This post is part of the LTER’s Short Stories About Long-Term Research (SSALTER) Blog, a graduate student driven blog about research, life in the field, and more. For more information, including submission guidelines, see lternet.edu/SSALTER

Credit: Michael Cappola

Antarctic Photography Inspires High School Art Project

They say a picture is worth a thousand words. I think they are worth much more. We, as NSF Long-Term Ecological Research (LTER) scientists, students, and technicians, are privileged to work in mesmerizingly beautiful environments. From the alpine glaciers of Colorado, to the tropical rain-forests of Puerto Rico, LTER sites span the range of common biomes found on Earth. The LTER site that I am lucky enough to study is Palmer Antarctica, a sea ice dependent marine ecosystem surrounded by stunning glaciers and stark mountains jutting up from the wavy frozen seas. It’s easily the most beautiful of the LTER sites (a “hot take” and heavily debated opinion amongst LTER researchers), so I often bring my camera to practice amateur photography. If Antarctica is the backdrop, it’s truly difficult to take a bad photo (figure 1).

Credit: Michael Cappola

Photography is a useful tool in the field and supports scientific work. Often, the physical constraints of fieldwork limit the ability to take detailed notes or make diagrams, so a quick photo must suffice. A photo is a welcome addition to a packing inventory for the field or to notes documenting a lab’s condition. Photography can also be an integral part of scientific sampling for those of us who make animal or plant observations. One application where photography is often overlooked is in science communication with the general public. While the science that we do is impactful, our scientific pursuits rarely circulate through the general public; this is especially true when it comes to kids and young adults. Photography provides a low effort means of science communication, and in 2025, it has never been easier to share a beautiful photo with the world. While published manuscripts communicate our results with precision, a simple photo of our LTER site is capable of inspiring awe and curiosity, cultivating an interest as to why one should care about our research in the first place. Organizations like the Sierra Club, the Nature Conservancy, and the Audubon Society have known this for decades. Science informs, but a photograph inspires.

For me, this realization did not come from some wisdom, but was taught to me by my younger sister-in-law, Abigail Willis, who was in high-school at the time. Her art style of choice is painting, and while modest, she is something of a prodigy in my opinion. For my birthday, she wanted to paint my favorite photo that I had taken and I chose one of the Laurence M. Gould in a field of icebergs with the continent in the background (figure 2). This magnificent ice breaker was recently retired by the National Science Foundation and this photo was from its last major oceanographic expedition; a nice painting to commemorate the moment would be a wonderful addition to my home.

Credit: Michael Cappola

I think the exercise of painting and learning about such a fragile ecosystem lit a fire under Abigail. I was delighted and surprised to read a text message from her a few months later requesting more photographs to paint, as well as scientific figures. As the final project for her senior AP art class, she wanted to compile a portfolio of paintings that meshed art and science together in order to communicate the importance and value of studying this remote polar ecosystem at an art symposium. I sent her a handful of graphs and some of my best amateur photographs of the region and waited with bated breath. Below are just a few of the paintings that she worked on. Each piece of work is accompanied with a message that she wanted to communicate with her fellow high-school students, and what the piece means to her.

Credit: Abigail Willis

“The beauty of the mountains is a perfect reflection of the beauty of science. The painting is a nod to how the understanding of science is just as important to nature as its ethereal and timeless beauty. My goal was to bring awareness to the perceived stillness of the mountain to the actual reality of the progressing change through its seasonal temperature cycle. The colors of the sky lead you to think about what can happen in the future if science is left unnoticed and unemphasized.” – Abigail

Credit: Abigail Willis

“I used various thickness of paper (thick to thin) to show the decrease in sea ice area over time. The colors help represent temperature and decreased sea ice strength over time as well. My hope is that this piece demonstrates that art can be beautiful while also being informational and educational. The layered papers thin as time increases into just transparent pieces of film at the bottom, so what will become of the penguin’s habitat once that paper is no longer there?” – Abigail

