by Laura Lilly (CCE-LTER grad student rep)

In August 2019, the California Current Ecosystem (CCE) LTER program undertook a 32-day Process Cruise to sample the ocean off California. We left San Diego Harbor under sunny skies and smooth sailing conditions and headed north toward Monterey, California. The goal of our month long cruise was to track water filaments that are upwelled in near-coastal waters off central California and flow out to the open ocean several hundred miles offshore. We measured various aspects of the biological production associated with filaments: viruses and bacteria, phytoplankton and zooplankton, along with the nutrients that fuel their growth. Our 2019 cruise was the 9th cruise of the CCE-LTER site, which was started in 2004. The program consists of a core body of scientists from Scripps Institution of Oceanography and collaborators from numerous other institutions, as well as visiting scientists and volunteers from around the world. Our 2019 cruise included participants from as far away as Canada, France, Luxembourg, and Ghana!

Below is one of our blog posts throughout the month. You can check out the entire cruise blog at: https://cce.lternet.edu/blogs/201908/.

Recovering MOCNESS nets can be exciting in rough seas. They really do look like creatures from the watery depths!

Credit: Laura Lilly

One of the core measurements we conduct on our Process Cruises is zooplankton net tows. We do these tows to determine which organisms associate with the various water parcels we are measuring. We expect to see differences in zooplankton communities that live in highly-productive filament waters that have just been upwelled and contain lots of nutrients and phytoplankton food for zooplankton versus ‘blue-ocean’ waters farther offshore that have much lower nutrient concentrations and may host a more subtropical zooplankton community. We also expect to see differences in the numbers and types of plankton in different depths of the ocean.

When you do zooplankton tows, you bring a lot of monstrous-looking creatures onboard. Sometimes we get Phronima hyperiid amphipods, which were the inspiration for the 1979 movie Alien; occasionally we pull up red tuna crabs, small lobster-like crustaceans with very sharp claws; and even a rare vampire squid, a small purple creature with big black eyes, Dumbo ears, and tissues between its tentacles that resemble vampire cloaks. But one of the craziest monsters we have is the net we use to capture and sample these organisms: the MOCNESS!

