This post is part of the LTER’s Short Stories About Long-Term Research (SSALTER) Blog, a graduate student driven blog about research, life in the field, and more. For more information, including submission guidelines, see lternet.edu/SSALTER

Minneapolis-St. Paul urban LTER (MSP) is one of the newest sites to the LTER network. We study the diverse urban ecosystem of the Minneapolis-St. Paul Twin Cities metropolitan area in Minnesota. The Urban Watershed team at MSP has ongoing monitoring in four urban parks in the City of St. Paul to study the role that urban trees play in controlling the flow of water and nutrients through the ecosystem.

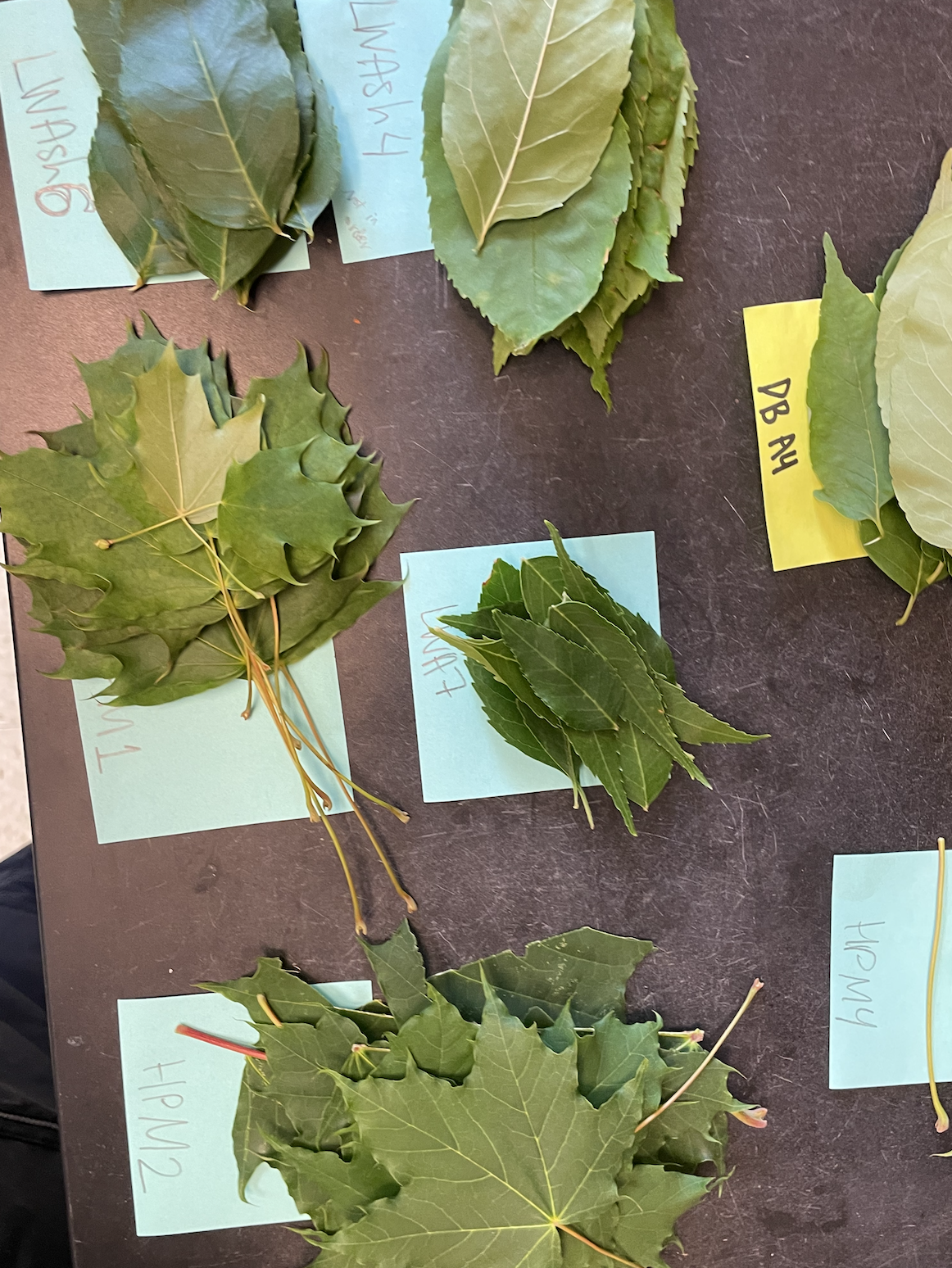

This past summer, the Urban Watershed team hosted two REU students for the urban ecohydrology project. Frankie Mele was a REU student from University of California, Los Angeles, studying ecology. For the REU project, Frankie went out with the fieldwork team every week and collected leaf samples to look at metal toxin concentrations in these urban leaves. Aidan Reynolds was a REU student from Macalester College (MN), studying urban ecology. Aidan joined the fieldwork team, but also went out with Postdoc Jeannie Wilkening to collect leaf samples from University of Minnesota campus trees to analyze the drought adaptation status of a few different species of urban trees during the hottest time of the day. The foliar samples were then brought back into the lab for leaf water potential measurements.

This SSALTER blog is modified from the REU students’ weekly blog posts. Check out the fieldwork snippets they have done this summer! Both Frankie (in-person) and Aidan (virtual) will be presenting their work at the upcoming AGU 2023 fall meeting.

What does a typical fieldwork day look like at the urban watershed team?

Credit: MSP LTER, CC BY-SA 4.0.

Credit: MSP LTER, CC BY-SA 4.0.

The team kicked things off by performing routine maintenance on their sap flux sensors, throughfall (rainfall that makes it through the tree canopy) collectors, soil moisture sensors, and temperature gauges situated at four parks throughout St. Paul.

At various points this season, the team would find that a couple of their tree monitoring sites had been fully trashed and ripped apart. Thankfully, all was not lost, and the team was able to clean up the sites and reestablish both the sap flux sensors and throughfall collectors. This was a good learning experience as it gave us a better understanding of what doing research in highly populated urban areas can look like.

What does a typical lab day look like at the urban watershed team for throughfall chemistry analyses?

Credit: MSP LTER, CC BY-SA 4.0.

