This post is part of the LTER’s Short Stories About Long-Term Research (SSALTER) Blog, a graduate student driven blog about research, life in the field, and more. For more information, including submission guidelines, see lternet.edu/SSALTER

by Abigail Borgmeier, PhD candidate at Brigham Young University

I can’t go a day without a colleague responding to the question of how they’re doing with “fine given…the circumstances” while they wave vaguely at the world at large. Our circumstances have changed a lot in the last six months, leaving many US scientists feeling uncertain about the future. But the practice of addressing and reacting to the new challenges is something ecologists are very used to.

Challenges in the field, before you even get to the field

Roadblocks aren’t anything new to scientists doing research in remote locations. We at the McMurdo Dry Valleys LTER site are super lucky to have the science support provided by McMurdo Station just outside of the Dry Valleys of Antarctica. McMurdo Station provides the expertise of lab managers, helicopter pilots, waste management technicians, and so many more who make the science possible. Despite all these resources, that help isn’t guaranteed. From reduced helicopter hours, packed field camps, to less space for scientists on station, there are plenty of challenges that have nothing to do with the science itself. The way we overcome these challenges is by leaning on a network of people who all have the same goal, but a diverse range of skill sets and experiences.

There are a lot of roadblocks from D.C. to the Dry Valleys and everywhere in between. What we’ve learned is that it’s never the time to throw in the towel. Sometimes, we all need to dig in our heels and keep doing what we do best—good science.

Try to mirror ecosystem resiliency

Ecosystems are more resilient to disturbance when there is a larger interconnected web of creatures, each contributing their part. Creatures that live in harsh environments, such as the Dry Valleys of Antarctica are optimized to make do without. Freezing temperatures? Nematodes produce antifreeze proteins. No water? Algae can nearly completely dry out and go dormant. No light? Organisms in permanently ice-covered lakes can scavenge other nutrients instead of getting their energy from light. The environment demonstrates the creativity and diversity that we need to build resiliency within our scientific community, especially under harsh conditions.

