Credit: Credit: MCR-LTER CC BY-SA 4.0

LTER sites are both physical places and communities of researchers. Some of the physical places are remote or protected from development, others are deliberately located in cities or agricultural areas. Either way, the program of research for each LTER is tailored to the most pressing and promising questions for that location and the program of research determines the group of researchers with the skills and interests to pursue those questions.

While each LTER site has a unique situation—with different organizational partners and different scientific challenges—the members of the Network apply several common approaches to understanding long-term ecological phenomena.

Observation

Every site maintains a group of core data sets, often with decades of repeated observations of key variables for their site. The core themes offer general guidance for selecting these measures, but local knowledge drives the selection of specific variables. So, permafrost depth may be a core data set for the Arctic LTER, where it determines active soil depth, but irrelevant for a desert or ocean LTER. Neighborhood income or education level might be critical for an urban LTER, but pointless for an LTER in a remote forest.

Credit: Credit: CDR-LTER

These long-term data sets are freely available to all. Researchers and students inside and outside of the LTER network use them for context to help interpret shorter-term studies, or discern trends over time, for model calibration and testing, or for comparison with similar measures at other sites.

Core data sets are available through the Environmental Data Initiative repository or searchable through the DataONE framework, but the best source of information about which datasets are considered core at each site is the site’s data catalog. Links to each site’s data catalog are provided on the site profile pages.

Experiments

The stability provided by predictable long-term funding allows LTER sites to develop controlled experiments at the ecosystem scale with the expectation that treatments can be maintained for the foreseeable future. LTERs have established and continue to maintain some of the seminal experiments in ecology, with dozens—even hundreds—of novel findings that could not have been advanced or tested in other ways. Classic experiments include watershed manipulations at Hubbard Brook, biodiversity experiments at Cedar Creek and elsewhere, soil warming plots at Harvard Forest, long-term decomposition experiments at Andrews Forest, nutrient addition experiments at Toolik Lake, and many others.

Credit: U.S. Forest Service Northern Research Station

New experiments continue to be developed all the time. Recent additions include seawater addition experiments at Georgia Coastal Ecosystems LTER and ice storm experiments at Hubbard Brook LTER. Maintaining these experiments is a service to ecological researchers of today and tomorrow. LTER and non-LTER researchers may request access to experimental plots and collected samples. And in the case of slowly changing pools or legacy effects, the changes wrought by experimental treatments may only become apparent 20, 30, or 50 years down the road.

A more recent phenomenon in ecology is the growth of distributed experiments such as NutNet, DroughtNet, ITEX, or LIDET in which a similar (often low cost) experimental model is deployed in different ecosystems to provide comparable data on how ecosystem conditions change the impacts of a given disturbance. Many of these experimental networks grew out of—or were inspired by—cross-site LTER experiments.

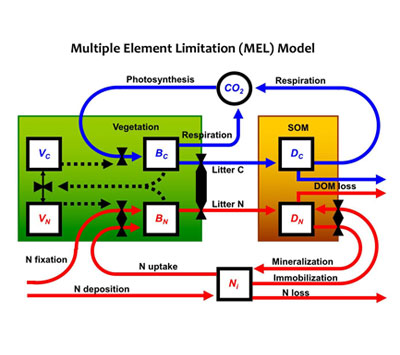

Modeling

Credit: Ed Rastetter

A major component of every LTER proposal is a conceptual model that incorporates hypotheses about the major drivers and feedbacks on ecosystem functioning for that system. As an LTER project matures, those models become more detailed. Some hypotheses are rejected, others confirmed and elaborated. Over time, many teams find that computational models are the clearest way to articulate their evolving understanding of the connections in their system. Comparing the models’ predictions to the measured results of experiments and long term observations offers a way to test the understanding that they represent and probe for weaknesses.

The long-term data sets maintained by LTER sites are also an invaluable resource for calibrating and testing ecological models developed by other researchers.

Predictive Models and Scenarios

Because of their longevity, many LTER sites have strong relationships with resource managers, government, and non-governmental organizations in their communities. This situates them to act as honest brokers in developing scenarios, the plausible future trajectories that often underlie predictive models.

Synthesis Science

With dozens of research programs collecting long-term data in five major areas of inquiry, opportunities for comparative studies abound. From very early in its history, the LTER Network included explicitly-funded data managers, who attend to quality control, curation, and archiving of the huge variety of data produced by LTER investigators, collaborators, and students.

Those data are publicly available through the Environmental Data Initiative and searchable on DataONE—and have inspired and launched many major ecological syntheses efforts. In recent years, the Network is focusing additional attention on making LTER Network data fully and easily comparable, via synthesis working groups and efforts such as Community Responses to Resource Experiments (CORRE).

But LTER synthesis efforts are not limited to those driven by easily comparable data. Drawing connections across ecosystems types, such as the comparison of abrupt shifts in ecosystem regimes produced by investigators from desert, marine, antarctic and coral reef ecosystems (Bestelmeyer et al. 2011) would be hard to achieve in more homogenous Networks.

Find more information on current synthesis working groups and past working groups on the LTER web site. The Network Office issues regular calls for synthesis working group proposals, which are open to scientists from within and outside the LTER Network.

Partnerships

Whether the focus is site operations, scientific synthesis, education and outreach, or data management, the LTER Network builds on relationships to achieve more than could be accomplished alone. Virtually every LTER program works with an organizational partner to manage and maintain a functional, accessible research site.

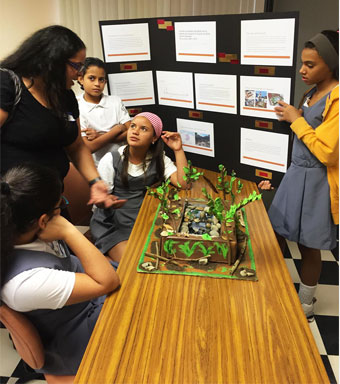

The LTER Network engages with other national and international networks, including International LTER, Critical Zone Observatories, National Ecological Observatory Network, Ameriflux, NutNet, DroughtNet, and many others to share data, theories, context, and perspectives. Education and outreach programs work with school districts, educators, and national STEM education organizations, such as Data Nuggets to improve and share educational resources. Data managers partner with Environmental Data Initiative, DataONE, Earth Science Information Partners, and publishers to optimize the data lifecycle and make LTER data more discoverable, accessible, and useable.

Do you think that your organization might find mutual benefit in partnering with LTER? Contact the LTER Network Office to explore the possibilities.