This post is part of the LTER’s Short Stories About Long-Term Research (SSALTER) Blog, a graduate student driven blog about research, life in the field, and more. For more information, including submission guidelines, see lternet.edu/SSALTER

by Paige Kleindl, graduate student at the Florida Coastal Everglades LTER

From Art Jams to Gallery Shows

Three years ago, during Covid, I began my PhD at Florida International University, participating in the Florida Coastal Everglades Long Term Ecological Research (FCE-LTER) program. A few FCE graduate students were in my Covid social bubble, and we discovered we all had a passion for creative and artistic pursuits. We began to gather, turn on tunes, break out the pencils and brushes, and make art, often related to our environmental research experiences. Over time, these ‘Art Jams’ widened my circle and opened my eyes to the accomplished creatives who were hidden within talented ecologists, biogeochemists, and taxonomists.

Our shared love for this art-science crossover led us to host a successful FCE LTER photo competition at a local brewery, featuring images of our beloved Everglades. This got me thinking: If I can share photography with the community, why can’t I share the paintings I had made of my study species? The first FCE LTER Art Showcase was birthed six months later in the same brewery back room. Among the artists and art-appreciators milling about the exhibit space, the FCE outreach coordinator, Nick Ohem, approached me with a side eye and raised eyebrow. He upped the stakes. “I’ll put you in contact with Bryan, he is the curator for Florida International University’s art gallery in the Glen Hubert Library.”

