A new analysis of Moorea Coral Reef LTER data shows that grazing has an insignificant effect on coral reef recovery after disturbance. The results, published in Nature Ecology and Evolution, suggest that other factors—nutrient pollution, climate change—vastly outweigh any positive effects of grazing on coral reef recovery. The paper is the first to explore how fish herbivory affects coral recovery at the ecosystem, rather than experimental, scale and is the result of years of high quality data collection in Moorea.

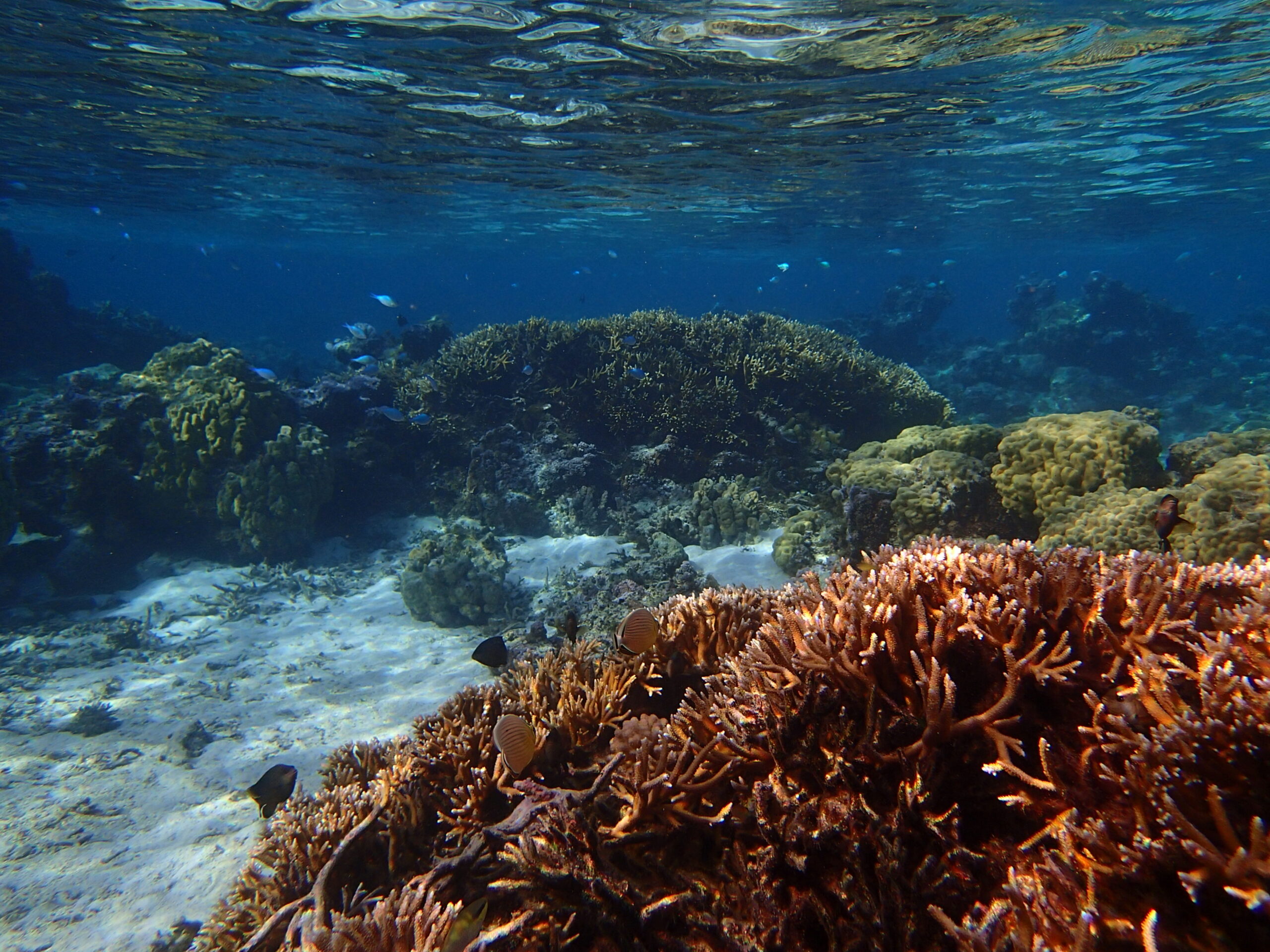

Moorea’s vibrant coral reefs are found in shallow water, which spurs competition between corals and fast growing photosynthetic algae.

Credit: Kelly Speare, CC BY-SA 4.0

Grazing is one of many drivers of reef recovery

Fish exert strong influence over coral growth. Reefs are inherently space limited—tropical corals can only grow in relatively shallow depths—and fast growing algae competes for that limited space. Grazing fish can keep algae at bay, giving corals the chance to find space to grow. Experiments in reefs all over the world show that fish grazing clears space and allows young corals to establish, leading many to predict grazing may spur reef recovery after disturbances such as bleaching or hurricanes. Plus, a handful of studies show that fish excretion boosts coral growth as well, adding another positive mechanism towards coral recovery.

