Credit: NGA LTER, CC BY-SA 4.0.

NGA’s Virtual Field Trip brings the Gulf of Alaska to the classroom, pairing a video, video game, and activities to immerse students near and far in the ecosystem.

The Northern Gulf of Alaska (NGA) LTER site is offshore and, primarily, underwater—meaning the vast majority of people will never see it in person. The NGA’s recently launched virtual field trip lets students near and far interact with the hard-to-reach site. After two years of concerted development, the field trip materials were released this winter, and teachers began using the curriculum this spring.

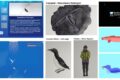

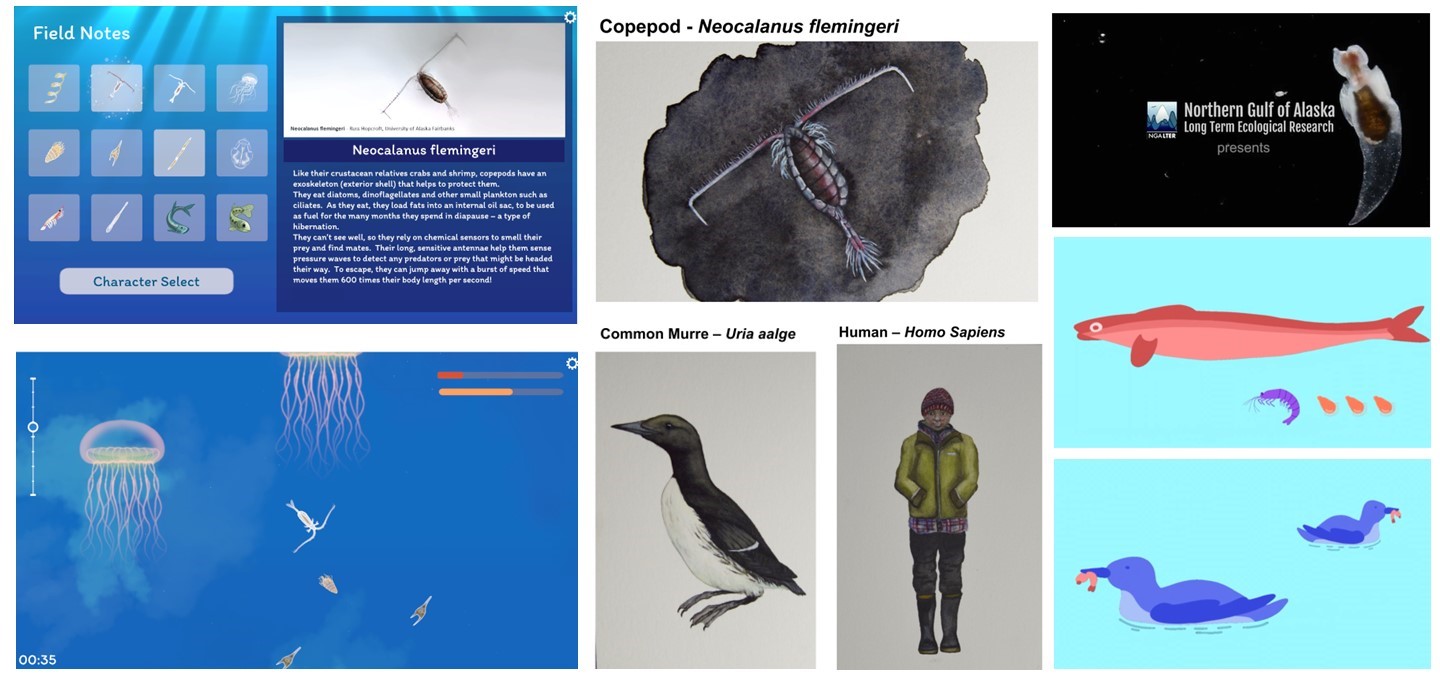

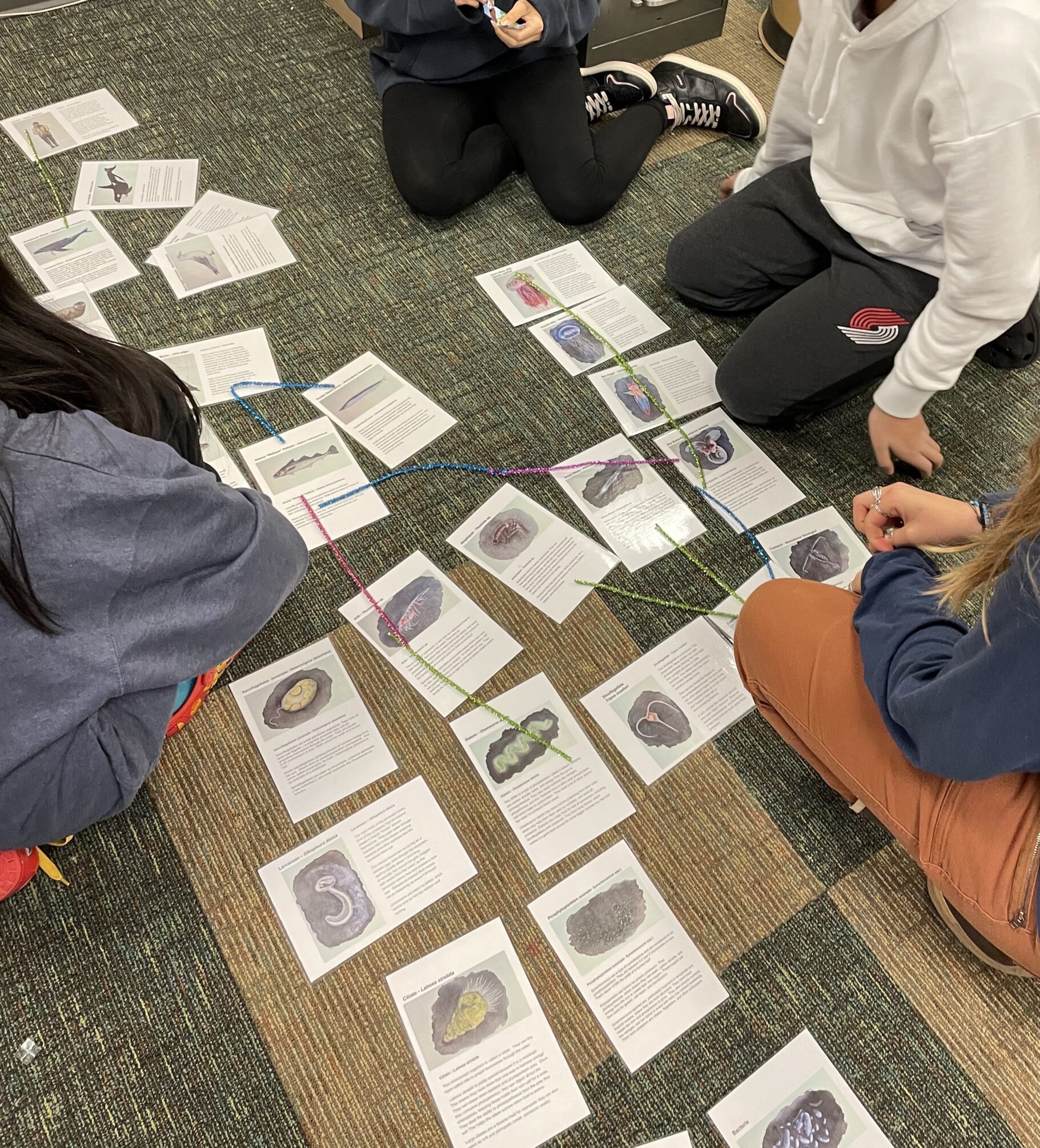

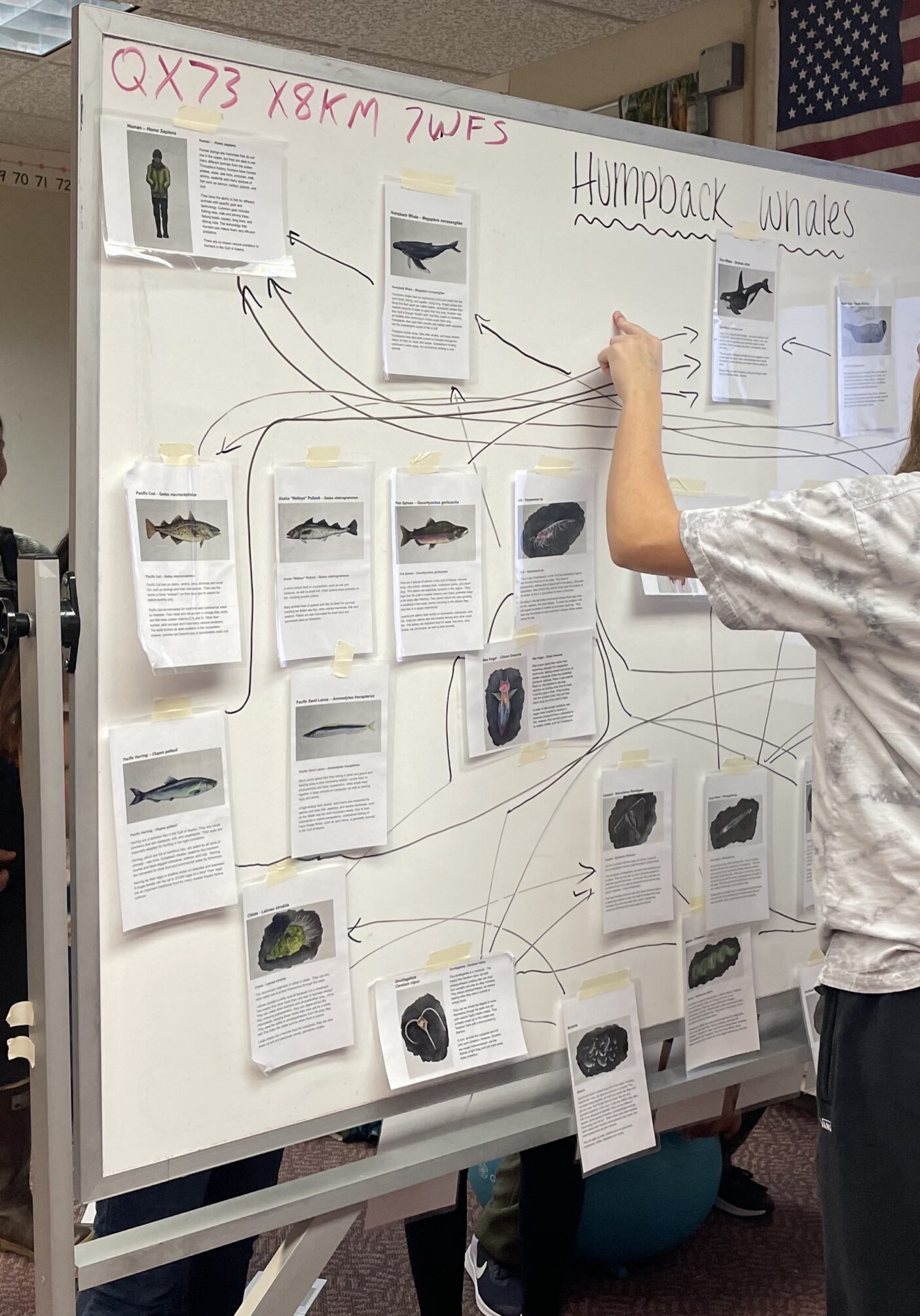

Centered on marine food webs in the Northern Gulf of Alaska, the field trip uses several different tools to teach students about ecology and science. A video game lets students immerse themselves in the Gulf of Alaska, thinking critically about their character’s role in the food web as