Credit: Moorea LTER

This post is part of the LTER’s Short Stories About Long-Term Research (SSALTER) Blog, a graduate student driven blog about research, life in the field, and more. For more information, including submission guidelines, see lternet.edu/SSALTER

by Adelaide Dahl

There was a trail I would frequent when I was younger, wrapped around a pond in the pines of New Hampshire. Each day, I would tread the soft bed of fallen pine needles, navigating disguised roots and rocks to reach my destination: a small dock along the edge of a pond. This route became a daily ritual, and soon, a game, as my childhood friend memorized every curve and wind of the trail. We became familiar with each root and stump, deftly avoiding hidden hazards. Running along the trail, eyes closed, we challenged each other to navigate without stumbling. Each rock threatened to grab our feet and disrupt the steady pad of our footfalls, but we knew the path well. Each pass we made without stumbling solidified our confidence and familiarity and heightened our awareness to changes in the surrounding forest. Repetition led to reinforced understanding and allowed us to perceive more deeply – each day on the path brought new discoveries and observations, enriching our experience.

Credit: Adelaide Dahl, CC BY-SA 4.0.

In Moorea, the MCR LTER has formed a path for many researchers. As a wide eyed REU student in 2022, I arrived at the Gump station with extensive theoretical knowledge but lacking firsthand experience of Moorea’s reefs. Challenged to apply my absorbed understanding practically, I embarked on surveys of the reef, developing my project and curiosity to the new environment. Interested in the invertebrates hiding among the corals, I began to stick my head into nooks and crannies, investigating which creatures tended to reside in the reef habitat.

Credit: Adelaide Dahl, CC BY-SA 4.0.