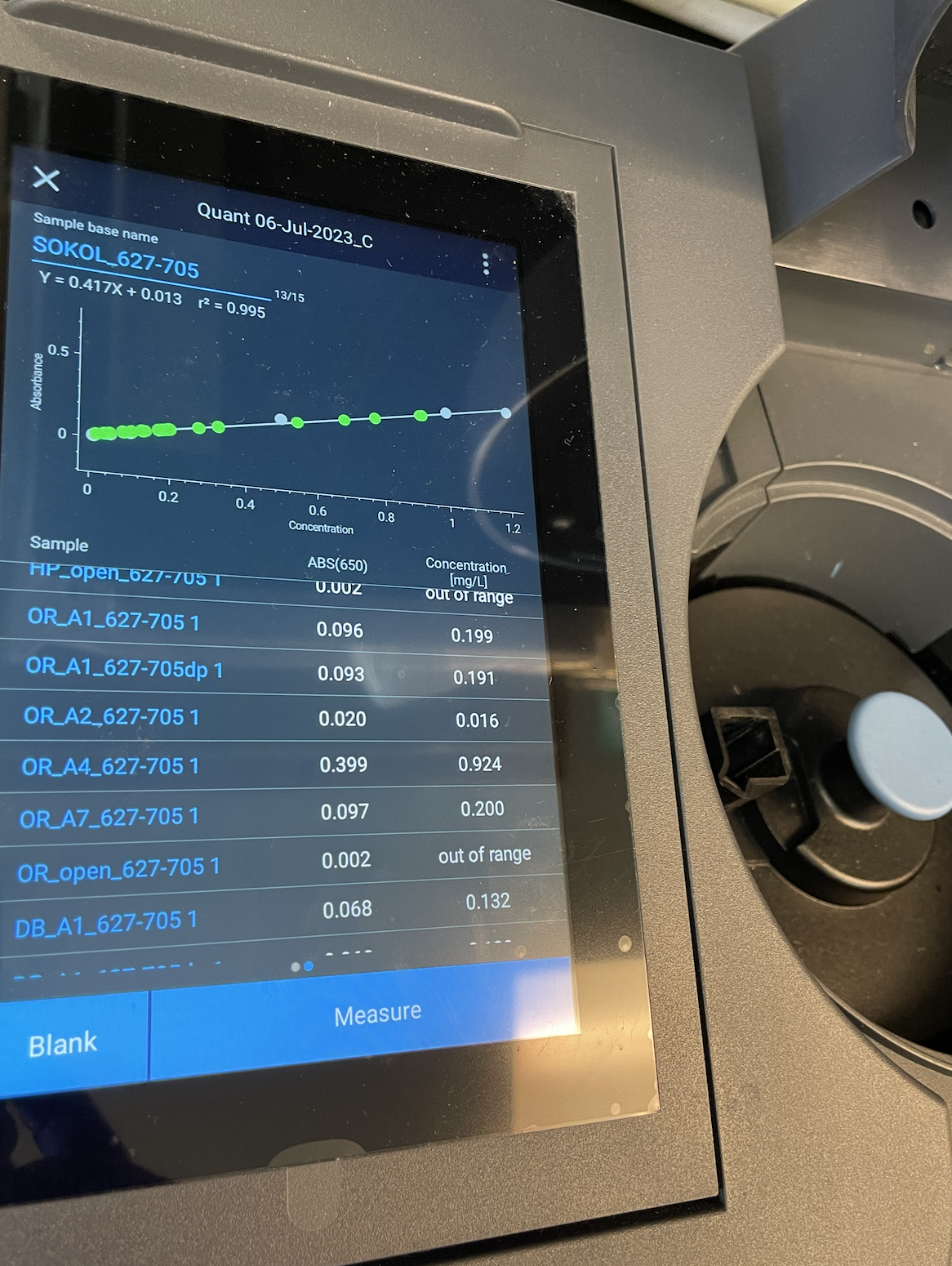

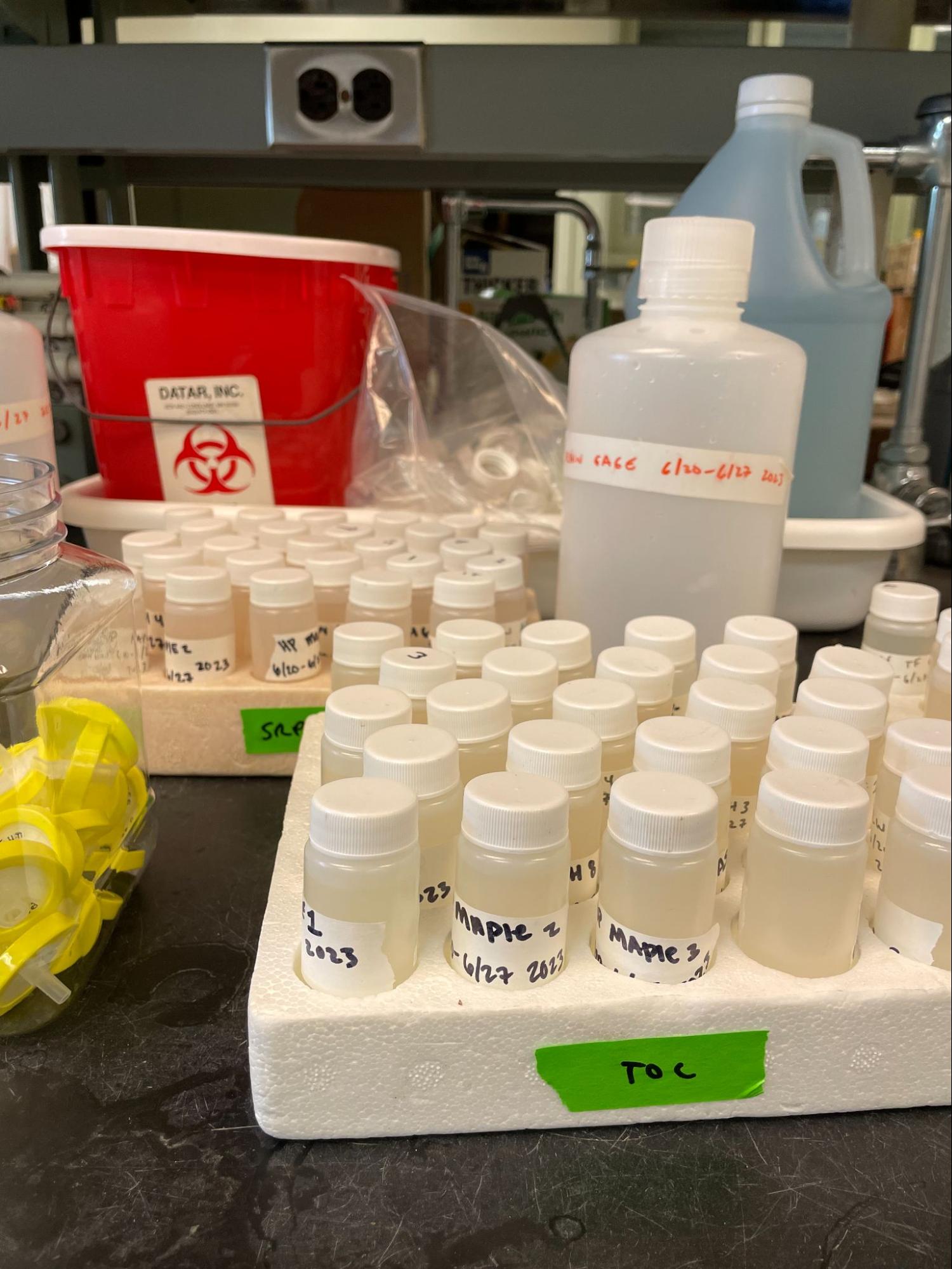

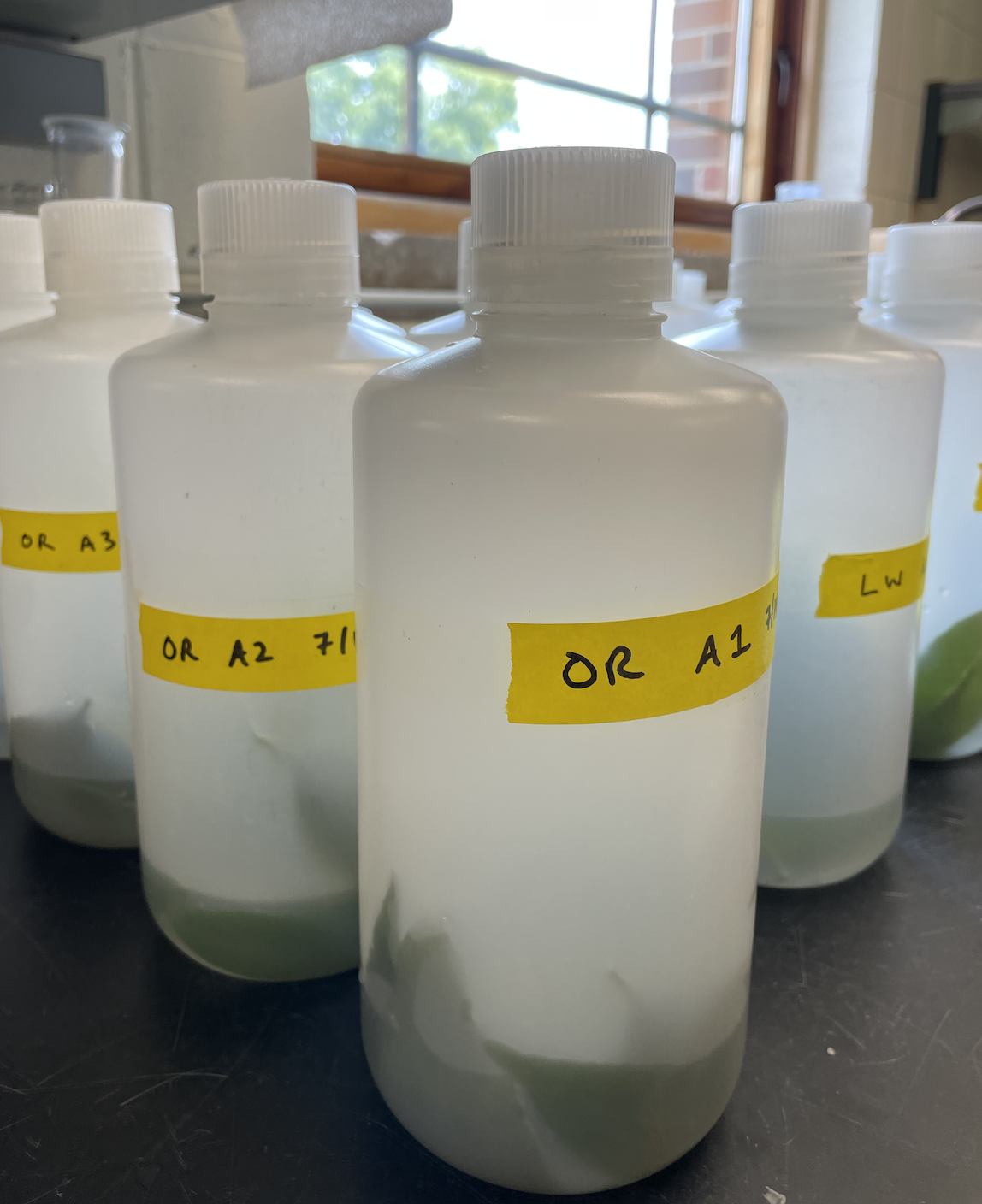

Back in the lab, Frankie and her mentor Lucy Rose organized the throughfall samples collected from the sites (thank you rain!!). They measured and labeled a whole lot of samples to be sent off to a different lab to quantify the nitrogen and carbon concentrations. The project was a success: Frankie and Lucy were able to quantify the concentration of soluble reactive phosphorus in all samples using the UV-visible spectrophotometer in the local St. Paul lab.

How water-stressed are the University of Minnesota campus trees?