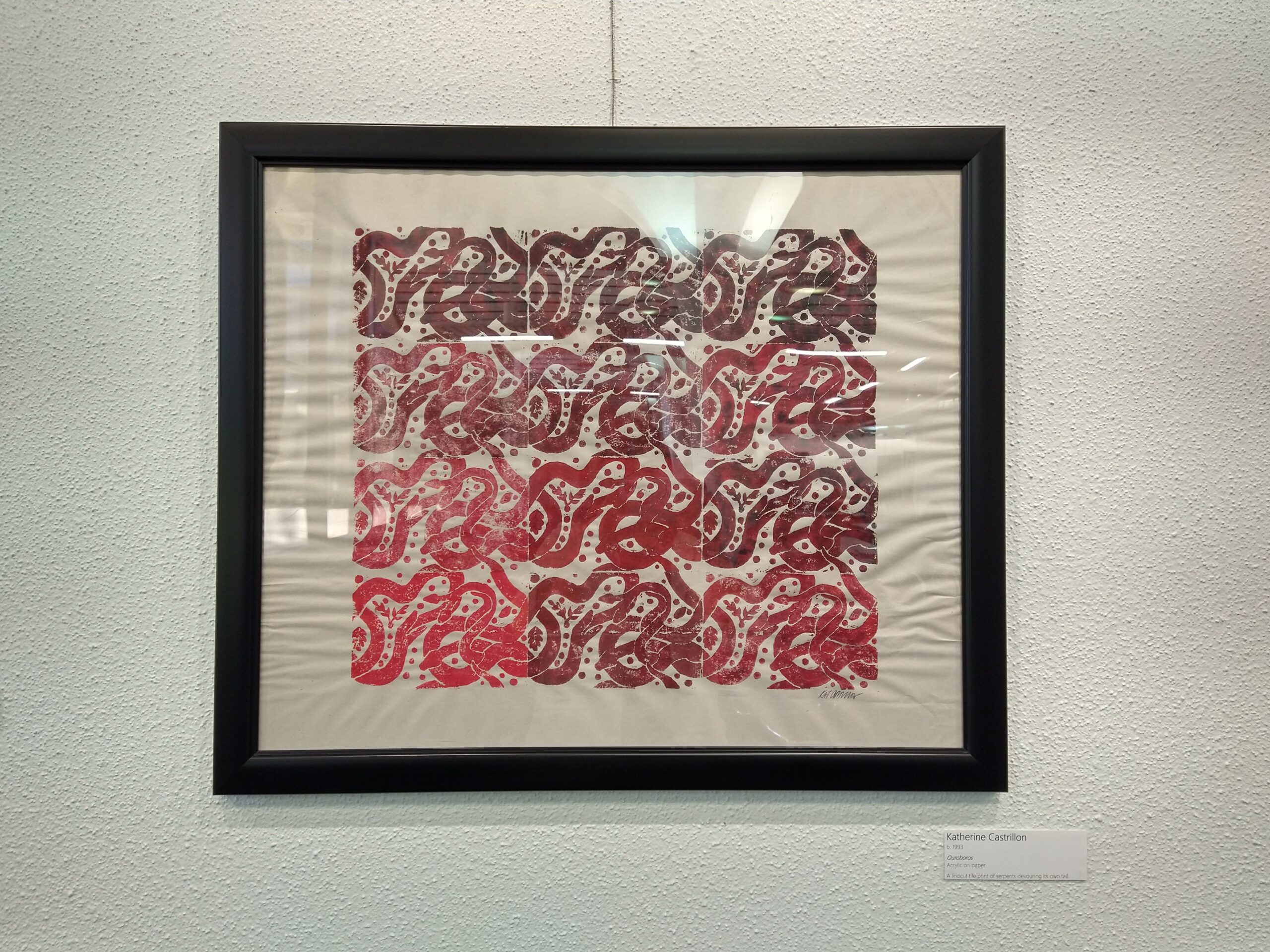

Art pieces created by Katherine Castrillon (left) and Joshua Linenfelser (right).

A year later, I find myself admiring the framed works of eleven artists who are also FCE scientists, which fill the walls surrounding studying students. Over 50 art pieces line the first and second floor walls of the library. I tour the exhibit and take in my friends’ creative accomplishments; a red monochrome linoleum print of intertwined and connected snakes, aerial images of detrital discharge into Florida Bay, embroidery of microscopic diatoms, a life-like sketch of an alligator, an up-close and colorful illustration of a dragonfly face, and a botanical cyanotype print collaboratively created by FCE students to depict typical natural finds on a hike through our ecosystem.

