Left: Suzanne Strom is a leading expert in labeling tiny sample vials on a moving boat, like this particulate organic matter sample. Center: Dr. Ana Aguilar-Islas exudes genuine positivity at all times, but especially when we explore glacial fjords. Right: Kelley Bright measures the chlorophyll fluorescence of water samples collected in the Northern Gulf of Alaska.

Credit: Megan O`Hara, CC BY-SA 4.0

by Megan O`Hara, PhD student at Western Washington University

In the past century there has been a dramatic shift toward empowering women in the workforce. However, males remain dominant in many realms of marine science. Despite females earning a greater proportion of advanced degrees in oceanography in 2020, males held more senior faculty positions and published more first-author peer-review papers. Many of the documentaries, presentations, and much of the literature that inspired me to pursue oceanography was created by men.

I worked in a male-dominated industry as a marine naturalist on ecotourism boats in Alaska and Hawaii. During my years working on the water I was consistently captivated by the oceanographic laboratories floating on the horizon. Rather than tending to my responsibilities as a whale watching marine naturalist, I found myself consumed by unrestrained curiosity every time I spotted a research vessel. Each distant encounter left me with the desire to be a stowaway on a research cruise so I could witness oceanographic science in action.

I am proud to say that I am becoming acquainted with my wildest dreams. Today I study plankton ecology at the Northern Gulf of Alaska LTER (NGA-LTER). The Gulf of Alaska offers profound economic, ecological, and spiritual importance to both surrounding communities and to the entire Pacific Ocean. When I stepped aboard the R/V Sikuliaq research vessel for the first time, to my surprise, I found myself surrounded by remarkable women. I spent several weeks at sea learning to sample, study, and analyze the ocean from accomplished female oceanographers. Below I highlight three women aboard the R/V Sikuliaq who were particularly meaningful to my first oceanic voyage, and who continue to be pillars of the oceanography field.

A Fearless Leader: Dr. Suzanne Strom

Suzanne showcases how to best don a “one size fits all” survival suit.

Credit: Megan O`Hara, CC BY-SA 4.0

Dr. Suzanne Strom, my graduate advisor and a principal investigator for the NGA-LTER, has studied the Gulf of Alaska since 1987. Suzanne has advised over twenty graduate students, published more than 70 peer-reviewed scientific articles, presented over 40 papers at national and international scientific society meetings, and helped establish a collaborative long-term research program in the Gulf of Alaska. Her research focuses on planktonic food web interactions and how climatological patterns influence the resiliency of the NGA-LTER food web. Suzanne balances her long-term career in academia with raising a family, volunteering, and staying practiced in music and dance.

During her career as an oceanographer, Suzanne faced harrowing storms at Ocean Station Papa in the North Pacific Ocean and thirty-foot seas while crossing the Drake passage to the Southern Ocean. Despite innumerable experiences in rough seas, Suzanne asserts that many of her greatest challenges came as a graduate student in the 1980’s. She was fortunate to have mentors that supported her as a first-time mother and treated her as an equal to her counterparts. Nonetheless, she encountered systematic bias as the only female researcher in the lab, including the denial of health insurance upon the birth of her second child and unequal consideration of her ideas and opinions. The unique combination of female scientist and mother left Suzanne feeling unsupported at that point in her career.

Despite overcoming these hurdles, Suzanne still asserts that the field of oceanography is a work in progress. “It was not that long ago that it was considered extremely unlucky to have any woman on a ship”, she jokes. An ancient sea-faring superstition claims that women anger the sea gods, causing violent weather to take revenge on vessels bearing women. Because of this archaic myth and entrenched attitudes about the feebleness of women, the first female oceanographers were not allowed to study aboard research vessels until 1959.

Today, Suzanne notices that women are becoming increasingly empowered to advocate for themselves and stand up to discrimination. “Progress is happening,” she says, “but not fast enough.” Suzanne hopes to see more women excel to the highest levels of science decision-making as members of advisory committees and funding agencies. Likewise, Suzanne is confident that greater institutional support for women with families, a revised funding review process, and more effort from the entire research community to generate an equitable field will incentivize women to pursue careers in research.

In addition to her role as an advocate for women in oceanography, Suzanne has personal goals still to accomplish. She plans to publish conceptual papers surrounding long-term data on the spring plankton bloom in the NGA and is committed to bonding the science team through a choreographed hip-hop dance aboard the R/V Sikuliaq.

The Microzooplankton Master: Kelley Bright

Kelley, the award-winning “best pourer” of the NGA-LTER, filters a deck-board incubation experiment.

