This post is part of the LTER’s Short Stories About Long-Term Research (SSALTER) Blog, a graduate student driven blog about research, life in the field, and more. For more information, including submission guidelines, see lternet.edu/SSALTER

by Emily Reynebeau

The beautiful thing about working in Antarctica is that the entire continent is dedicated to science. Among the numerous research groups in Antarctica, one of the longest standing is the McMurdo Dry Valleys LTER.

Located along the Eastern coast, the McMurdo Dry Valleys are the largest ice-free region on the continent. The valleys are an expansive exposed soil-and-rock landscape, surrounded by glaciers, which melt into streams that feed into lakes which are permanently covered by ice. Taylor Valley, our main area of study, is landmarked by three distinct basins, named for the dominant lake in the center (Lakes Fryxell, Hoare, and Bonney) each covered in 2 to 5 meters of ice above 15 to 50 meters of liquid water.

Credit: Emily Reynebeau, CC BY-SA 4.0.

The permanent lake ice protects the water column from air turbulence and aeolian input, resulting in an intense stratification with physical and chemically distinct layers. Water samples are collected by field crew, colloquially called “Limno Team”, in Nalgene sample bottles at discrete depths, and the water is analyzed for a suit of physical, chemical, and biological parameters two to three times a year.

However, the cost of doing this science, or any science really, can often feel like a drain on resources. In accordance with the Antarctic Treaty, all waste produced on-continent must be shipped back to the researcher group’s home-country, further highlighting the resource impact. Because of this, the MCM-LTER, and the newly formed Sustainability Committee, has taken steps to help reduce our carbon footprint.