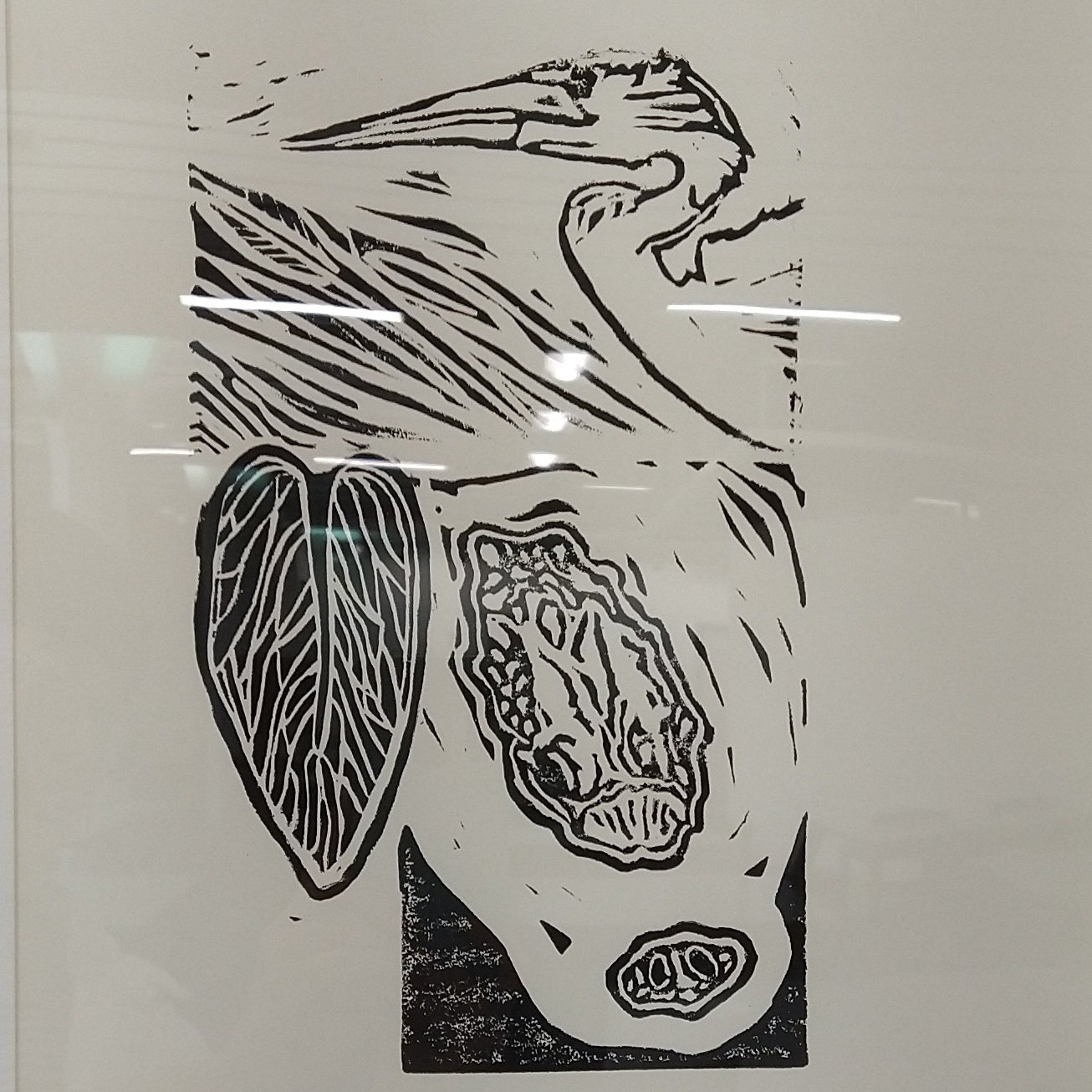

Art pieces by Hanna Innocent (left) and Franco Tobias (right).