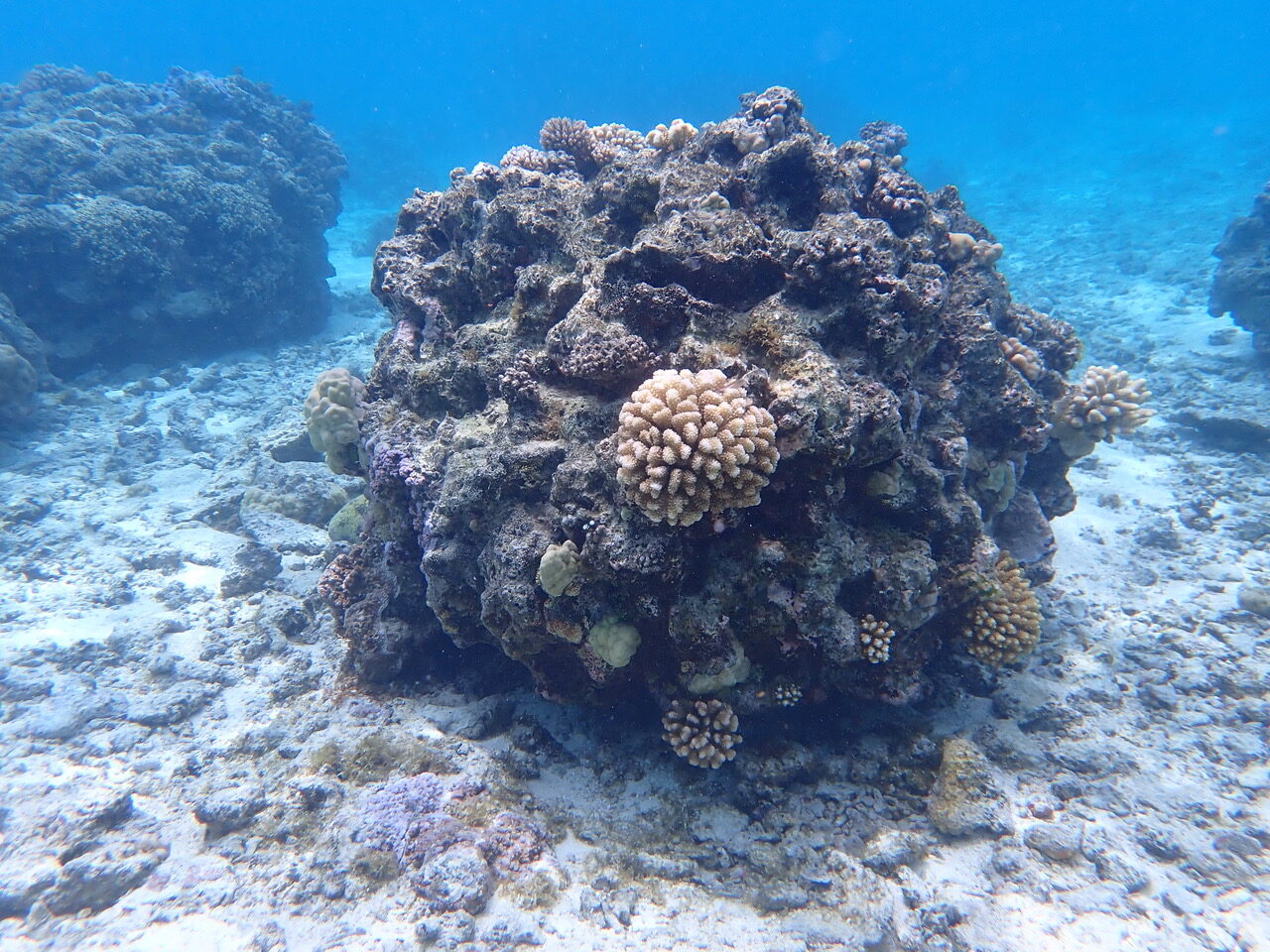

The shallow reef in Moorea is primarily shaped by coral “bommies”, three-dimensional structures formed by the skeletons of dead corals and other calcifying organisms. These bommies provide habitat for various organisms, some conspicuous, like the large branching Acroporid corals, which add structure to the bommies and provide refuge for smaller fishes. Others are subtle, camouflaged within the bommie or burrowed below the exterior. My specific question addressed the nature of asymmetry on the bommies, how corals might exhibit asymmetrical growth that would impact the structure of the habitat itself.

I would return to the same bommies each day and, as I did on the well-worn trails of New Hampshire, noticed something new with each dive. Initially, the corals dominated my attention, jutting off the main body of the bommie to declare their presence against the watery backdrop of reef. The branching and plating corals were the most conspicuous, stretching up and out and contorting as they competed for space or light with the corals growing nearby.

Credit: Adelaide Dahl, CC BY-SA 4.0.

Gradually, I noted other creatures that were mainstays of the same bommies; an urchin I assumed to be returning to the same alcove after venturing out to feed each night, cryptic coral species which occupied darker niches of the structure, and even a tiny mantis shrimp which shuffled out of a crack to investigate the source of the noise as my SCUBA bubbles gurgled past.

