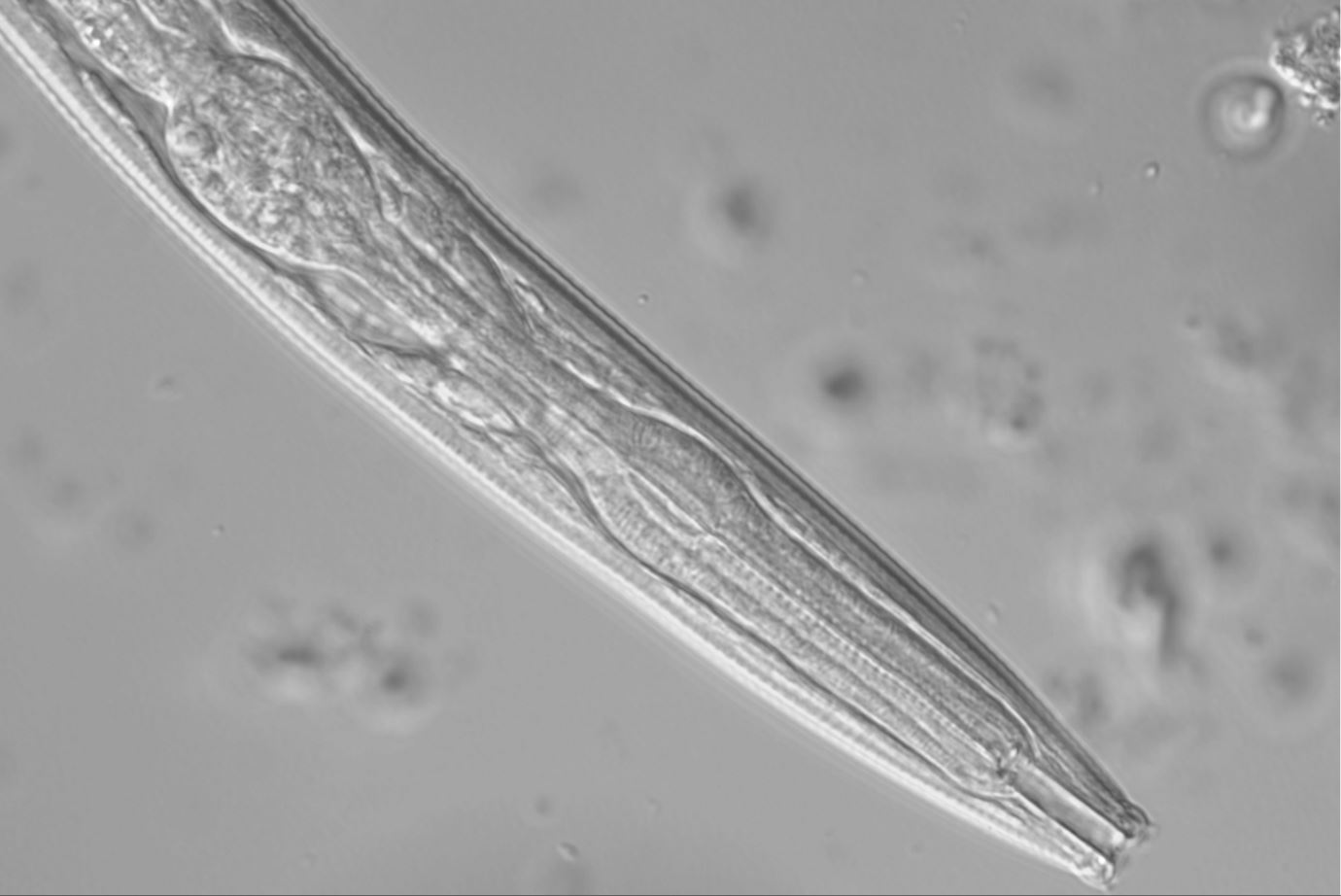

As a new graduate student at the W. K. Kellogg Biological Station (KBS) in 2023, I couldn’t wait to start studying prairie strips: a conservation practice used on Midwest farms where patches of cropland are converted into restored prairies. My research goal was to investigate the invisible but impactful belowground changes to soil health and nematode communities, brought about by these restored prairie patches. I couldn’t wait to (literally) dig deep and better understand how prairie strips support a diverse community of organisms and reduce losses of soil nutrients from cropland.

Credit: Rachel Drobnak, CC BY-SA 4.0.