Many Perspectives

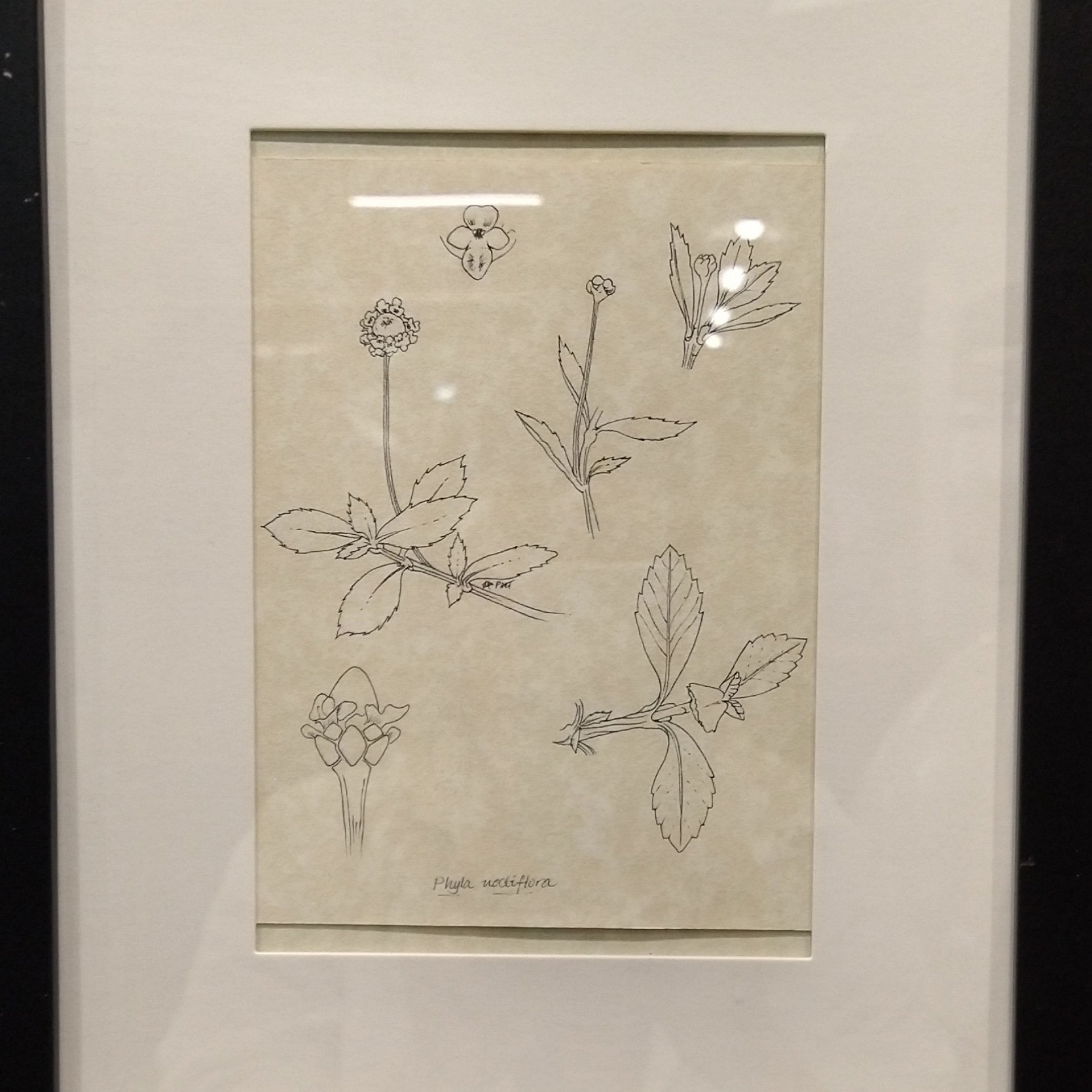

I curated the exhibit to guide the audience’s walk through of Everglades’ views from different lenses. Animal and plant drawings occupy the first floor. Black and white illustrations of plants guide the onlooker’s eyes to the morphological differences between species, while flowers on display across the room highlight the specks of color found few and far between the stems and leaves of grasses and sedges in the Everglades. Surprisingly, only a few animal portraits were created using color, which is likely a product of artist preference.

Color knows no limit on the second floor. One wall is dedicated to my favorite bioindicators – diatoms. Although diatoms are naturally limited to an iridescent shine and brownish-yellow pigments in live samples, artists (myself and Hanna, another member of my lab) opted to incorporate vibrant hues in our depictions of these taxa. The last wall is dedicated to photography that provides snapshots of the coastal wetland, with images ordered along a scaling gradient. Arial photography leads the line of pictures which ends with macro-photography of sawgrass blades, flower stamens, and apple snail eggs. No matter the art medium, each art piece captures a different angle of our study system and culminates into a cohesive and comprehensive showcase of the Everglades.

Art pieces by Michelle Yi (left) and a collaborative cyanotype by FCE LTER students (right)

More than a Scientist

I titled the exhibit ‘More Than a Scientist’ to bring light to the multifaceted nature of the individuals who, at first glance, in their waders and sun-bleached hats, the world would not label as artists. These people, my friends, combine their intrigue and appreciation for the environment, organisms, and processes they study with their passion and drive to capture glimmers of the Everglades in a way that speaks to them.

We choose to create and fixate on things we find beautiful, interesting, or odd, and how lucky we are to also explore these phenomena every day. Professionally, Tommy is a Ph.D. candidate that studies the resilience of diatom metacommunities facing a shifting hydrologic landscape due to saltwater intrusion and water management. He earmarked funding in a research grant to purchase a waterproof camera to document algal growth; now he spends his weekend runs through the Everglades capturing the miniscule details of plants and animals that only a microbiologist could spot.