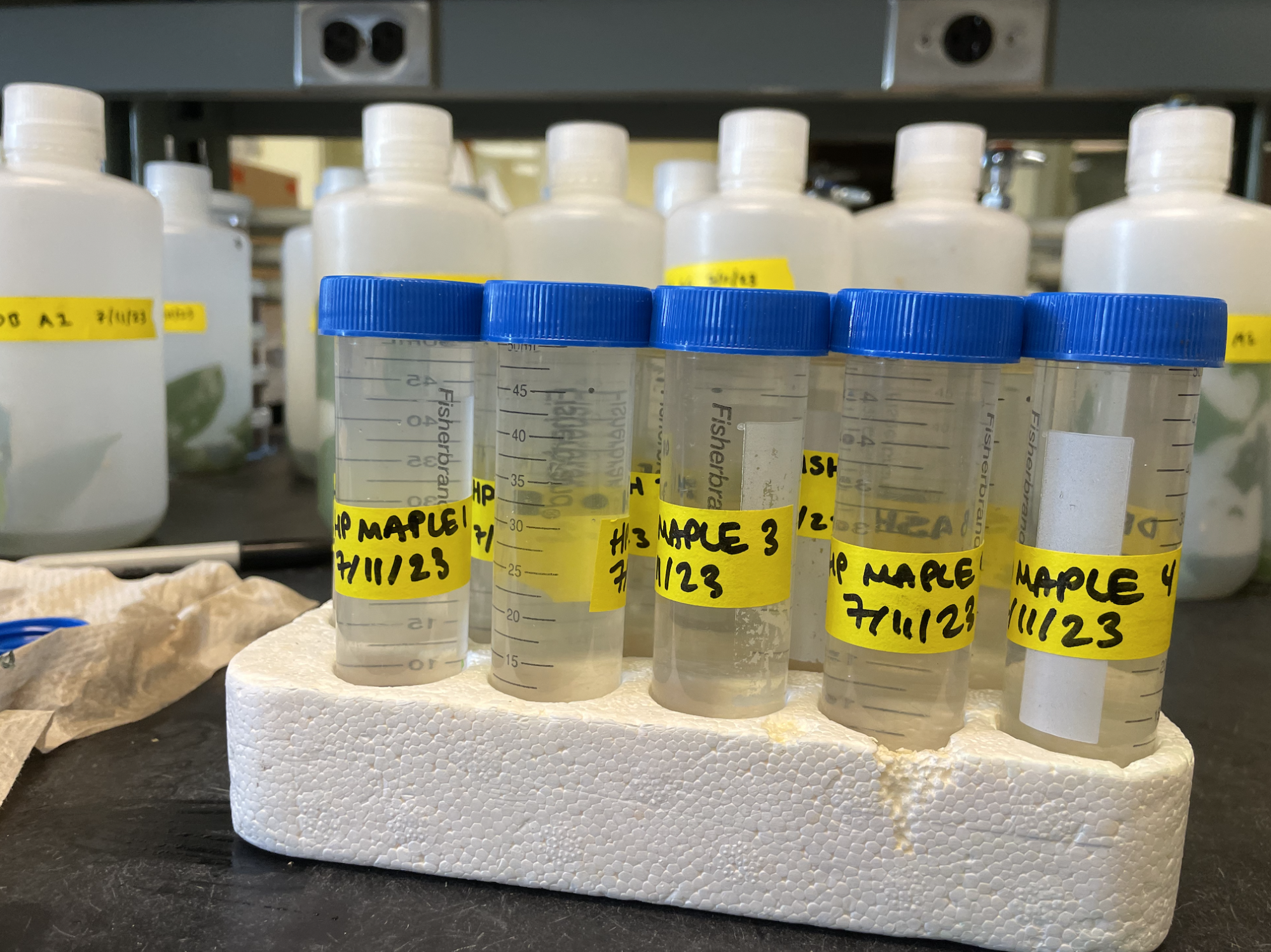

Minneapos-St. Paul went through a period of drought this summer. Local trees are clearly stressed for water, but how stressed are they? This is where Aidan’s project comes in. This summer, Aidan learned to use a pressure chamber (or pressure bomb) in order to calculate leaf water potential. A leaf is constantly pulling water up from the core of a tree as the air around it dries. The amount of pressure the leaf exerts on the water inside it correlates with the water stress of the tree—the more water stressed, the tighter the leaf holds onto its existing water. Back in the lab, these leaf samples are put in a pressure chamber and are gradually pressurized. The pressure at which we see water coming out of the cut is the leaf water potential, which tells us each tree’s level of water stress.

Aidan was all over the University of Minnesota Twin Cities campuses collecting foliar samples from a variety of urban tree species across an environmental gradient (e.g. physical water constraints due to impervious surface). He and mentor Jeannie Wilkening would venture out across the study sites at solar noon (around 1:30pm in Minnesota), when plants initiate maximal stomatal opening, and bring their samples back to the lab for analysis. The most difficult part of the fieldwork is that these leaves were collected during the hottest part of the day! Aidan had to run around like a chicken with its head cut off to collect foliar samples in the 95 degree weather. Along the way, they witnessed an abundance of urban wildlife (squirrels, hawks, turkeys, oh my!).

What are the heavy metal levels on urban tree leaves?