they try and beat levels. A video created using footage of Gulf of Alaska creatures and landscapes pairs with animated scenes that reveal interactions within the food web. And, illustrated “creature cards” let students arrange their own food web in the classroom. Paired with accompanying curriculum developed for teachers, the field trip uses these tools to achieve science learning objectives set by the state of Alaska and supports age-specific reading and writing standards in the state.

Credit: NGA LTER, CC BY-SA 4.0.

Finding the edges of a food web

From the get go, the education team faced a central challenge: developing a curriculum that was scientifically accurate, but still digestible and relevant to their target audience: middle school students. To strike that balance, educators needed to work closely with researchers at the site. “I developed a really basic food web of the Northern Gulf of Alaska—it was a Google slide with all these lines connecting things,” recalls Katie Gavenus, Education Manager at the NGA. “And then I showed it to the researchers and they told me everything that was missing, which was dozens and dozens of things.”

Finding balance was key. “I would talk with the plankton folks or I would talk with the seabird folks,” Katie reflects, “and I would ask ‘Okay, which are the most important [organisms] and how are they connected?” Her original food web expanded, contracted, and morphed with each round of feedback. Their final food web had 30 organisms, enough to demonstrate key concepts such as redundancy, but not too many to overwhelm the students—or the educators, illustrators, and video game designers on the project.

What is a field trip without the field?

The flagship of the Northern Gulf of Alaska LTER’s virtual field trip is their Food Web Video Game, a multi-level saga where players try to survive as organisms in NGA’s marine ecosystem. The game is gorgeous, (aquarelle marine landscapes sparkle and spin, playful critters bounce and flutter), and surprisingly difficult—it took me several tries to beat the last level, my character a ghost white crystal jelly.