FCE LTER Graduate Student Tommy Shannon and one of his photos.

Carlos, another Ph.D. student, is often found in the field surveying macrophyte communities to unravel how their morphologic traits reflect Everglades’ management efforts. In his free time, he has learned how to carve linoleum pads into herons, alligators, and leaves for prints I see displayed on the wall today.

Carlos Pulido and one of his linoleum prints.

Franco is a lab manager and diatom taxonomist of 25 years who makes tromping through sole sucking mud look easy. Not only does he capture brilliant photos of the early morning landscape and couple them with poetry, but his steady hand also creates brilliant graphite replicates of botanicals, bees, and birds.

Franco Tobias and one of his botanical illustrations.

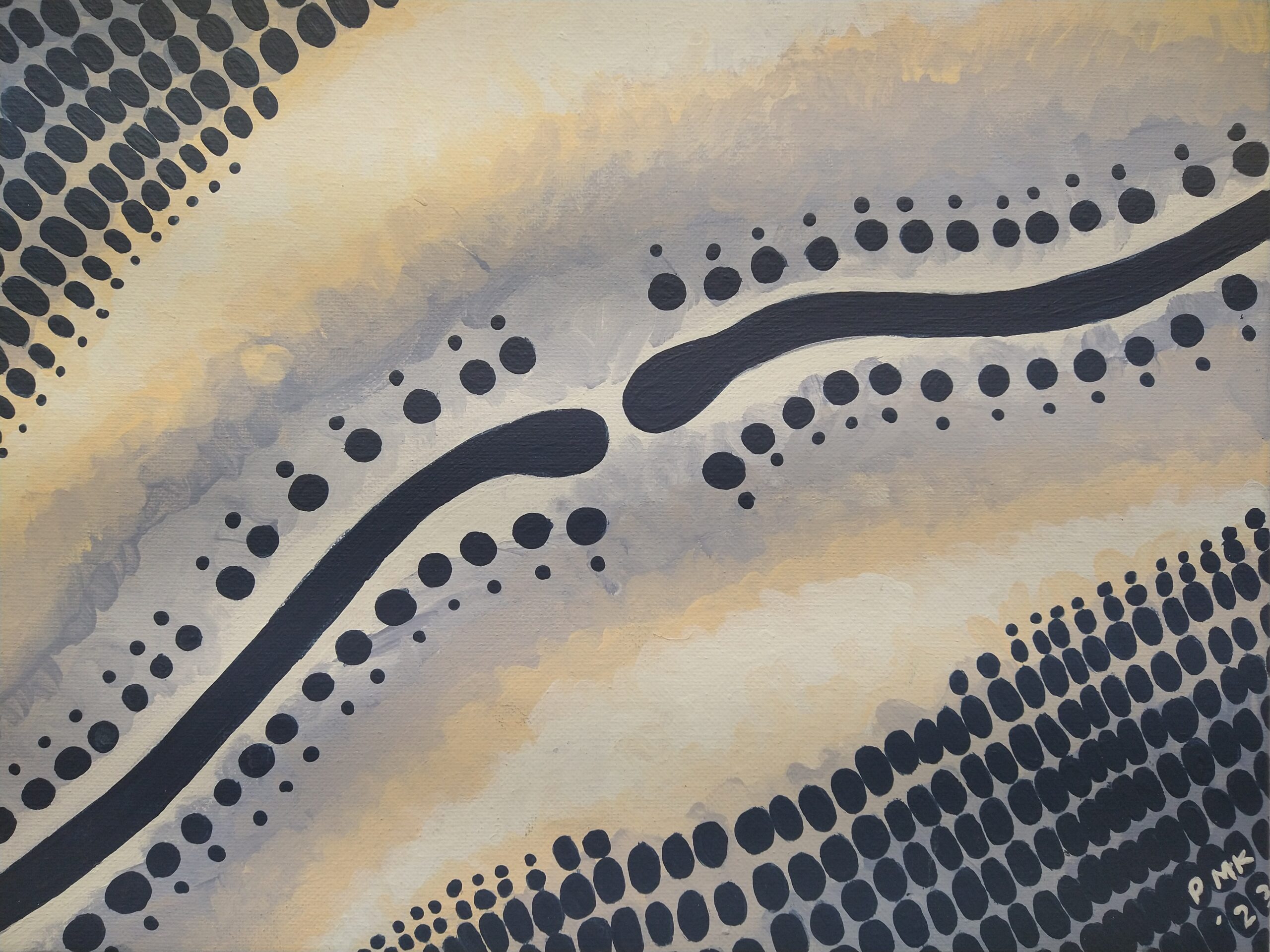

My own art ventures from realism as I use the shapes present in diatom morphology to create colorful and abstract paintings of the organisms I have been getting to know the past 10 years. Designing this art exhibit gave me motivation to create art inspired by my Ph.D. work investigating the interactions between macrophyte and microbial mat communities along hydrologic and phosphorus gradients in the Everglades.