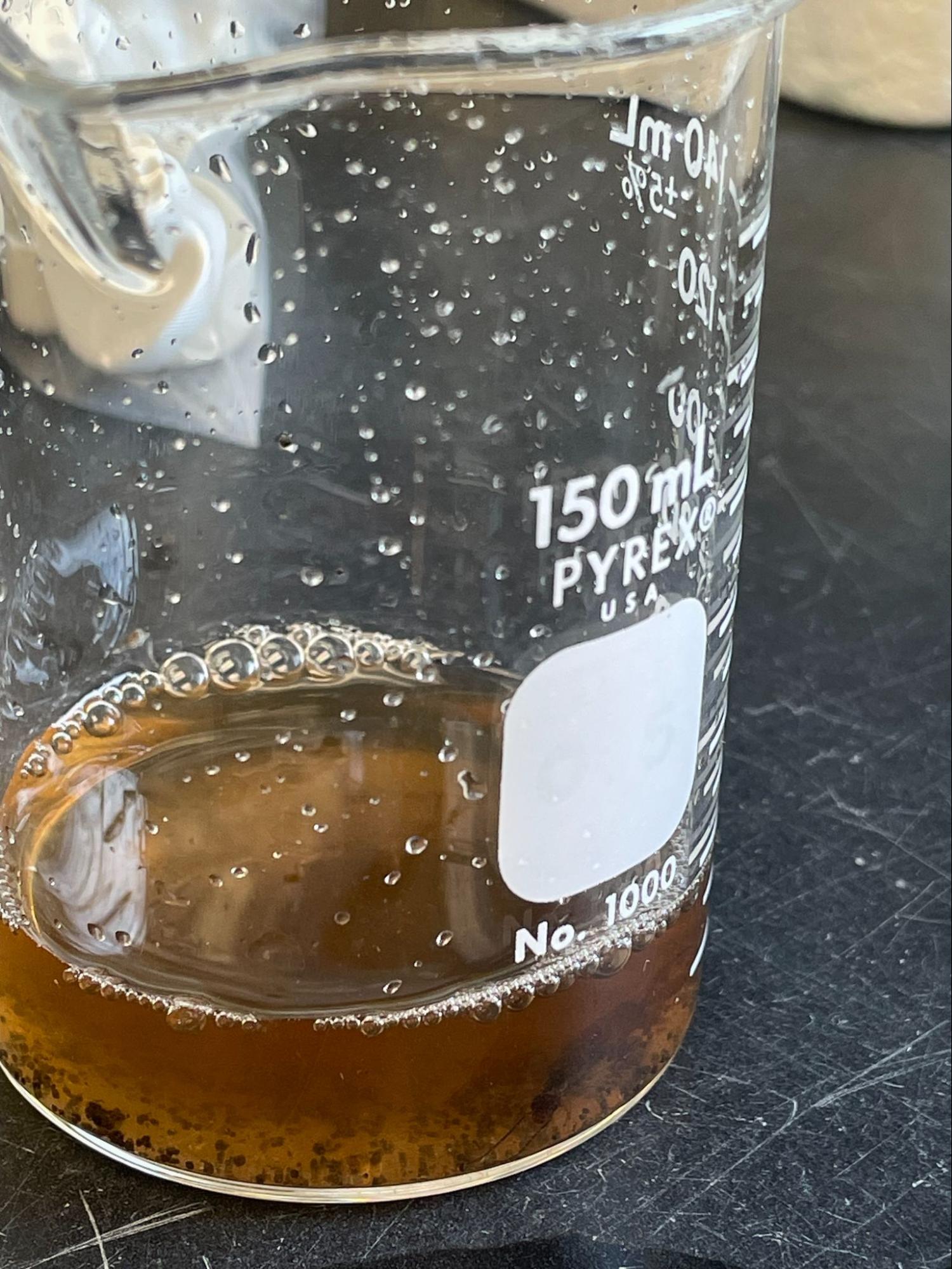

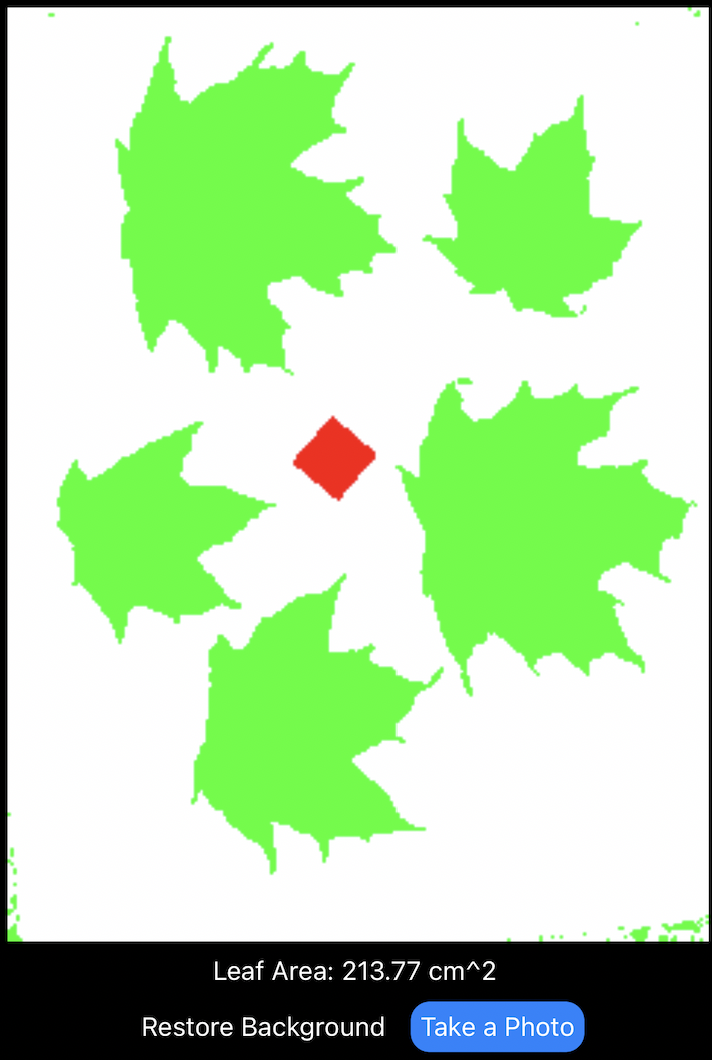

As a part of Frankie’s REU project, she researched and designed a protocol to process and measure dry deposition of heavy metals onto the surface of leaves across urban parks with different levels of industrial exposure. She had two foliar collections over the summer and experimented with a new foliar washing procedure in efforts to quantify the dry deposition of heavy metals on the surface of the leaves. To prepare the samples, Frankie had to calculate the total leaf surface area of each collection and wash each sample for 30 minutes with a 1% HNO3 solution for ICP analysis. Her sampling efforts will help reveal how heavy metal exposure varies across the city, with important implications for the urban ecosystem and humans alike.