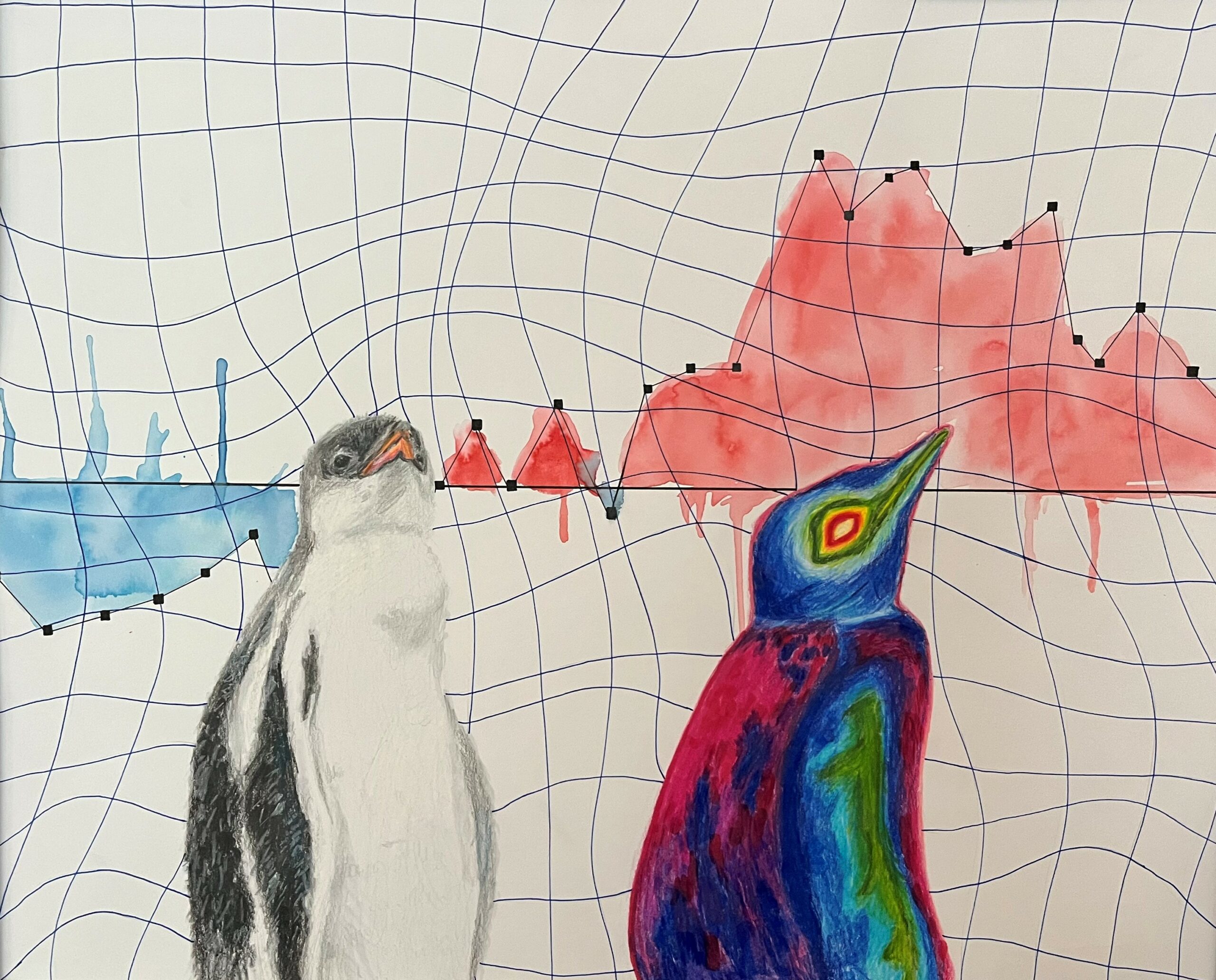

Credit: Abigail Willis

“I wanted there to be a contrast between the realism of the penguin to the realism of the scientific data. The warped lines of the graph represent the warped perception of global warming through society, and how information can be misconstrued. The Gentoo chicks are to be a representation of the real life impacts that temperature increase can have on nature, and the animals that are the essential life and heart-beat of that environment.” – Abigail