Credit: NGA LTER, CC BY-SA 4.0.

During early development of the virtual field trip, Gavenus and her co-lead, educator and multi-media specialist Michele Hoffman Trotter, knew that the virtual field trip was missing something crucial: interactivity akin to being in the field. Michele suggested developing a video game.

The idea had merit: in a video game, students could embody an organism in the food web, dodging predators and eating to survive, immersed in the virtual Gulf of Alaska sea. But neither Katie nor Michele had developed a video game before.

“We really spend a lot of time thinking about how to fine tune it so that it would be increasingly difficult, but not too easy at the beginning, not too hard at the end, and fairly accurate ecologically,” says Katie. This took a lot of back-and-forth between the NGA science team, composed of researchers from the site, the video game developers, and Katie and Michele. “And so that balance of making the game fun, making the game educational and making the game accurate took a lot of iterations.”

As science educators, the team was set on making the video game as representative of real life as possible. “There are some things that we ended up putting a ton of time and effort into, like how the tail of an organism would move,” reflects Katie. After a particularly intense design meeting over one creature’s details, the team “all kind of forgot that as a background creature at scale with the [main character], [the background creature] is about this big,” remembers Katie, her fingers pinched to demonstrate the tiny scale of the organism. “There were definitely some times where we had to say, okay, yes, we could get into the minutia of this, but let’s step back a little bit and remember the overall learning goals.”

The results speak for themselves. Katie says when they introduced the video game into the classroom, “it was a huge hit. Kids were talking about the different shapes of the copepods and about how they moved. It’s something they learned from the game.” Katie and her team were thrilled. “We spent a ton of time on trying to make sure the antenna movement of the copepods was accurate. We felt sort of silly spending that much time on it!” But once they saw the students pick up on the same details, the time spent seemed worth it.

Sketching a broader ecosystem

Where the video game provided a hands-on experience with just a few select organisms, the rest of the virtual field trip covers an expanded food web. A short video featuring real footage of the Alaskan ocean and of creatures themselves allow students to see what the landscape looks like in real life. And the footage is interspersed with animation, playfully walking students through the food web. As soon as one animated creature’s description ends, it’s eaten by a larger predator on screen, which becomes the focus of the next section.

Similarly, the team developed “creature cards” that feature illustrations of each organism in the food web, plus a description of the creature. In the classroom, students can arrange these cards into their own version of the food web.

Bringing a media specialist onboard was key to developing all three activities. Hoffman-Trotter, a lecturer at several universities in the Chicago area, brought teams of her highly qualified students on to tackle each activity. She took three students to the Gulf of Alaska four times to acquire all the footage needed for the video. Another student back in Chicago tackled the animation. A fifth student illustrated the cards, and a final small student team coded the video game.

The advantage with students, who Hoffman-Trotter stresses did get paid to do the work, is that they’re eager for opportunities to get on a boat and film in the Gulf of Alaska for long stints of time. Hoffman-Trotter mentors them in whatever media they’re working in, and in addition to compensation, they can often leverage the work for additional class credit.

Media is a permanent resource

While the benefits of a successful LTER education project are clear—students are taught how to think like an ecologist, crucial training for the next generation of scientists—the media developed for the project remains useful in unexpected ways.

For example, the video footage Michele’s team collected was incredibly valuable for the Northern Gulf of Alaska’s site renewal process in 2022. Pushed online by the pandemic, site leadership needed a way to show NSF program officers what was going on at their site from behind a computer. The virtual field trip’s treasure trove of high quality footage gave the NGA a great starting point to develop their virtual site visit.

And even though the field trip is targeted towards middle school students, the process of translating complex primary science into straightforward concepts and plain language has reaped rewards. “I’ve used some of some of the language that we developed for the virtual field trip when asking for funding,” Katie says. “We also used a lot of the language and materials from a virtual field trip in a project with other Alaskan university professors looking at creating modules for undergrad students with Alaskan data. I’ve sent it to incoming graduate students,” she adds, noting that even higher-ed students benefit from the straightforward, simplified concepts.

It’s rare that scientists, students, educators, and media specialists all get together to work on a project. Translating science across disciplines and media types comes with huge inherent challenges. But there are huge benefits as well. Out in the world, free for anyone to use, the NGA’s virtual field trip can help students far and wide learn about a remote part of our world. It can connect local communities near the Gulf of Alaska that would never have the opportunity to visit the site. And it can teach others far and wide about food webs and marine ecology. Take a visit to the NGA—it’s just a click away, after all.

by Gabriel De La Rosa