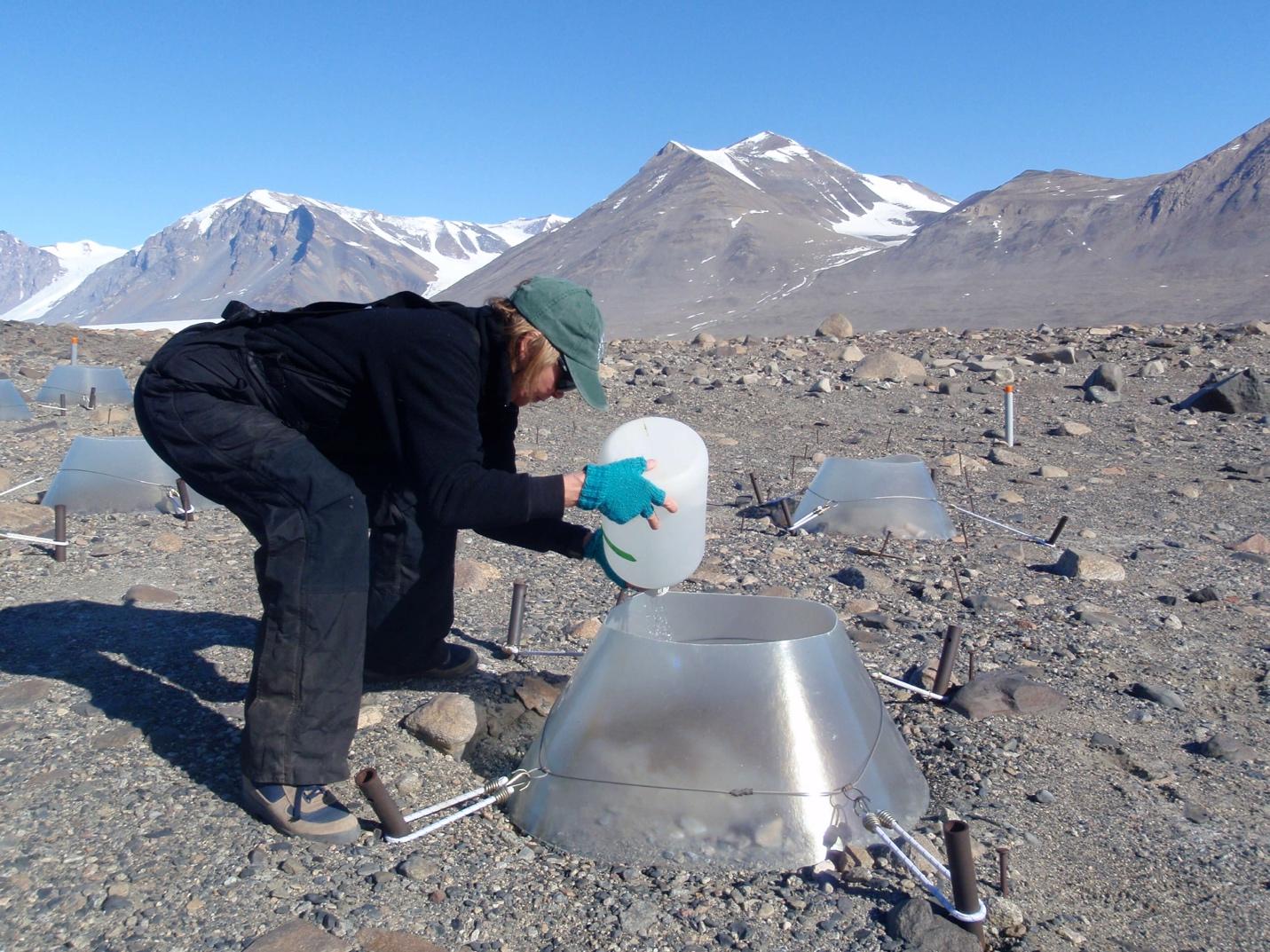

Ecology research is expert at making the most out of slim resources. I love hearing stories from other researchers about the amount of duct tape that holds their experiments together. Inventive and resourceful experimental design brings about some of the best science. Polar science is facing diminishing resources in the coming years. We are all going to have to be more creative, collaborative, and flexible in our science, but that doesn’t mean that great science is going to stop happening. The ingenuity of the people that we work with is a resource that is only growing. And these are the people we lean on in the field when the going gets tough.

Credit: Byron Adams, CC BY-SA 4.0.

Supported and inspired by scientific legacy

Organisms in the Dry Valleys have gained traits which give them this resilience after surviving in an incredibly dry, cold, and extreme environment over millions of years. Scientists haven’t been working in Antarctica for that long, but we have built up an impressive legacy of resilient scientists who inspire early-career researchers. One of my favorite examples is the late Dr. Diana Wall, one of the first scientists to study soil fauna in the Dry Valleys of Antarctica. She overcame numerous challenges, such as developing new field protocols to conduct experiments in this remote location and established the McMurdo LTER to ensure future studies were possible. In a 2023 interview, Dr. Wall said, “perseverance is a good thing… make sure to keep at it. There’s still lots to learn, and the more we know, the better the predictions will be.” (https://usscar.org/us-antarctic-interview-series/diana-wall).