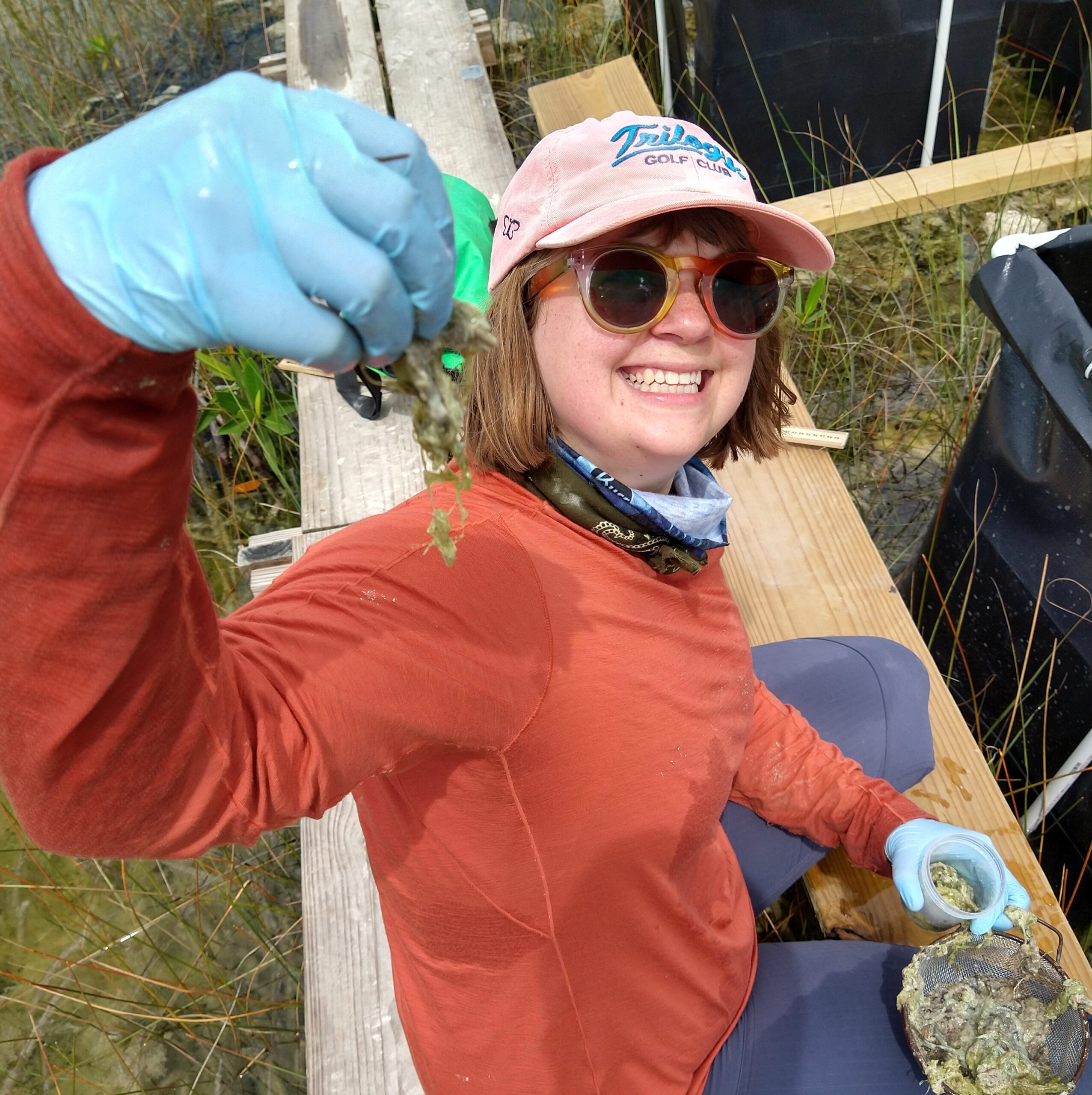

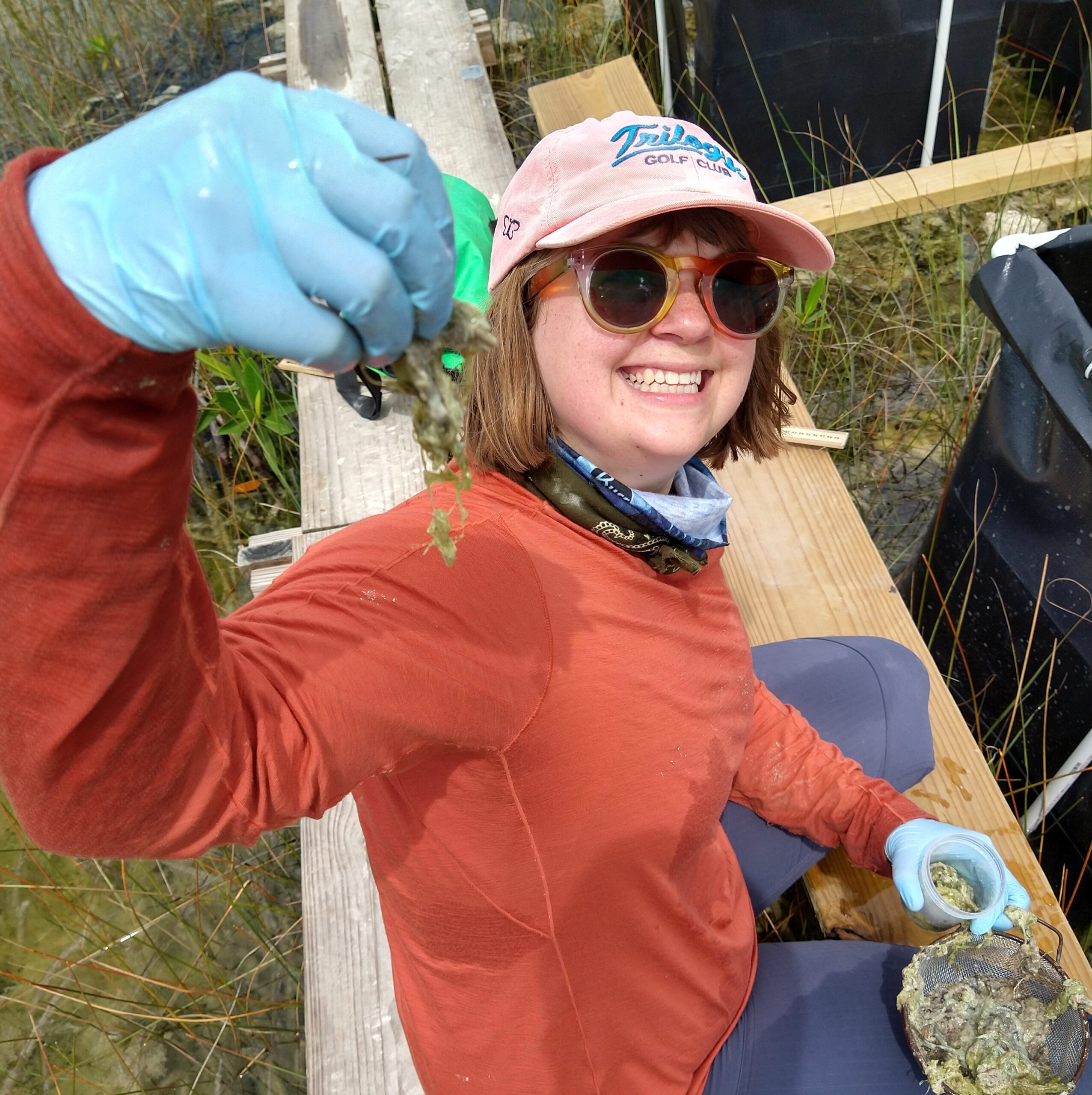

Paige Kleindl and one of her paintings.

Fostering connection

It has been my honor to share these professional works with the broader community and an even greater blessing to see the pride, excitement, and accomplishment manifesting as bright eyes and smiles on the faces of my friends as they share their creative thought processes with an engaged audience. Their art portrays not only the Everglades, but also the passion, curiosity, and perspective of each artist. It connects us to our study system in a way that peer-reviewed journal articles, statistical significance, and scientific conferences may not.

Left: Artist Michelle Yi next to her art pieces. Middle: FCE LTER members contemplating and discussing what they see at the exhibition opening. Right: FCE artists Rosario Vidales, Nicki Chlebek, Paige Kleindl, Tommy Shannon, and Franco Tobias.

Art commands an emotional response not captured in jargon or graphs, sparks conversations not commonly heard in labs, and invites in the voices and opinions from those who do not conduct ecological research. Although the spheres of art and science may seem separate