Credit: Megan O`Hara, CC BY-SA 4.0

Dr. Suzanne Strom is the first person to admit that her success necessitates endless behind-the-scenes work by her super-skilled laboratory technicians. Kelley Bright, a laboratory technician in the Strom lab, has worked at Western Washington University’s Shannon Point marine lab for 27 years and is essential to Dr. Strom’s success.

As an invaluable member of the Strom lab, Kelley is valued for her expertise. She holds the honor of being one of the longest running employees at the marine lab. One of Kelley’s most impressive career accomplishments is isolating and culturing sensitive microzooplankton species to support laboratory research around the world. Yet, as an early-career scientist, she did not feel like her voice was heard. After receiving her bachelor’s degree in biology and chemistry, Kelley washed dishes in a microbiology laboratory to gain experience in the field. She recalls this as a time when people were not held accountable for how they spoke to each other, particularly to women.

Plankton culture isolation is difficult and keeping these cultures alive is even more challenging. Microzooplankton have a habit of exploding when exposed to tiny bubbles, so maintaining these cultures requires surgeon-like skills. Regarding her remarkable talent for keeping plankton alive, Kelley humbly remarks, “As a research assistant I’m supporting other scientists. It’s not a glorious job, but it is something that I care about.” Thanks to her meticulous caretaking, countless laboratory studies have yielded novel information on microplankton ecology. In the coming years Kelley hopes to help uncover the mysteries of understudied protists in the NGA, specifically cells that can both feed and photosynthesize.

When I asked Kelley about progress for women in marine science, she notes that there are now more women in leadership positions than when she started her career in 1988. Kelley hopes for a future of oceanography when race and gender do not diminish a person’s freedom to share their opinion. She says, “When you value someone’s opinion you realize that you can gain something from their knowledge.” She looks forward to a time when young girls can pursue their oceanographic dreams without limit.

The Iron Maiden: Dr. Ana Aguilar-Islas

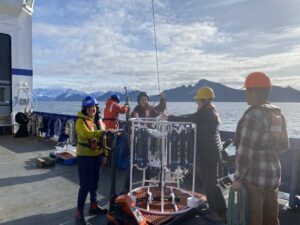

Ana and her lab team prepare to deploy a trace metal CTD on an unusually sunny day in the Northern Gulf of Alaska.

Credit: Megan O`Hara, CC BY-SA 4.0

As a forty-four year old oceanography graduate student, Dr. Ana Aguilar-Islas frolicked on Southern Ocean sea-ice while Adélie penguins waddled by, a Minke whale floated in the hole created by an icebreaker, and scientists danced and played frisbee under the midnight sun. Ana received a PhD at forty-four years old after shifting career focus from graphic design. On being told that a career in academia was out of the question due to her age, Ana remarks “I did not listen very well to that advice.” She became an associate professor at the University of Alaska Fairbanks in just a few short years.

Ana is a leading expert in Arctic marine biogeochemistry and a principal investigator for the NGA-LTER. Her research focuses on trace metal speciation and distribution in the NGA and how essential trace metals, such as iron, impact the ecosystem. Anyone that spends time at sea with Ana will remark that she exudes positivity and works tirelessly, yet somehow always offers to lend a helping hand to fellow scientists.

When asked about her future career goals Ana said, “In terms of science, one of my goals is to better understand the cycling of nutrients in sea ice, and its role in the primary production of sea ice-covered regions.” In addition to her research goals, Ana hopes to enhance diversity in oceanography and make careers in research more appealing to women and girls.

Statistics don’t tell the whole story

The Strom Lab taking over the wheelhouse on the R/V Sikuliaq.

Credit: Megan O`Hara, CC BY-SA 4.0

These women shattered my expectations of a male-dominated research cruise. Women spearhead oceanographic research in the NGA-LTER. However, even these accomplished scientists note that both subtle and obvious discrimination continue to prevent female scientists from achieving equal success to their male counterparts. With increased societal awareness and institutional support for women in science we can close this gender gap and open access to oceanography for women of all races and backgrounds.

Collectively Suzanne, Kelley, and Ana have spent nearly five years at sea, processed millions of samples, mentored countless undergraduate and graduate students, published hundreds of scientific papers, and improved our understanding of the Northern Gulf of Alaska. They hurdled obstacles and fought to deconstruct biases against women in oceanography. I am privileged to work alongside each of these brilliant role models! Although women in oceanography are underrepresented, the women of the NGA LTER are accomplished scientists who continue to pave the way for and inspire future generations of female oceanographers.