The CoRRE Working Group continues to develop new ways to study plant community change across the globe.

Credit: Jill Haukos, CC BY-SA 4.0.

Global projects must start somewhere

In the early 2010’s, four graduate students noticed something odd. Long-term nitrogen and phosphorus addition plots at the Konza Prairie LTER, meant to be replicates of one another, often ended up with completely different plant communities. No one knew why. For the four students who studied plant community change, it posed a problem. What was driving the different responses in plots located less than 10 meters away from each other?

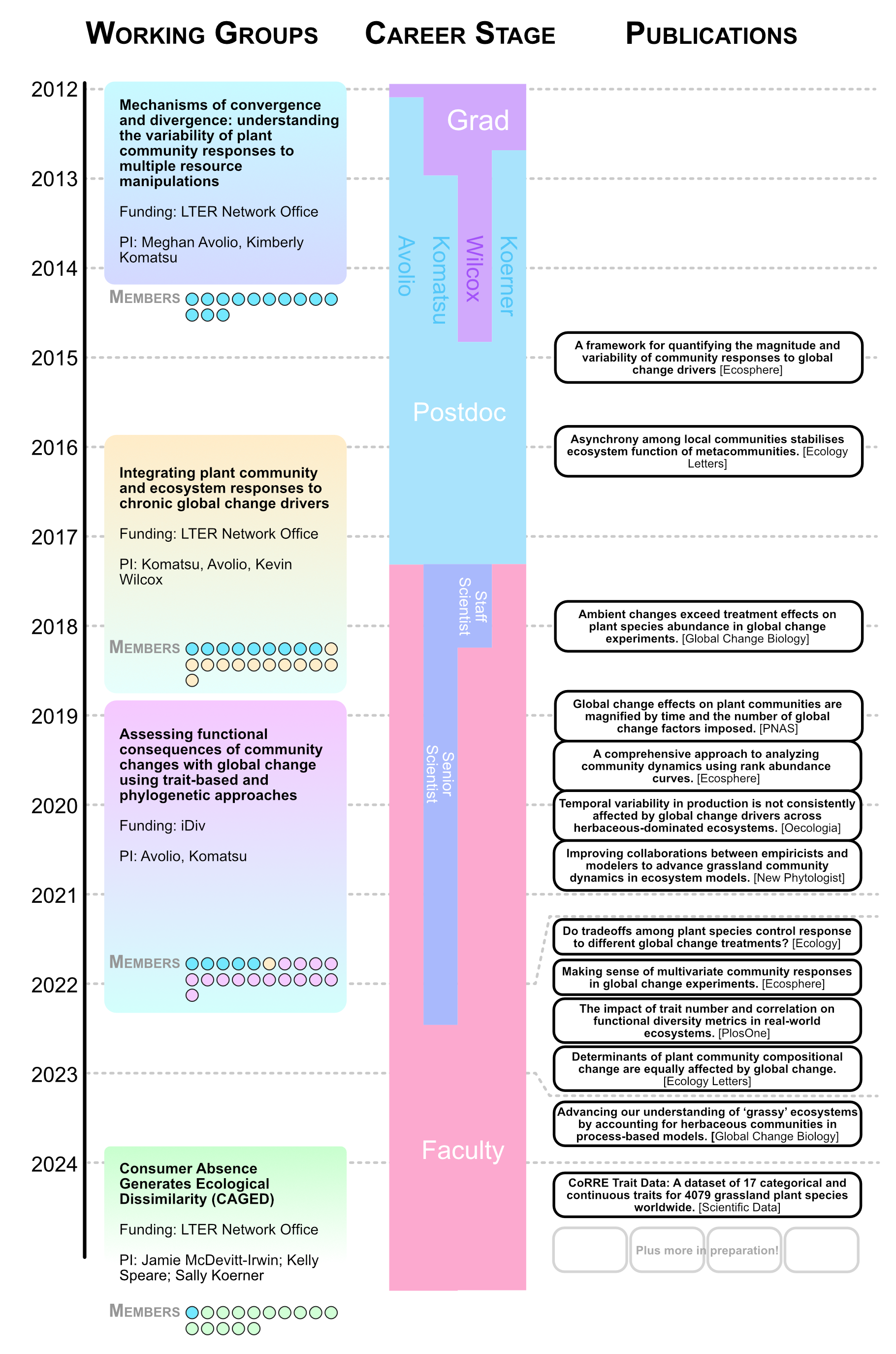

That question—how predictable are plant community responses to anthropogenic change—sent the four students, Meghan Avolio, Kim Komatsu, Kevin Wilcox, and Sally Koerner down a decade-long rabbit hole. The students led three working groups, two funded by the LTER, to understand these patterns of community change, including that natural variability that spurred their initial interest. “It just captured our imagination,” says Avolio, who is now a professor at Johns Hopkins University.

