Nearly thirty years ago, I left my home in a small California beach town with the dreams of an 18-year old university student ready to study biology, chemistry, and medicine. Yet, decades later, after spending time in a University of California biochemistry lab and teaching classrooms full of chemistry students, I returned home so that my own kids could enjoy the idyllic beach town life. Of course, I taught chemistry again, but I found few students interested in moles and stoichiometry. When given the opportunity to teach locally-relevant marine science to juniors and seniors just up the coast from my hometown, I found a public education job with purpose.

Developing a full-year marine science curriculum for high schoolers based on a couple marine biology classes from 1999 proved challenging. I quickly realized that I needed to dive back into current research and connect with the local scientists at the University of California at Santa Barbara. The ARETs program (Authentic Research Experience for Teachers) provided the perfect opportunity for making these connections. Taking the time to read the current scientific literature about marine heat waves, then discussing the conclusions with the scientists compiling and analyzing the data, gave me the basis for designing accurate, research-based lessons for my students about local sea surface temperatures.

temperature, and seaweed coverage at

Gaviota State Beach. Credit: Melissa Moore.

One activity that seems to make an impact on my students is mapping the sea surface temperatures along the coastline of Santa Barbara County during the late fall months. Students note that the temperatures in the southeastern part of the county and Channel Islands are typically approaching 70 degrees Fahrenheit at that time of year, influenced by ocean currents moving northward from Mexico and the Los Angeles area–while the Lompoc area, nearest our school, remains in the low 60s due to its exposure to the colder California current. We discuss how these currents meet at Point Conception resulting in an area of great biodiversity, and how this might change if marine heatwaves shift warmer temperatures further north on a more regular basis.

Diving Back into the Laboratory with Sea Urchins

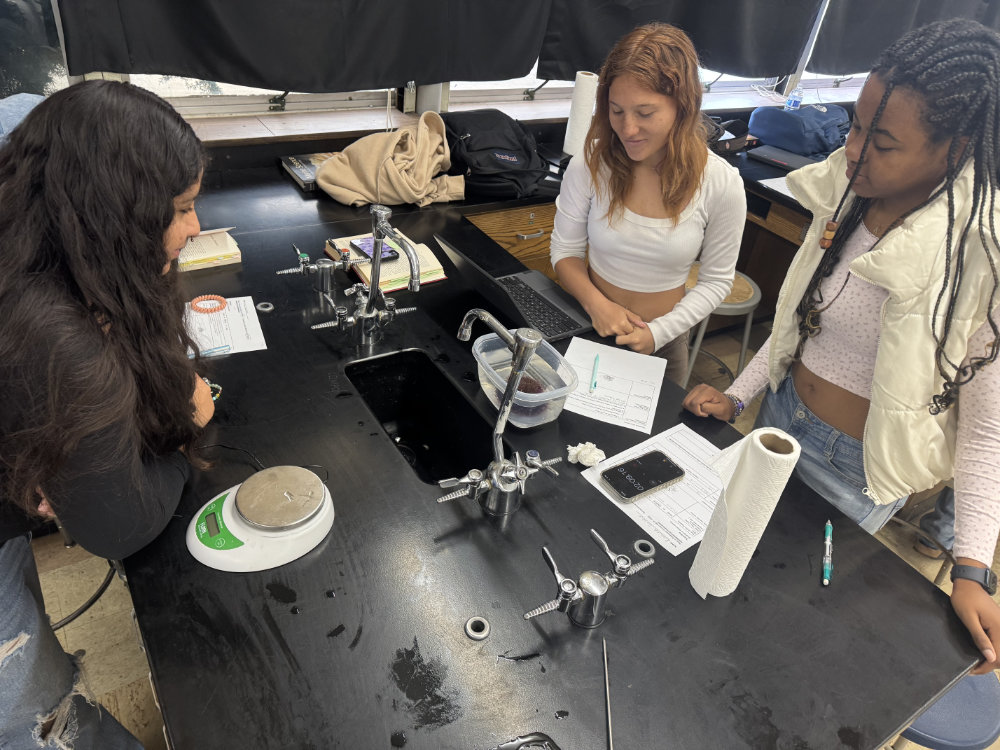

The best part of the ARETs program was the opportunity to return to a University of California science laboratory. In the Hofmann Lab, I set up experiments testing the kelp consumption of purple sea urchins at different temperatures. Later, I brought this experiment to my high school students so they could get to experience a real university experiment. My students tested whether purple sea urchins preferred giant kelp harvested by UCSB researchers in the local kelp forests or red seaweed harvested from the rocks of the intertidal zone. When given the option, the purple urchins clearly preferred the kelp, though some purple urchins consumed the red algae when it was the only option available. Purple sea urchins also seemed to prefer the stable but warmer indoor temperatures of the classroom to the fluctuating outdoor temperatures in our brief study. Students of all academic abilities were curious about the sea urchins living in the buckets of sea water under my desk. Marine science students would bring in their friends at lunch to show them the sea urchins. Of course, many students were disgusted to learn that people eat the reproductive organs, uni, of these sea urchins as a local delicacy.

Mentoring the Next Generation of Scientists With Locally-Relevant Projects

While at UCSB, I also connected with Dr. Jenny Dugan and members of her lab to learn how they are studying our local sandy beach ecosystem. The Dugan Lab studies the diversity of arthropod communities consuming kelp-based wrack on Southern and Central California beaches. These arthropods are important because they are a vital food source for our local shorebirds, most notably the endangered western snowy plover. The lab also shared with me their procedures and protocols for setting up mesocosms with sand, kelp, and a talitrid arthropod, the beach hopper. Using these procedures, we could investigate the feeding preferences of this locally important invertebrate in the classroom.

The city of Lompoc, where I teach, only has one publicly accessible beach due to the presence of Vandenberg Space Force Base. That beach is partially closed March 1 through November 1 to protect snowy plover nests. The nearest public beaches outside of town are 35-45 minutes away so Lompoc students are naturally curious about the importance of the snowy plovers in the nearby marine ecosystem due to the closure of their local beach. So, I worked with students to modify the Dugan Lab’s beach hopper experiments for the classroom. Students screamed and squealed as they tried to transfer ten hopping arthropods from my large collection bucket to their mesocosms prepared based on the protocols from UCSB. We found that beach hoppers seemed to have a preference for the feather boa kelp that grows nearshore over the giant kelp that grows further out in the kelp forests. Possibly this is due to the nutritional quality of the kelp, a question that UCSB researchers are working to answer.