at times, the heart of both disciplines is rooted in individuals observing an object or process and being compelled to interpret it into something meaningful. One can help the other; my knowledge of diatom morphology informs my artistic process and my manipulation of diatom shapes depicted with color has deepened my comprehension of their symmetry, intricacy, and differences among genera. I know my experience growing simultaneously in both disciplines echoes the stories my fellow FCE LTER researchers share as I hear them testify to others at our gallery opening.

From my experience, art and science are pleading to integrate but require a space and community to do so. Integration is already quite common in the scientific field but is shared in less obvious contexts than a spelled-out science meets art exhibition such as graphical abstracts, food web figures, and field photography in conference posters and PowerPoints. Images of my diatom art have begun showing face in my professional presentations, and I hope to spot a plethora of artistic mediums popping up in the dissemination of other scientists’ research as well. I hope that environmental artists are more freuquently invited into conversations about the management of their local ecosystems and are asked to lead workshops on how scientists can better communicate complex processes to the public. Awareness of others’ talents lead to the formation of this successful exhibit, and I hope it will inspire future collaborations between career artists and scientists for the FCE and other LTERs. The fruits of this exhibit have only just begun growing. I encourage all of the artists hidden amongst the scientists to step forward and share your creative passion with others at your site—you never know what may happen!

Paige Kleindl is a Ph.D. candidate at Florida International University in Dr. Evelyn Gaiser’s lab, where she has been involved in FCE LTER research for the past four years. Her dissertation research focuses on how macrophyte and benthic microbial mat community interactions change along hydrologic and nutrient resource gradients in the Everglade. She is particularly interested in the importance of environmental vs. biological variables in driving macrophyte and mat community shifts at different spatial scales. Outside of facilitating a space for art and science integration, she enjoys watering her plants and playing the drums.