But, how are prairie strips able to restore agricultural soils and landscapes so well? One of their superpowers is their diverse mixture of plant species. This prairie plant diversity encompasses different roles to complete important ecosystem processes; in other words, they fill multiple functional groups. Grasses, such as Big Bluestem, have deep and robust rooting systems, and grow a large amount of plant material aboveground. Forbs, like Black-Eyed Susans, provide food and habitat for pollinators. At my field site, KBS’s Long-Term Ecosystem Research site (KBS-LTER), 22 prairie plant species work in harmony to bloom all season long, maximize root biomass, and grow into a successful conservation practice!

Credit: Rachel Drobnak, CC BY-SA 4.0.

Credit: Rachel Drobnak, CC BY-SA 4.0.

Credit: Rachel Drobnak, CC BY-SA 4.0.

Credit: Rachel Drobnak, CC BY-SA 4.0.

Credit: Rachel Drobnak, CC BY-SA 4.0.

As I began measuring prairie strip soil health in my samples, I realized the prairie strip experiment at KBS has its own diverse team of scientists, students, and specialists who form our own “functional groups,” if you will. Just like the plants in a prairie strip, our collective efforts allow science to bloom, people to be empowered, and real conservation change to happen.

The scientists

One of my first experiences in graduate school involved meeting with former KBS graduate student, Corinn Rutkoski. Corinn was finishing her dissertation on the soil microbial communities present beneath prairie strips. She explained to me the major findings of her dissertation and work she wished she could continue (check out more research details at Corrin’s website!). One of these ideas was creating a soil food web using her microbial data and higher-order organisms, including nematodes, which I planned to study. Building this food web, I realized, was only possible due to the work Corinn completed and my future research. Corinn’s work was able to reach four years into the life of a prairie strip, but what happens after that? Prairie restoration typically takes 5-7 years to fully establish, and it’s only possible to ask multi-year questions in a long-term experiment like the KBS-LTER. Carrying on Corinn’s legacy with my research is gratifying, knowing we can learn more collaboratively than on our own.

Credit: KBS, CC BY-SA 4.0.

Credit: Rachel Drobnak, CC BY-SA 4.0.