Their work has been strikingly successful. The group collated data from resource manipulation experiments, like the one at Konza, into the Community Response to Resource Experiments (CoRRE) dataset, a global dataset ripe for exploring community change. They developed a new method to study variability of community change, then put it to test in the CoRRE database. They probed that dataset for other common community responses, resulting in a dozen papers with more in the works. And, spurred on by questions they couldn’t quite answer with the CoRRE database, they spent several years creating a companion dataset with plant trait data. That new dataset, the CoRRE Trait database, was just published, and the team is using it to answer new questions about how these plant communities respond to global change. Those data are now publicly accessible and ripe for exploration.

This project is a sterling example of the value of synthesis science. The group’s analysis has shifted understanding of plant community response to global change. The two datasets have potential to answer years worth of questions at a global scale. But more than all, the project formed a centerpiece of four young researchers’ careers—who are all now faculty. This group demonstrates how a single investment in a synthesis project has far reaching effects.

Credit: Kim Komatsu, CC BY-SA 4.0.

Why communities?

Plant communities determine how an ecosystem functions. Species differ in the extent that they fix nitrogen, attract pollinators, or store carbon, for example. When a plant community changes, the ecosystem begins to function differently; as global change shifts plant communities across the globe, understanding these shifts is central to predicting how our planet will function in the future.

Across the globe, researchers have studied these kinds of changes through resource manipulation experiments. For example, at the Phosphorus Plots experiment at Konza Prairie, where Avolio, Komatsu, Wilcox, and Koerner worked as students, researchers added phosphorus and nitrogen to different experimental plots. Then, over two decades and counting, they watched the plant communities change over time. The results simulate what the prairie might look like in the future as human activity increases the amount of nitrogen and phosphorus in the area. Similar experiments manipulate other resources—water availability, light, carbon dioxide, or nutrients—to simulate global change in ecosystems all over the world.

Curious about ecosystems beyond the prairie, Avolio, Komatsu, Wilcox, and Koerner found examples from three other experiments where plant communities diverged in the same way they did in their plots at Konza. They were inspired to search for more data, and applied for LTER working group funding. But in their first working group, it was quickly apparent that such a compiled dataset would be useful at a much larger scale: taken together, these experiments had the potential to reveal how global change as a whole will alter the planet’s plant communities.

Credit: Meghan Avolio, CC BY-SA 4.0.

Want an answer? Build a dataset

The CoRRE database now contains 138 datasets on plant community composition from 70 different locations across the globe. At the end of the first working group, the team had collected 50 such datasets, and the dataset has continued to grow steadily since then.

Using these data, the team was finally able to answer a version of their original question about plant community responses to global change. Global change manipulations changed which species were present as well as the relative abundance of each species in plots. These kinds of changes were consistent around the globe. Moreover, plant community change was greater when experiments manipulated multiple anthropogenic drivers simultaneously.

While the team added nutrients to their experimental plots at Konza, the whole prairie was simultaneously facing effects of global change in the real world, such as increased nutrients and a warmer climate. Surprisingly, for a majority of the 2,000 plant species they studied across the CoRRE database, actual ongoing global change had an even stronger effect on plant communities than the manipulations designed to simulate global change. In other words, communities changed as much or more in untreated plots as they did in treatment plots. That shifting baseline often wasn’t considered when interpreting the results of these individual studies, but was essential context when trying to parse the effects of the experimental manipulations.

Other studies blossomed once these data were compiled, too. The group found that ecosystems were more stable if their individual species displayed varied responses to change, adding to a long-running theme in ecology to study stability. Other forays revealed the complexity underlying these kinds of global studies. One study showed that productivity across 27 plant communities responded inconsistently to manipulations, suggesting that global change induced changes to productivity depend highly on local conditions. Another showed some evidence that plants that respond positively to one kind of treatment (ie. nutrient addition) respond negatively to another (ie. warming), suggesting most species display resource tradeoffs. These results were again weak at a local scale, suggesting other site specific factors exert a stronger influence on communities.

Credit: Rachael Brenneman, CC BY-SA 4.0.

Methodological advancement

Avolio began exploring a novel approach to studying community composition changes during the first LTER working group in 2012; one of the initial group’s key papers was a methods paper highlighting the potential of this technique. A follow up paper leveraged the second LTER working group to refine their methods. Her technique integrates two different methods designed to study how global change treatments affect communities: rank abundance curves, which compare changes in species richness, evenness, rank, and composition, clarify which kind of changes drive dissimilarity metrics, which show the magnitude of the difference between communities.

The group then applied this approach to real data from the CoRRE database. In a 2022 publication, they show that the method is more effective than other simpler, more common approaches when applied to real data.

This connection highlights an important distinction in how the group orchestrated their second round of funding. The first LTER working group, which ended in 2014, resulted in the seeds of both the new methodological approach and the dataset. As the dataset was ripe for exploration, the group realized that taking full advantage of these threads required expertise in two separate approaches to ecology: empiricists, who study ecosystems using collected data, and modelers, who rely on simulated approaches.