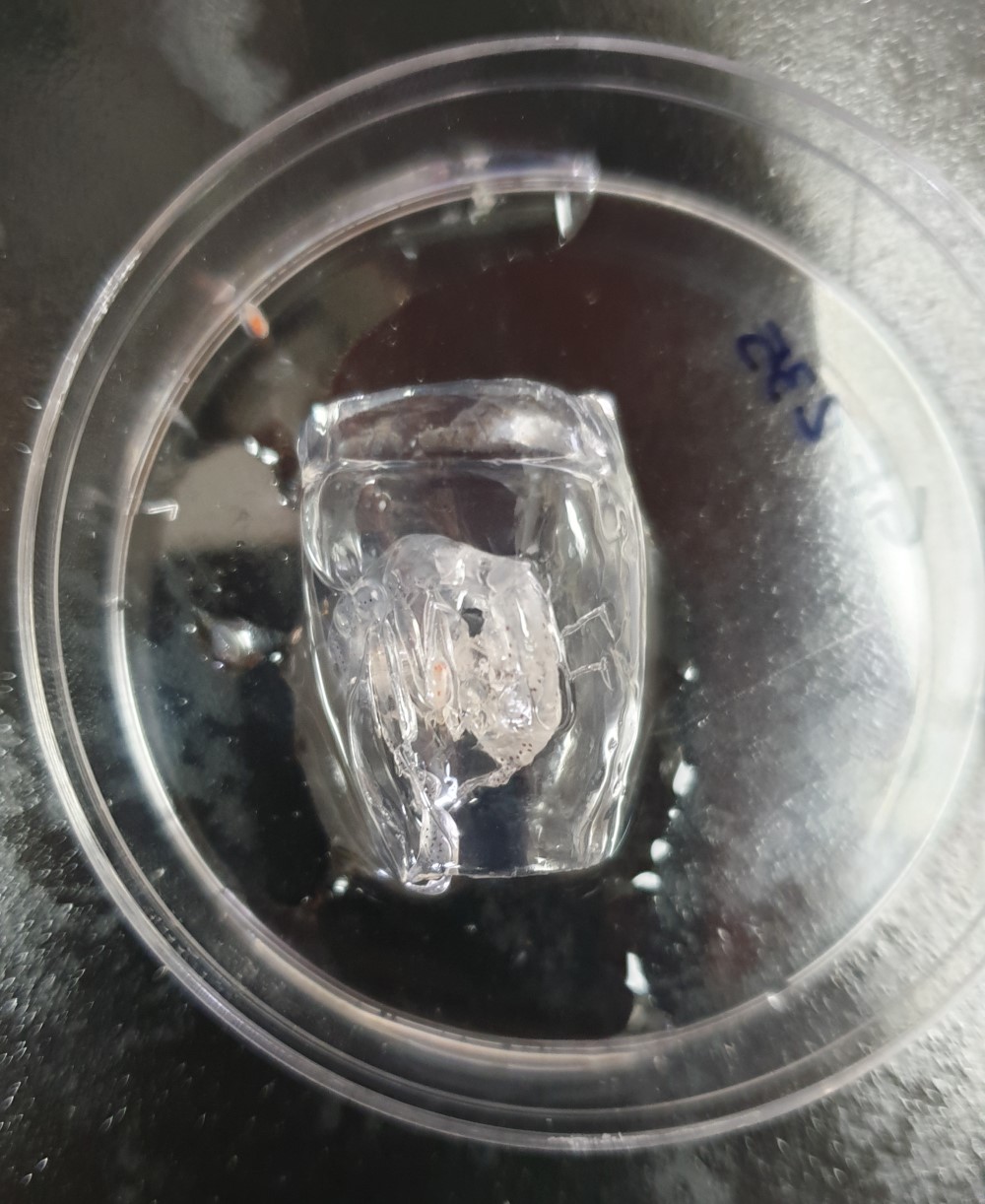

A Phronima hyperiid amphipod curled up in a hollow salp ‘barrel’ (body case). Phronima carves a salp’s body out and uses the barrel as a house – like a slightly morbid version of a hermit crab. Photo courtesy of Pierre Chabert.

Credit: Laura Lilly

Assuming you haven’t been living under a rock for the past hundred years, you will probably recognize MOCNESS as a play on Scotland’s Loch Ness Monster. MOCNESS stands for Multiple Opening/Closing Net and Environmental Sampling System, and was developed by Peter Wiebe at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. If you can process that behemoth of a name, you will get clues about what the MOCNESS does. Most of our plankton nets, such as Bongo nets, have simple circular ‘mouths’ that stay open for the whole net deployment: they go down to depth open and come back up still open, so if we sample down to 200 meters we are actually collecting animals everywhere between the surface and 200 meters. That comprehensive sampling is fine for a lot of the research questions we ask (aka: “Who is present in the upper ocean off San Diego versus Monterey?”), but sometimes we want more information about which animals live at specific depths. As its name implies, the MOCNESS has multiple nets (10 on our current setup!) attached to one frame, and they can be opened and closed in sequence to sample different depths. If you want to compare the zooplankton living at 1000 meters versus 100 meters, you can program separate nets to close at each of those depths. The MOCNESS also has oceanographic instruments to measure water temperature, salinity, oxygen, and fluorescence, so we can get information about the physical water profile in addition to zooplankton specimens.

Most of our MOCNESS tows on this cruise sample down to 450 meters, although occasionally we sample to 1000 meters. Those deep tows can last over three hours, which doesn’t even include the net washdowns afterward! majority of the sample from each net filters down to a plastic jar attached to the end of the net, but once the nets come back on deck, we hose them down to make sure we collect all the animals that may have gotten stuck in the net mesh. Net washdowns sometimes feel endless, but they can be very important: one of the vampire squids we caught a couple of days ago was stuck halfway down the net, and we wouldn’t have collected it if we hadn’t done the net washdown.

Each of the ten MOCNESS nets has a plastic ‘cod end jar’ attached to the end. These jars collect most of the organisms that get caught in the nets, and bring them back to the surface for us to sample. Four cod end jars are visible here as the grey cylinders with drainage holes and duct tape bumpers.

Credit: Courtesy of Lance Wills

Net washing time is also essential for taking in the afternoon sun (or sometimes early morning pre-dawn night air) out on deck, and for keeping an eye and ear open for passing whales. Today we started our third cycle, and we were graced all day by the presence of fin whales. Their deep exhaling sighs and broad backs were sometimes just 50 feet away from our ship. The sound of a fellow mammal emerging from the depths of the ocean to release a breath of air never gets old. Plus, all those whales are a sure sign that there are zooplankton around to feed on!