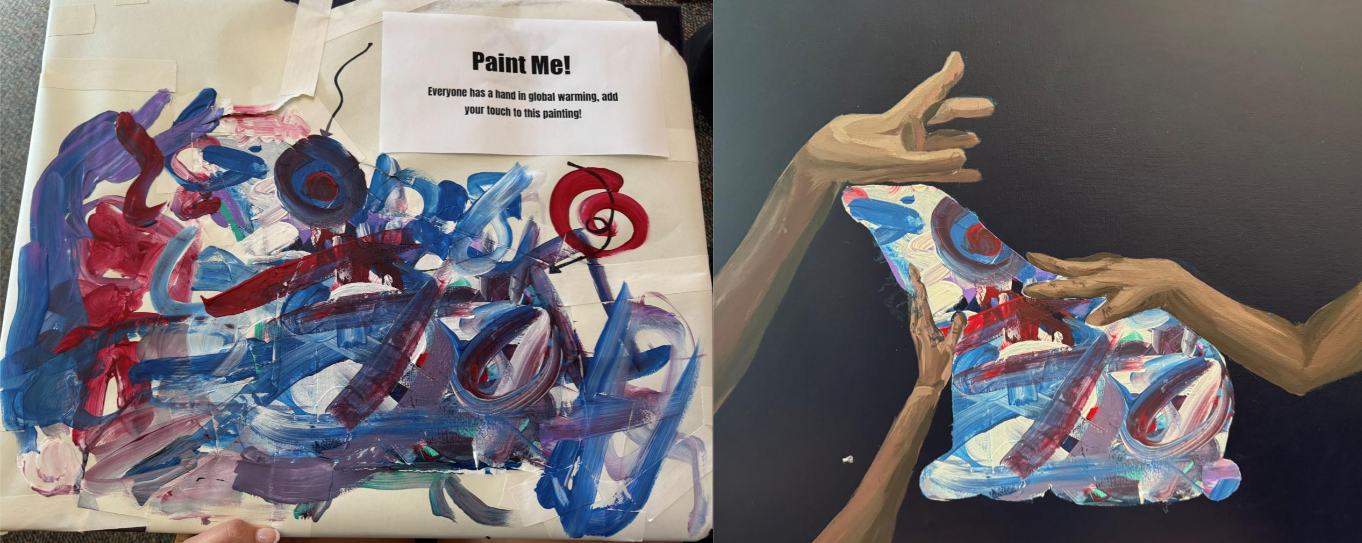

Credit: Abigail Willis

“For this painting I wanted to symbolize choice. I painted hands reaching for the polar bear to symbolize that we all have a hand in the environment and the animal population, it’s how you leave your mark that matters. I painted the polar bear white and taped off the canvas around it, and had an art show where I had everyone add a mark to the painting until it was covered. With a selection of colors and brushes, they painted everything from smiley faces, hearts, and abstracts. All it takes is one person to inspire others, once the first person puts a brush stroke on the canvas, others follow suit. This is just as easily applied to science, it only takes one person to spark the fire that can inspire us all. It’s our choice how we want to interact with the world, and I believe a big part of that is the choice we have to involve ourselves and others.” – Abigail

I am still not completely sure of what inspired Abigail to take on this task. Fellow graduate students know that it’s often the creativity in data visualization that is the most difficult part of science communication, so I hope the reader appreciates the difficulty in what she set out to do. Perhaps she was interested in communicating Antarctic science with her friends? Perhaps she was captured by stunning beauty of polar seas? Perhaps she was just looking for a unique project for the art class? Whatever the reason, the impacts of her efforts are clear. During the art symposium, Abigail discussed difficult and complex topics like human driven climate change affecting polar ecosystems, and explained how the Palmer LTER program seeks to understand the impacts of those changes. Throughout the symposium, well over 150 people viewed her work and received her message. We would consider ourselves lucky if half of that number read about our scientific endeavors. While the complexities and details were likely likely lost in translation, there are now 150 more people who might think about Adelie penguins and Antarctic glaciers when they read the news about climate change or climate change policies. That human connection is invaluable and it can start with a photo. So before you head to the field again, I challenge you to dust of your camera, photograph everything, and share it with the world. Even simple phone photos will do just fine. You do not have to be an expert photographer for your photographs to have a massive impact, reaching further than you could have ever predicted. Happy snapping!

Author Biography

Michael Cappola is a PhD Student at the University of Delaware studying polar coastal oceanography under the guidance of Dr. Carlos Moffat. Before academia, he served 8 years in the United States Navy as a nuclear submarine SONAR operator, where listening to humpback whales and taking oceanographic measurements ignited his passion for physical oceanography. His research is primarily focused on upper ocean dynamics and response to a changing climate in the West Antarctic Peninsula, which has seen significant glacial retreat and sea ice season reduction. While at sea collecting data in support of the Palmer Long Term Ecological Research program, he often practices amateur photography to share the wild and unique ecosystem with the world. (mcappola@udel.edu)