The second LTER working group, which was funded in 2016, intentionally included both empiricists and modelers within their ranks. It was a daunting task. “That second meeting [of the second LTER working group] was so painful,” says Wilcox. “Modelers would be saying one thing, empiricists would be saying another, everyone is throwing out acronyms left and right.”

But the group persisted. “We came to this realization that actually everyone was saying the same thing. Everyone had the same goals, but we were just talking about it differently,” Wilcox says with a smile. “All of a sudden, once we realized that, everyone started pulling forward towards similar goals, and then we made real progress.” The nine papers and one R package published from this group show that the effort was worth it.

Incomplete information

When the last of the LTER working group funding wrapped up in 2016, the group still felt their questions were unresolved. Two of their hypotheses, that there might be links between plant community and productivity responses to experimental manipulations and that resource tradeoffs are common across species, only had weak evidence to back them up or refute them.

Elsewhere in ecology, researchers were using plant functional traits, rather than species identities, to predict how an ecosystem responds to global change. Functional traits are inherent characteristics of species that describe how they act: a species might require a lot or a little nitrogen or grow faster or slower in hot weather. Together, these traits define how that community functions. If climate change favors several hot weather species that happen to grow quickly, for example, it’s straightforward to predict that the system will become more productive in a warmer future.

Using plant traits would provide a new way to understand community responses to global change, the group’s overarching goal. But trait data were scarce. Few studies collected trait data at all. Where data existed, they were full of gaps, inconsistent in which species or traits had information. That is a nonstarter when using these data for predictions.

Over the three years following the conclusion of their second LTER working group, the team worked to fill in those missing data.

Using a variety of gap-filling analyses and a deep literature search, the team generated a dataset of 17 different traits for over 4,000 plant species across the globe. The result is a complete trait dataset—the first of its kind at a global scale—that is ready for the kinds of analyses that predict ecosystem response to global change.

The work is a logical continuation of the first two LTER working groups, but Avolio and Komatsu reached beyond the network for support. The project was funded by iDiv, the German Centre for Integrative Biodiversity Research in Leipzig. The collaborators, who included Avolio, Komatsu, Wilcox, and Koerner, also included an international cast of ecologists.

Organic Growth

Synthesis ideas are often big ones: LTER synthesis projects connect ecosystems, cross discipline boundaries, draw on different types of data and analyses, and involve a dozen or more collaborators. Rarely does two years of funding allow a group to completely explore the idea.

What two years of funding does do is allow a group to show that their idea has real scientific merit and promise. In this case, the group used that initial funding to refine their ideas, collect data (often the most challenging task of any synthesis project), and to foster the initial collaboration between empiricists and modelers.

By the end of that first round of LTER funding, the group knew they had something bigger that was worth pursuing. They leveraged that work into two subsequent rounds of funding. “I think being able to walk in with a full database that we know is clean and functional was key” says Komatsu. “Having the time and the funding to create the CoRRE database has really led to everything else that we’ve been able to do, and hopefully will lead to more.”

An investment in synthesis is also an investment in people. At the outset of the first working group in 2012, Avolio, Komatsu, Wilcox, and Koerner were graduate students. The four were postdocs during their second round of funding. Now, they’re all tenured faculty.

The products—publications, datasets, funded proposals—helped them advance their careers. But the benefit of this synthesis group is deeper than that. “We were building friendships because of these working groups. I think that’s what made all the difference for us,” says Komatsu. “I don’t think I would be where I’m at if it wasn’t for these things,” adds Wilcox.

Credit: LTER Network Office, CC BY-SA 4.0.

Synthesis science, from the LTER Network Office’s perspective, is about more than just science. Sure, asking big questions across ecosystems and picking away at answers with real data has uncovered breakthroughs in ecology, full stop. But synthesis groups also develop relationships—between individuals, between ecosystems, between disciplines. Those relationships persist long after any sort of working group funding is exhausted.

At the LTER Network Office, we recognize the value of synthesis to science and to people. Each year, we fund several new working groups. Our one meeting SPARC groups are designed to let researchers determine if an idea is worth pursuing, much like the initial working group allowed Avolio, Komatsu, Koerner, and Wilcox to figure out they were on the right track. Our full working groups let researchers dive deeper into analysis and churn out products. We’ve also added synthesis training for graduate students in our SSECR course. It’s an attempt to accelerate synthesis skills for a much broader contingent of our network, and also provides important mentorship and work on an actual project as part of its curriculum.

“Every in-person working group I’ve been to has been just a blast, and I feel like I’ve grown as a person,” says Koerner. “I’ve made friends, and we’ve just deeply sat and thought about science together. Working groups are just so critical for reminding us that science is supposed to be fun. It’s hard, but it’s also supposed to be fun.”

Our RFP for SPARC working groups is open now. An application might just lead to a decade or more of cutting edge science.

Credit: LTER Network Office, CC BY-SA 4.0.

by Gabriel De La Rosa