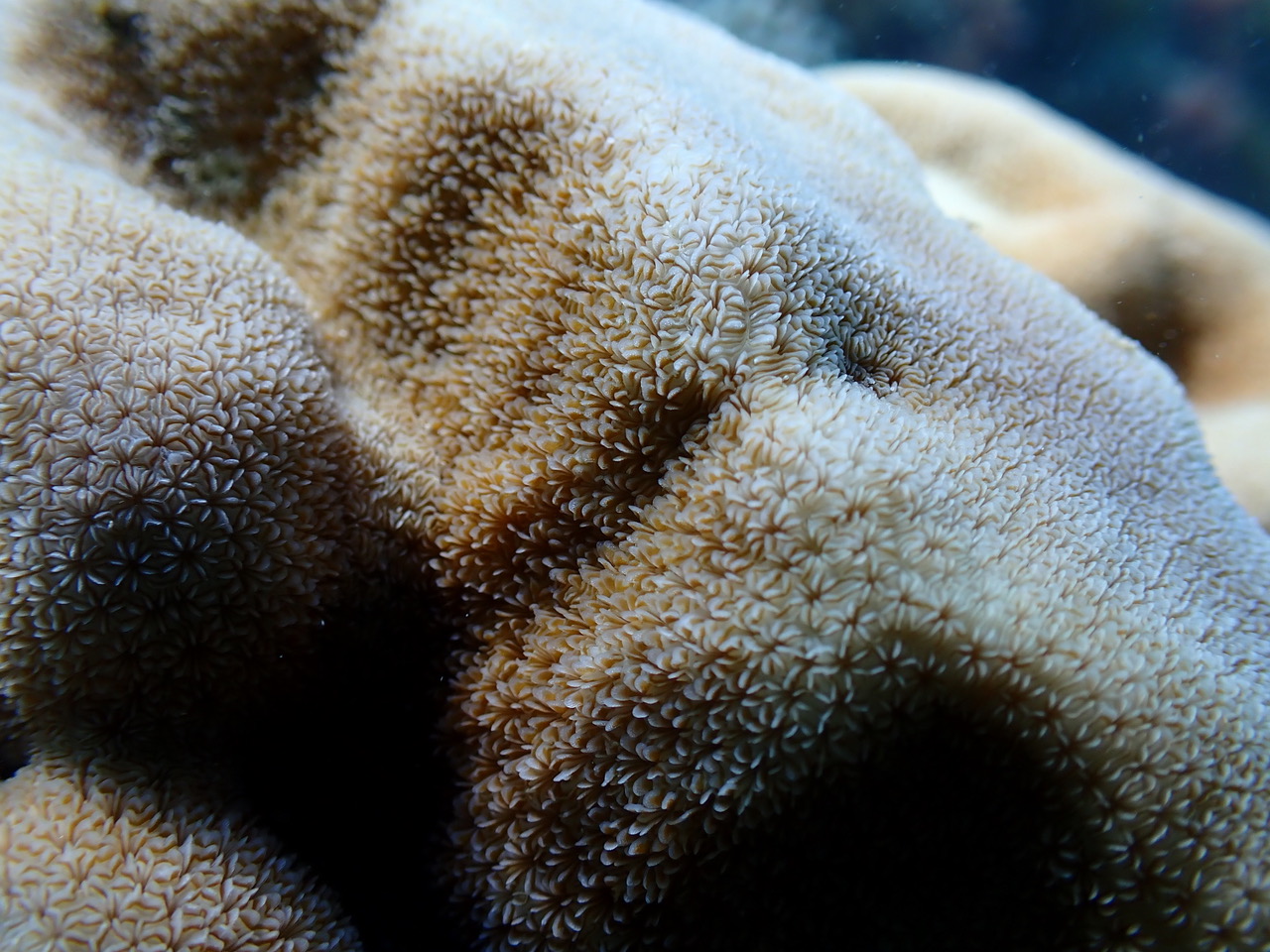

Contorted upside down and backwards, my face pressed into the smallest openings, I marveled at the mesmerizing whorls of the corals’ skeleton. Occasionally, a face looked back at me – the eels in Moorea can frequently be seen in the cool interior of the bommies, sometimes emerging to leer at me. I would quickly withdraw a hand at the hint of a lurking eel under the canopy of algae. As time went on, I learned the bommies to avoid, and on a couple of occasions got lucky to spot a sleepy octopus or a shark nestled under the protective canopy.

Credit: Adelaide Dahl, CC BY-SA 4.0.

Returning to the same structures not only deepened my understanding of the reef’s intricate ecosystem but enabled me to notice more subtle creatures residing within the bommies. As my journey as an REU student transitioned into the pursuit of a master’s degree at California State University, Northridge, the observations from the reef have become the foundation of my thesis project. For my master’s thesis, I have turned my attention to the intersection of structure and diversity once again, seeking to apply foundational ecological theory to a modern reef. Focusing on the biological diversity of invertebrates living on and within the ever-changing bommie structures, I am investigating the implications of fragmentation in Moorea’s shallow reef. Staying on alert for eels and taking time to appreciate the elusive creatures, I find myself continually drawn back to the importance of spending repeated time in the same place, a practice that has not only shaped my scientific approach but also heighted my appreciation for the incredible ecosystem in Moorea.

Adelaide Dahl is in her second year of a master’s program in Dr. Peter Edmunds’ lab at California State University, Northridge. Her research focuses on the impact of habitat fragmentation on biological diversity of invertebrates in shallow reefs systems. See https://www.linkedin.com/in/adelaide-dahl/ for general updates on her work and to stay connected!