This post is part of the LTER’s Short Stories About Long-Term Research (SSALTER) Blog, a graduate student driven blog about research, life in the field, and more. For more information, including submission guidelines, see lternet.edu/SSALTER

Credit: Isobel Mifsud

It is 7:20am on a Monday morning in mid-July when my alarm goes off, although I have been awake for almost an hour, listening to other alarm clocks chiming at regular intervals from neighbouring weatherports. We are 158 miles north of the Arctic Circle, and the sun neither rises nor sets, but swings in an eternal, serene loop around the sky. But now the makeshift dawn chorus has begun – the slamming of doors and the crunch of gravel under waterproof boots, and the infernal chime of the alarm as someone hits the snooze button for the fifth time. Rain drops patter comfortingly on the tarpaulin, and I am warm inside the cocoon of my sleeping bag, and I do not want to get up.

The first order of the new day is to head to the dining hall. Breakfast, lunch, dinner, and a seemingly inextinguishable supply of snacks are all supplied by the kitchen staff, five angels that have settled upon this earth disguised as regular humans wearing aprons. First, I fetch my mug from where it hangs on a hook on the wall. Everyone at Toolik has their own mug, labelled with their name, and using someone else’s mug is the basic equivalent of stealing their identity. I make tea, and then try to look casual whilst anxiously surveying the room to see where I might sit, because the awkwardness of the school cafeteria is something you can never actually escape from.

Once breakfast is over, it’s time to begin the great work of Science, which is something I’m still figuring out. Every project at Toolik is assigned a lab, and those of us who find ourselves associated with the terrestrial LTER are mainly housed in Lab 2. A few unfortunate souls are consigned to Lab 4, which is on the other side of camp, so far away as to be practically unreachable unless you are possessed of great determination or a communal bicycle. In lab, I pack my backpack with essential supplies (notebook, measuring tape, chocolate), and head up the boardwalk to the MAT hill. MAT stands for moist acidic tundra, a common ecosystem type in the Arctic LTER sites, but it took me weeks to figure this out, because science is overly fond of acronyms and I felt foolish asking. Walking across the tundra is a bit like trying to walk across a sandy beach in which large sand-coloured rocks have been partially buried at uneven intervals, whilst wearing shoes that are two sizes too big and a blindfold. The characteristic tundra sedges grow into tussocks that form a carpet of miniature hills and valleys, and I find myself losing the battle with gravity almost daily. This makes the boardwalk, which leads directly to the LTER plots, a treasured lifeline to the humble scientist.

Credit: Isobel Mifsud

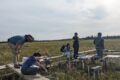

Today I am working in the fertilisation plots established in 1989, harvesting stems of dwarf birch so I can measure how much leaf damage has been caused by herbivorous insects. The morning’s clouds have been swept away by the breeze, and sunlight floods the surface of the earth, unhindered by the trees that do not grow this far north. The tussocks are blooming with little white cotton ball flowers, that make the MAT hill look like it has been sprinkled with sugar. To the south, the Brooks mountains rise like a mirage; to the north, there is only rolling tundra, and beyond that quite possibly the edge of the world. I have pulled the hood of my bug shirt over my head, and my personal entourage of mosquitoes soon arrives, their bodies ricocheting off the material like tiny raindrops. I tie the stems of birch I have cut into bouquets with fluorescent pink flagging tape, and label each with a permanent marker that I keep forgetting to put the cap back on. As I work, I ponder the essential questions that pass through the mind of every scientist at one time or another: “Am I a real scientist? Are the data I’m collecting of any use whatsoever? Should I have gone to law school instead?” And then the yellow-billed loon whistles mournfully from Toolik Lake, and it is time for lunch.

In the afternoon, I make the long journey out to the suburbs, to Lab 4. My task is to carefully snip the leaves from each branch of birch I collected this morning, and arrange them in a neat five-by-ten grid, so I can calculate the total leaf area. The work is slow and monotonous and I drift into a meditative torpor for a while. At 3:30pm, the sweetly scented smell of wood smoke drifts in through the open window, signalling that the stove in the sauna has been lit. I find myself with an hour of free time before dinner, and I open my laptop, with the intention of typing up my notes for the day. I get five words in before it occurs to me that my time would be so much better spent napping in my weatherport.

Credit: Isobel Mifsud

After an hour or so of determined eating, socialising, and anxiously wondering whether everyone else in the dining hall has accomplished more than I have today, it is time for the best part of the evening. The Toolik sauna is undoubtedly one of the primary reasons that so many people in camp claim to have a passion for Arctic research. There is no greater sense of peace than can be gained from sitting in silence in an extremely hot room, safe in the knowledge that when the heat and sweat finally become unbearable, you can hurl yourself into Toolik Lake, from whose surface the ice has only just fully melted. This too is a nearly unbearable experience, but then the sauna is waiting to soothe the aching cold, and thus the cycle can perpetuate for hours.

Although it is nearly 10pm, there is still time to drink tea, watch TV, and play board games. The insistent, unrelenting light makes it very difficult to go to bed, and it is not until I am wrapped in my sleeping bag that I realise how tired I really am. The great work of Science begins again tomorrow.

Credit: Isobel Mifsud

Isobel Mifsud, 2nd year PhD Student in Ecology at Columbia University studies how climate change impacts insect-mediated nutrient cycling, with a focus on how insect herbivores alter the carbon storage potential of shrubs at the Arctic LTER site.