Shake-Shake-Dump, Repeat

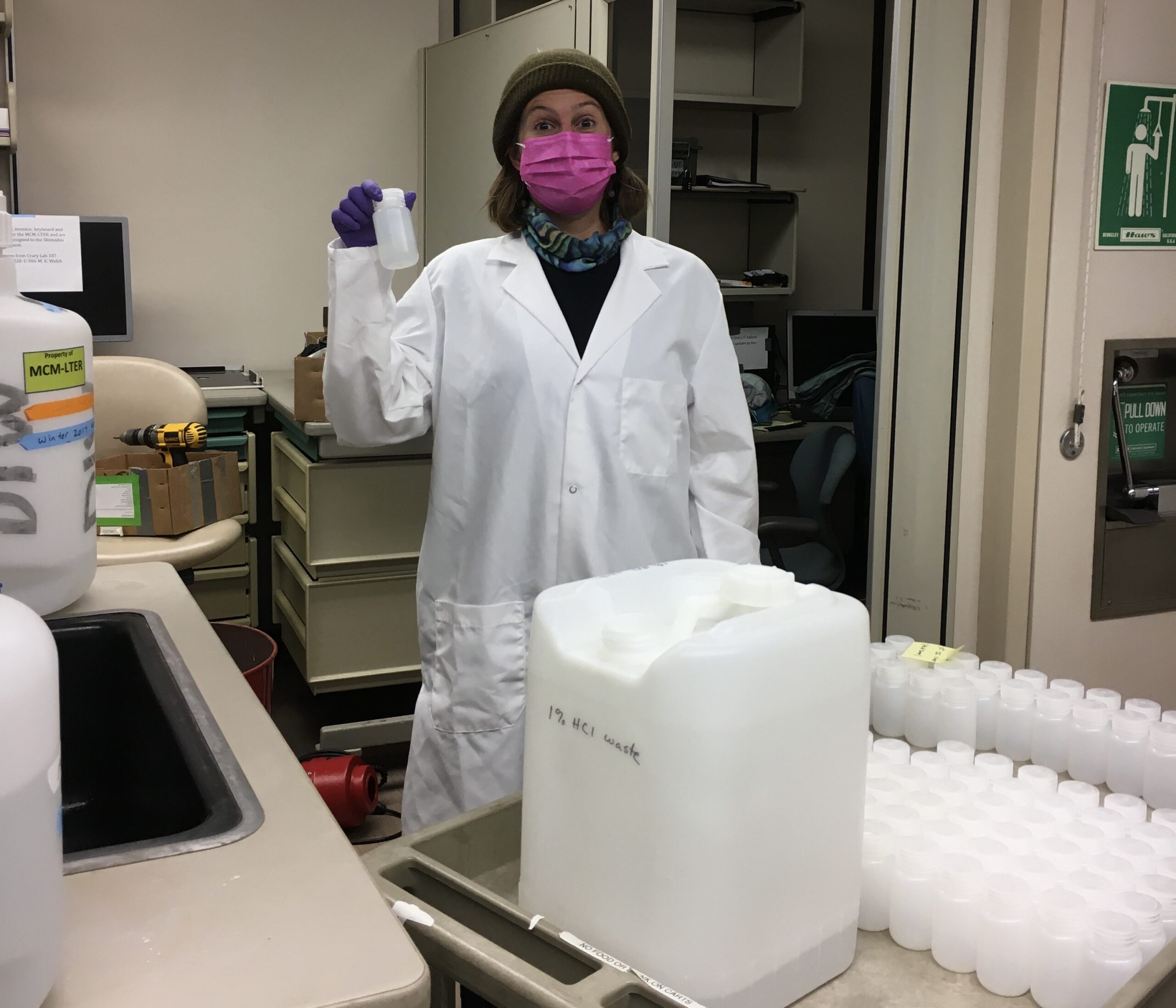

We prepare for our field excursions for about two weeks in McMurdo Station before heading out to the Dry Valleys field camps. Sample-bottle-washing has become an entity of its own, an endlessly tedious affair with the almost affectionate catchphrase, “shake-shake-dump”, referring to the physical act of filling a Nalgene sample bottle with acid or water, shaking twice, and dumping out. And where it is dumped out is crucial; One learns very quickly that the waste stream in Antarctica is extremely important.

Credit: Emily Reynebeau, CC BY-SA 4.0.

When acid-washing a bottle, it must be washed first with acid and dumped into a separate acid waste vessel, followed by water rinses emptied into the sink. Accidentally dumping a small volume of acid (pH 2) will set off downstream alarms of pH imbalance within the laboratory facility wastewater tank, eventually destined for the station-wide wastewater facility, which in turn cleans the water before returning to the ocean. Awareness during this seemingly mundane activity is pertinent.

For years, we have used a 50L carboys for acid waste; with awareness and when done properly, one might notice how quickly a waste vessel is filled. In 2021, we learned the fate of our acid waste. An employee in Waste Management informed us that when we requested acid waste disposal, our 50L acid waste carboys were being collected from the laboratory, brought to the Waste Management Facility, emptied into a 50-gallon drum, and both the drum of acid and the EMPTY plastic carboys were being shipped home for disposal. This was an absolutely shocking revelation: Entire boxes of empty plastic carboys, destined for the landfill. We acted fast. After only a few short emails, we quickly realized that we could work with the waste management folks to reobtain the 50L plastic carboys for reuse, and help to decrease our waste footprint. An easy victory that has already made a significant impact on our plastic waste was built by simply communicating.

Clean and Green

Field crews must be outfitted with appropriate gear to weather the balmy -10°C summer nights. A tent large enough to comfortably fit a sub-zero sleeping ensemble and durable enough to withstand 40+ knot winds is almost cozy. The privacy of a solo tent is highly prized after long days working with your team in the shared lab spaces, shared lake ice shelters, and cooking together in the shared living-space hut.

Credit: Emily Reynebeau, CC BY-SA 4.0.

The communal living has given participants a chance to consider not only the impact of doing Antarctic science on global resources, but the environmental cost of simply being alive between working hours. Water needs are met by obtaining ice chipped from the frozen lake or carried back to camp from nearby calving glaciers, and passively melted by bringing into the hut and letting sit atop a diesel-fueled Kuma stove. Passive melting, while more efficient, is a slow process, and requires full participation by all field crew members to maintain a supply before liquid water runs out. And run out it does; Water obtained by this method is used for all household purposes. Supply must support drinking water, cooking, washing hands, washing dishes, and brushing teeth.

Hygiene is not taken lightly, especially in the field camps. Failure to properly and often wash hands or work spaces opens the small and intimate residents of a field camp to a range of infections, often generically referred to on-continent as “the crud”. With only a tent to recover in, it is often better to mitigate rather than treat. However, frequent hand washing leads to increased gray water and landfill bulk, in the form of paper towels, a hygienic option in this isolated world without laundry. Recognizing this unavoidable issue and the cost of maintaining a healthy environment, individuals have started bringing a personal hand towel from home to be used in the field camps. While a single towel for a group of potentially 10 field crew members would quickly be unusable, a solution to the paper towel waste problem is easily met by encouraging each individual to be responsible for their own private towel. Disseminating this information to first-time field crew members has sparked this act as common practice, and has now significantly decreased the volume of paper towel waste shipped back to the US.

With each season, we make small changes, both in our work and personal lives. Small changes are passed to the next generation field crew, and eventually form long-lasting cultural habits. The next gen can then see what we did not see and make new changes. In this way, we continue to make things more perfect.

Credit: Emily Reynebeau, CC BY-SA 4.0.

Emily Reynebeau has been at the McMurdo LTER since 2018, first as a Master’s student and now a PhD student at the University of New Mexico, and has gone down to the Dry Valleys four times. When she’s home, she loves hanging out with her husband and their three dogs.