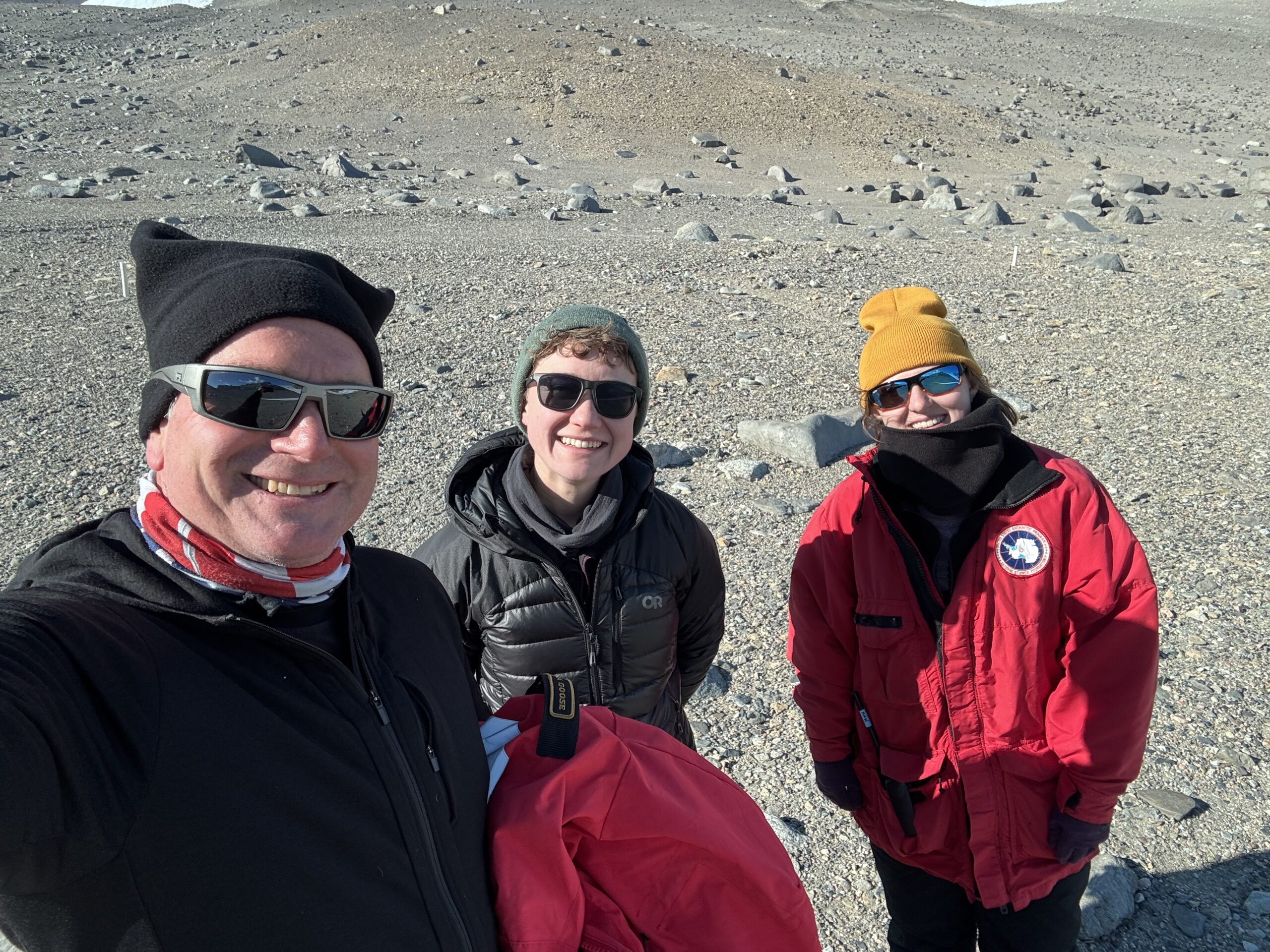

Credit: Byron Adams, CC BY-SA 4.0.

The only non-diminishing resources

I have been finding it hard not to get discouraged, to spiral into despair. Let the resiliency seen in the natural world be your call to action. To keep doing your science, supporting your students, reaching out to colleagues. Maybe our environmental legacy as ecologists is to refuse to give up or give in, much like the organisms we study. Especially now, we need to lean into our human networks, our human resources and find that resiliency within our community.

Credit: photo credit: Dr. Byron Adams

Abigail is a PhD candidate at Brigham Young University, advised by Dr. Byron Adams. She studies nematode ecology and evolution in the Dry Valleys of Antarctica and the Sevilleta desert in New Mexico.