The students

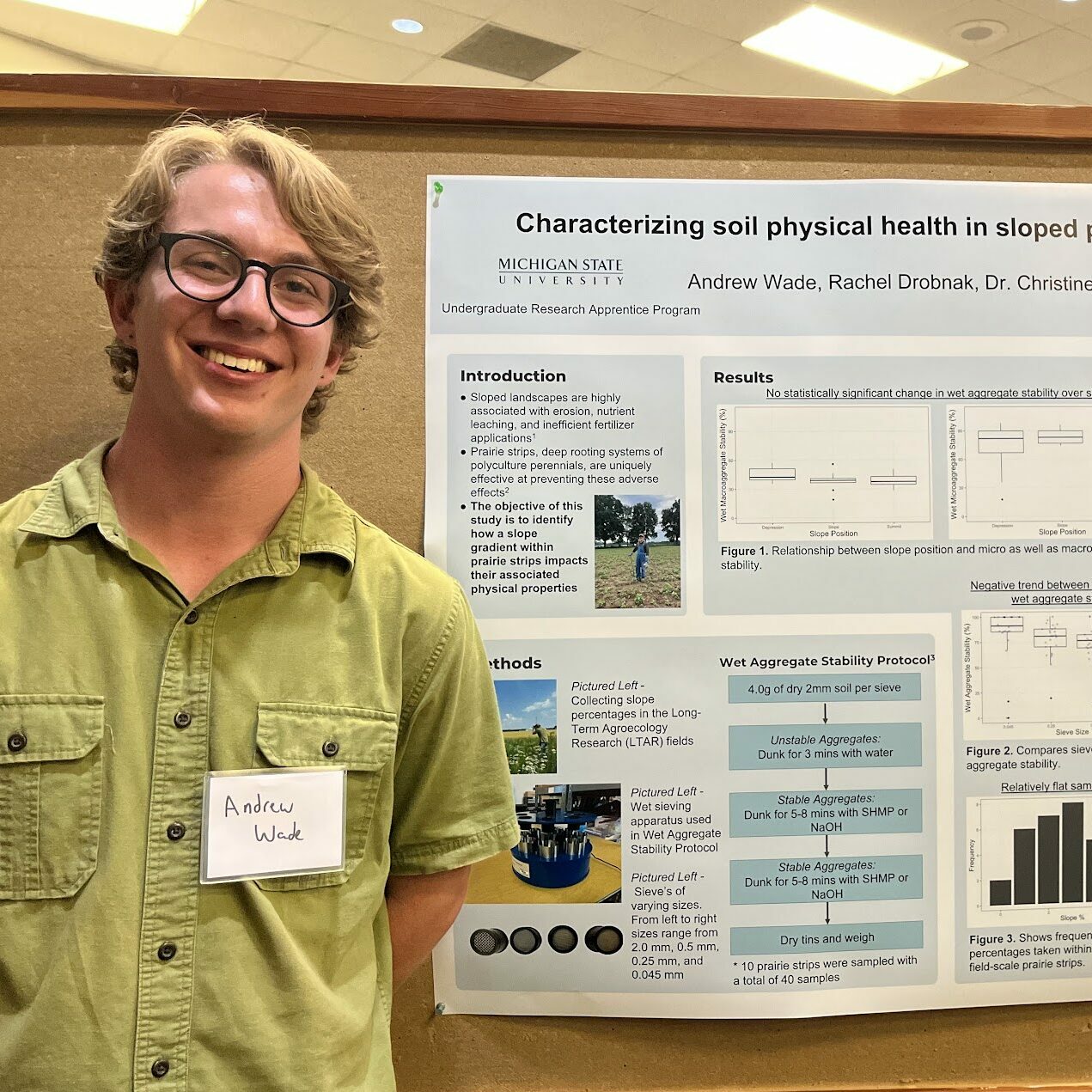

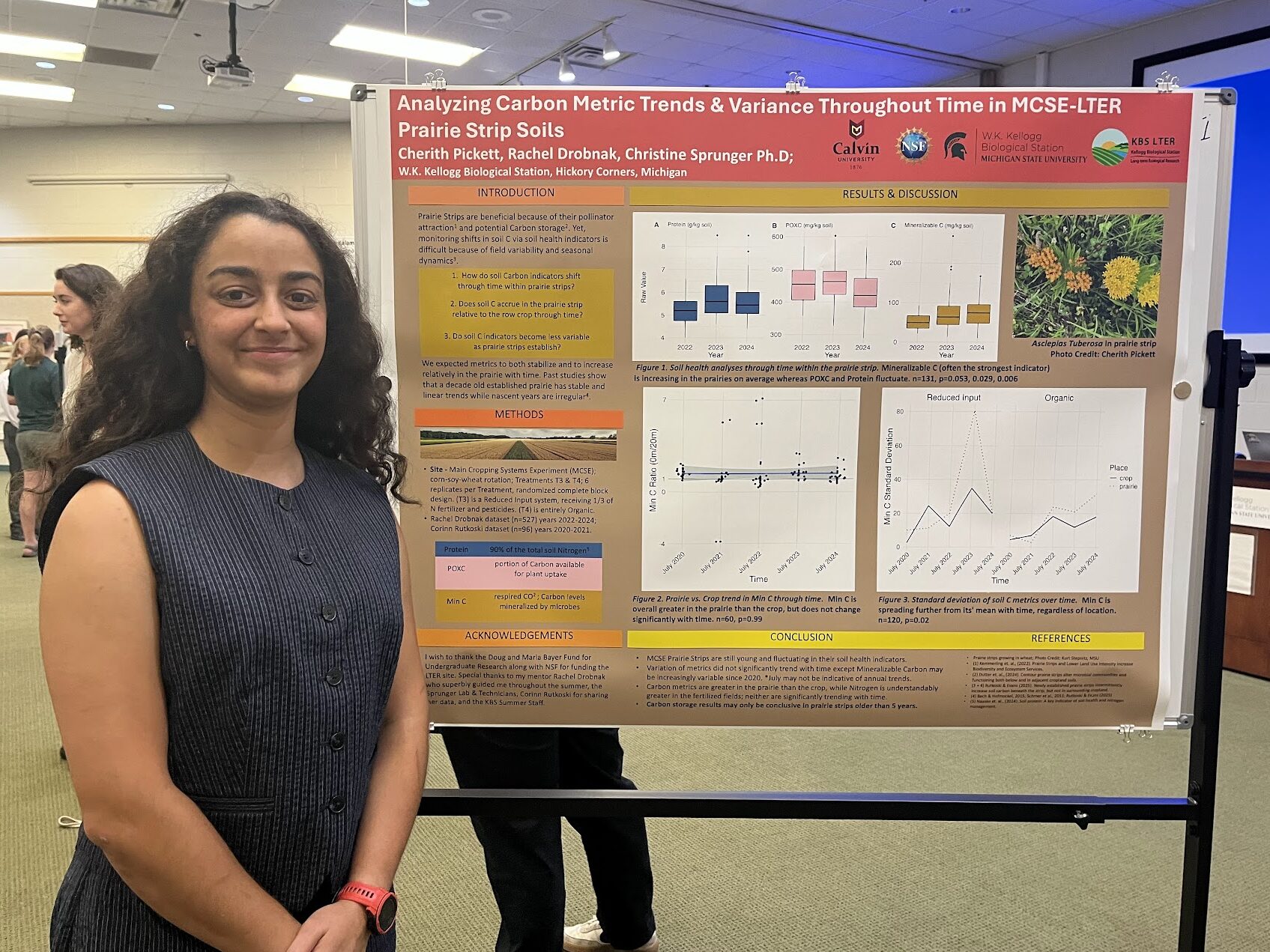

As I dove into my research, I had the opportunity to mentor undergraduates in the 2024 and 2025 KBS Summer Undergraduate Research programs. Andrew Wade, who was a 2024 MSU Undergraduate Research Assistant (URA), had never previously conducted research or developed his own project. Cherith Pickett, a 2025 NSF REU (Research Experience for Undergraduates) student, was interested in studying agroecology in graduate school but had not worked with agricultural soils before. Throughout the summer, the prairie strips were a space for Andrew and Cherith to develop their own research questions, learn soil assays, and analyze datasets. Mentoring Andrew and Cherith through this process was fulfilling because I witnessed their professional growth and their joy spending time in the prairies.

Credit: Rachel Drobnak, CC BY-SA 4.0.

Credit: Rachel Drobnak, CC BY-SA 4.0.

Credit: Rachel Drobnak, CC BY-SA 4.0.

Credit: Rachel Drobnak, CC BY-SA 4.0.

The specialists

Prairie strip research at KBS allows me to do the most fulfilling work of my graduate program: connecting with farmers and landowners. Because prairie strips are a conservation practice, we want people to install them! Within the KBS-LTER, the MiSTRIPS (Michigan Strips) program exists to create a network of scientists and stakeholders who are interested in prairie strips on working farms around Michigan. Outreach specialists, such as Elizabeth Schultheis (MiSTRIPS program director), Tayler Ulbrich (KBS-LTAR, or KBS-Long-Term Agroecosystem Research outreach specialist), and Christine Charles (MSU Extension) expertly organize events, resources, and people to broaden our impact. Through this network, I’ve been able to collaborate in on-farm research with Michigan farmers, present my research at field days, and advocate for prairie strip research to KBS and MSU leadership, including MSU President Kevin Guskiewicz.