But a new study by Drs. Timothy Cline and Jacob Allgeier, published in Nature, shows that grazing may play less of a role in coral recovery than some have predicted.

Moorea harbors a wide diversity of both corals and fish, with intricate relationships between the two.

Credit: Kelly Speare, CC zby-SA 4.0

Using time series data from the Moorea Coral Reef LTER, Drs. Cline and Allgeier tested the influence of grazing on coral recovery in fifty-eight different sites across the LTER. The dataset, spanning 14 years, surrounded two significant disturbances: a coral-eating crown of thorns starfish outbreak and Cyclone Oli.

Notably, while Dr. Allgeier has conducted his own research at the Moorea LTER, this rich dataset was already complete and waiting to be analyzed.

The sites showed a range of coral recovery after each disturbance: some reefs regained their lost expanse of coral, while others never recovered. The data also included fish community attributes—richness, biomass, and diversity, for example—broken down by fish functional groups, such as grazers, scrapers, and herbivores.

If fish really do influence coral recovery, Drs. Cline and Allgeier hypothesized, one or some of these fish community attributes should correlate with the level of recovery found on reefs. “There’s no argument that on small scales, fishes have this tremendous impact on these systems,” says Dr. Allgeier. “But is there an emergent effect at the ecosystem scale?”

When they scoured the data, nothing stood out.

A thousand models, no results

To test their hypothesis, Drs. Cline and Allgeier compared mixed effects models that predicted coral recovery based on fish community attributes, the type of reef habitat, and the location of each site. They compared models that included fish community attributes to a control that did not. And no matter how they structured their model—there are twenty-seven pages of tables outlining each combination of community attributes they tested in the paper’s supplementary materials—including fish never improved the predictive power of their models on reef recovery.

Yet another reef topolography in Moorea. This study sampled many different reefs and locations on each reef across the LTER.

Credit: Kelly Speare, CC BY-SA 4.0

Scaling up

The evidence for the influence of grazing at small scales is so strong that Drs. Cline and Allgeier wanted convincing evidence that they hadn’t somehow missed an effect in their data.

So they decided to challenge their models with the specific cases where fish were the most likely to influence coral recovery. The authors parsed their dataset down to a few reefs that showed dramatic recovery after disturbance. “We cherry picked sites that have strong variation where you would be able to pick out a good statistical signal,” says Dr. Allgeier. But even in these best-case scenarios, other factors swamped any influence of fish grazing.

Human influence outshines grazing in Moorea

Dr. Allgeier is quick to point out that these results don’t necessarily contradict the many experiments that show grazers mediate coral recovery at small scales. Instead, he continues, other processes probably dramatically outweigh any influence fish have on coral recovery at the ecosystem scale in Moorea.

Complementary research at the Moorea LTER does show that other factors, such as climate change or nutrient pollution, significantly influence coral mortality and recovery. Dr. Allgeier says that this study lends more evidence that these human impacts drive recovery, or lack thereof, in these reefs.

And yet, coral reefs are not homogenous across the globe. Moorea reefs have relatively low fish biomass in general, and the human communities that live nearby dramatically alter the reefs through fishing or pollution. In another system, with higher fish biomass and fewer human impacts, grazing may play a more critical role in coral recovery. “To be clear, I think in a vacuum that we likely would have found an effect of fish,” says Dr. Allgeier. But in Moorea, “we don’t live in a vacuum,” he adds.

The experiment highlights the need to contextualize small scale experiments in a whole ecosystem. Yet only the reefs at the Moorea LTER had enough data to search for fishes’ influence on coral recovery. The long term research program was already in place when two major disturbances struck the reefs, then continued to collect data as some reefs recovered but others did not. Without similar high quality data, it would be impossible to apply a similar approach to identifying influences on coral recovery in other reefs.

Induced recovery

The paper also highlights the importance of long term, ecosystem wide data for conservation and restoration. “There aren’t that many studies that have looked at these processes at scale”, says Allgeier. “And it’s hard to do because you really need time.” It’s easy to assume that the processes discovered via small-scale experiments scale up to the entire ecosystem. But had Moorea protected grazers without looking to see if the grazing benefits still emerged at the ecosystem scale, their conservation and recovery efforts would have been misguided.

That’s why long term projects like the Moorea Coral Reef LTER are so important: high quality, long term data, coupled with a deep knowledge of place and process, plus enough time to capture significant variation and occasional disturbance, are truly necessary to understand how ecosystems function. And in a world of rapid change, that holistic view is critical to protecting fragile ecosystems like coral reefs.

By Gabriel De La Rosa