Styrofoam heads and odd scientists, before shrinking.

Credit: Jennifer Brandon

For our research in biological oceanography, we often have to go to sea to collect our biological samples or to measure the temperature, salinity, and chemical components of the water at different depths. We often have to go to sea for days, even weeks at a time without coming into port. Going to sea is a very fun and unique part of our jobs, and allows us to answer really unique questions, like “What are the ecological effects on plankton and fish communities when a large El Niño is occurring?” or “How much plastic debris is in the water in the middle of the North Pacific Gyre?” These are questions we can’t answer from land, or from satellite images. But it does lead to one unique problem that we get asked quite often: What do you do to entertain yourself for a MONTH at sea without good INTERNET??

1. Watch a lot of movies.

a. You can’t rely on Netflix or hulu out there at sea, so you better have that series you’re ready to binge-watch stored on your computer or on DVD. I foolishly brought my own DVDs on the R/V Melville the first time, only to walk into the movie room and discover hundreds upon hundreds of DVDs. On shelves in rows three DVDs thick, in binders that were once organized, in binders where there were unlabeled DVDs, in binders where you find the occasional mix CD from a decade past. So needless to say, there are hundreds of DVDs to watch, if you have the patience to find what you’re looking for.

There are no pictures of us watching movies, so here’s a lovely sunset view from the ship instead.

Credit: Jennifer Brandon

2. Read books. That’s right, books.

a. This one fully depends on your ability to read without getting seasick, and thus also on the calmness of the sea. But it is actually really nice to disconnect, unplug, and read those books gathering dust on your shelves rather than yet another buzzfeed article. Because buzzfeed is not loading at sea, friend. So stop trying. The R/V Melville and some other vessels even have libraries where you can read the books left behind by past sailors and scientists. Both the library and movie room shelves have brass bars across them to keep the books and DVDs in place on rough seas.

Library on the R/V Melville.

Credit: Jennifer Brandon

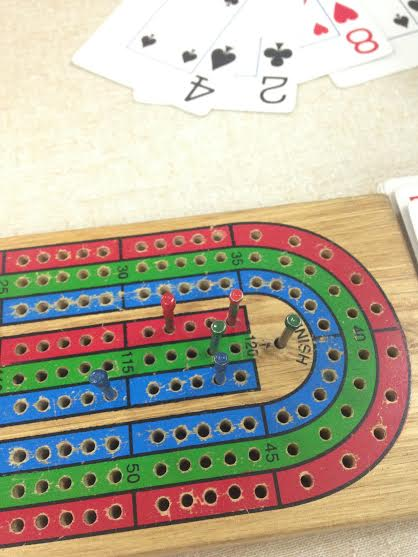

3. Play cribbage.

a. I had never played cribbage, and had really barely heard of it, before my first cruise. This is an old sailor favorite, and the crew of almost any ship will be playing it after dinner. If you’re nice, they’ll teach you how to play. One of the benefits of playing at sea is that the pegs won’t move in rough weather. Not so with Mah Jong tiles, which was a sailor favorite on one of our cruises due to the ship having just been dry-docked (laid up for service) in Asia. Those tiles are slippery, and moved all over with the roll of the ship. It was quickly abandoned for cribbage.

Cribbage time!

Credit: Jennifer Brandon

4. Draw on cups. And foam heads.

a. What? You’ve never done this? This age-old seafaring tradition actually can’t be any older than 1954, when Styrofoam was invented. What we do is draw on Styrofoam cups and heads with sharpies at the sea surface. Then we attach the cups to a CTD rosette, a water sampler, as it goes down on a deep dive. The air in the Styrofoam escapes under the increased pressure at depth, and the now air-free cups shrink. This shrinking is a one-way process, and the cups come back to the surface much much smaller! The deeper the dive, the smaller the cups. These shrunken cups and heads are a triple-threat as a favorite cruise pastime, our favorite cruise souvenir, and the cheapest gift to make for friends and family.

More shrunken sytrofoam heads and cups.

Credit: Jennifer Brandon

Shrunken styrofoam cups that went 3500 meters under the sea!

Credit: Jennifer Brandon

5. Do science.

a. What we actually spend almost all our time doing is of course not watching movies or playing cribbage, but collecting samples and deploying equipment. Going to sea is amazing because we get to interact with all those preserved animals we have seen back in the lab freezers and in jars of formaldehyde, but we see them in vibrant color, alive and moving. I get to see how that salinity and temperature data is collected, and what all those labs on my hall actually do to get their samples. The best thing to do when your shift ends on a cruise is to volunteer at least once a cruise to help with every other shift to really see what each group does and how they collect their samples. Then when you need that data back in lab, you have a holistic understanding of where it came from, and how the CCE functions together.

Scientists enjoying the sun on deck during a break.

Credit: Jennifer Brandon

Setting up scientific equipment in the ship’s lab.

Credit: Jennifer Brandon

Deploying an enormous net, called an Oozeki net, that will be dragged behind the boat to catch fish and other exciting creatures from deep in the water.

Credit: Jennifer Brandon

Sifting through what was caught in a trawl net, including an absurd amount of urchins.

Credit: Jennifer Brandon

(Top) Scientists enjoying the sun on deck during a break. (Bottom left) Setting up scientific equipment in the ship’s lab. (Bottom middle) Deploying an enormous net, called an Oozeki net, that will be dragged behind the boat to catch fish and other exciting creatures from deep in the water. (Bottom right) Sifting through what was caught in a trawl net, including an absurd amount of urchins.

Jenni is a fourth year PhD candidate at Scripps Institution of

Oceanography in San Diego, CA. She quantifies the spatial and temporal distribution of marine microdebris and studies the ecological effects of marine debris. She loves Duke basketball, Giants baseball, and traveling as much as possible.