Credit: Gavin Hutchings, CC BY-SA 4.0.

Credit: Kathryn Docherty, CC BY-SA 4.0.

Credit: Kathryn Docherty, CC BY-SA 4.0.

Credit: Liz Schultheis

Working in harmony

These important functional groups of prairie strip people – scientists, students, and specialists – each contribute to the success of prairie strip research in complementary and compounding ways. The efforts of research collaborations at KBS found that prairie strips contributed multiple ecosystem services within the first two years of establishment: increased insect abundances and diversity, pollination services, active carbon, and decomposition (Kemmerling et al., 2022, Front. Ecol. Evol.). Over 15 undergraduate students have studied prairie strips during their summer research experiences under the mentorship of 11 early-career scientists. Our network of MiSTRIPS farmers continues to grow every year as well; so far, we’ve added over 50 acres of prairie strips to 11 farms around the state! When I take a moment to reflect on my small contribution to prairie strip science, I feel that I am just one plant species in a diverse prairie of people. Working in harmony, we are contributing multiple “ecosystem services” to science, education, and outreach. What a joy it is to work in a blooming, vibrant community!

Rachel Drobnak (she/her) is a graduate student in the Soil Health & Ecosystem Ecology Lab at Michigan State University. Her research is based at the W. K. Kellogg Biological Station in Southwest Michigan, home of the KBS-LTER. Her research aims to understand how prairie strips alter soil health, and she runs the science social media @dirty.little.worms (on Instagram and Bluesky) to showcase the diversity of soil nematodes.