A new paper from the Minneapolis-St. Paul LTER shows that properties that had a racial covenant have better access to environmental benefits than those without.

Look at a forest from above, and you’ll find a patchwork of vegetation: water loving plants follow the streams, trees with deep roots tap into groundwater far from those rivers, shade tolerant plants thrive in their shadow. In every ecosystem, patterns emerge from the interplay between physical forces that shape the environment—water availability, erosion, sunlight—and the dynamics—competition, mutualism—between the living things that call that environment home.

In an urban ecosystem, those underlying forces include the patchwork of concrete and green spaces, water availability dictated by sprinklers and runoff, and, perhaps more tangibly than any other ecosystem type, the decisions and actions of human beings.

Credit: jpellgen, via Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

A new paper from the Minneapolis-St. Paul LTER site connects the present-day structure and function of the urban ecosystem to racially discriminatory housing policies implemented in the city’s past. Heat exposure and forest cover were both tightly correlated to the presence of racial covenants, or contractual agreements that explicitly prohibited the sale of property to certain groups of people (covenants almost universally restrict property sales to white people). In other words, a property which once had a covenant was more likely to receive environmental benefits and avoid environmental harm today.

The implications of these covenants manifest today in two distinct ways: first, the underlying pattern of the urban ecosystem reflects the spatial distribution of covenants, but covenants similarly pattern the current distribution of people around the city. As a result, covenants structure different groups’ access to environmental benefits and exposure to environmental harms, with the result being that marginalized groups often suffer more harms and receive fewer benefits today, as well as in the past.

Had a covenant? Get some benefits.

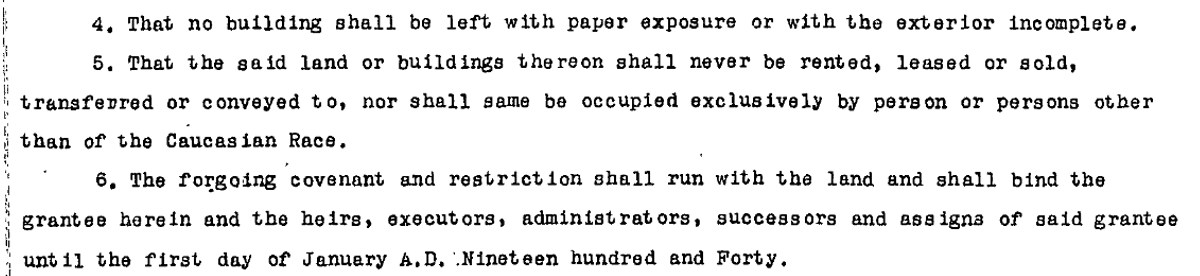

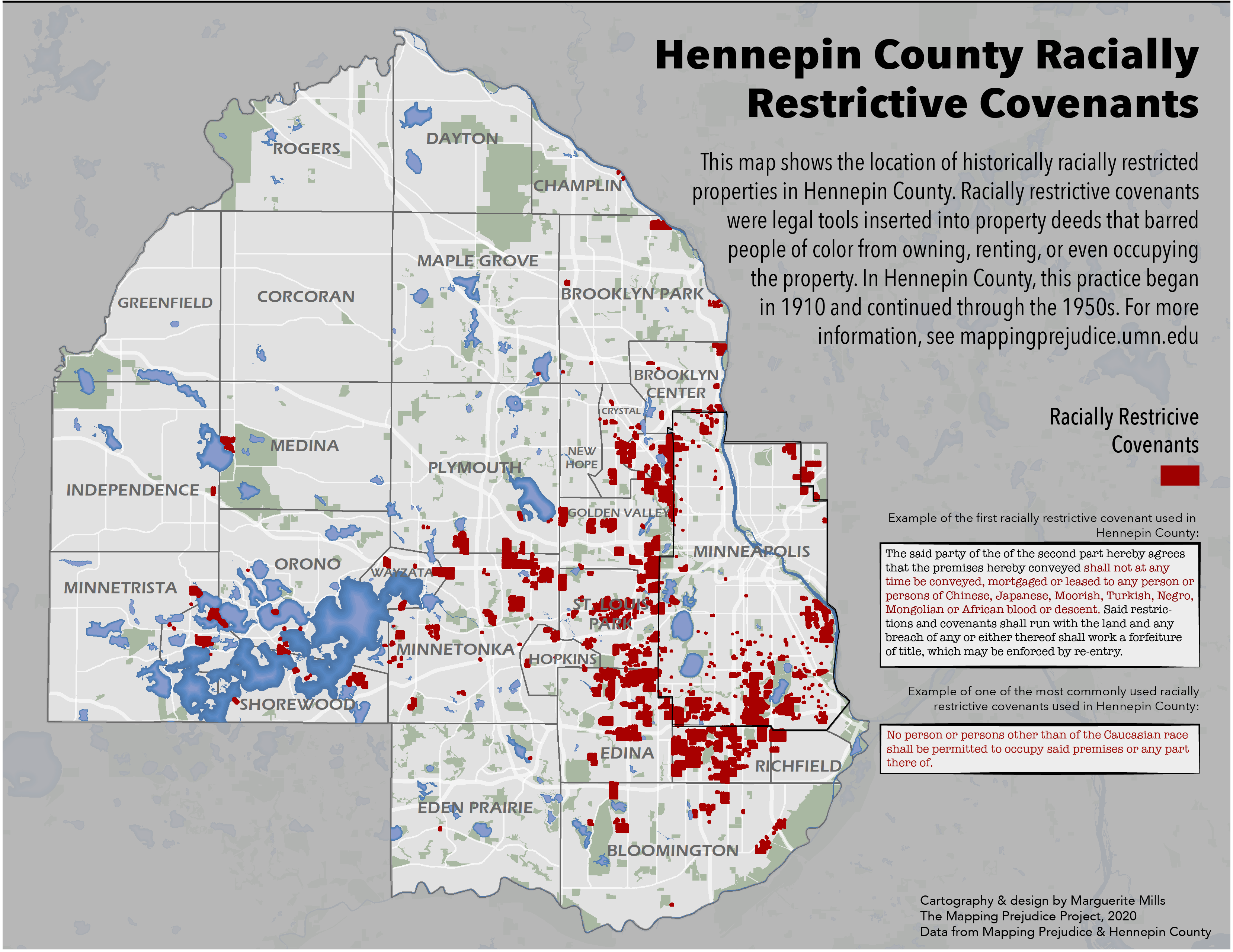

Racial covenants are one of several discriminatory policies that have shaped the structure of American cities. Covenants refer to explicit statements in property leases or deeds that dictate who can buy property. For example, in one lease from Hennepin County, Minnesota, a clause reads that “the said premises shall not at any time be sold, conveyed, leased, or sublet, or occupied by any person or persons who are not full bloods of the so-called Caucasian or White race.”

Credit: Courtesy of the Mapping Prejudice project, CC BY-NC 4.0.

Armed with a new dataset describing the spatial distribution of covenants around the city, Dr. Rebecca Walker, lead author of the paper and professor at the University of Illinois-Urbana Champaign, and her team looked to see if covenants correlated with three environmental variables: temperature, tree canopy cover, and impervious surfaces. The three metrics were specifically chosen because of the impacts they have on people and the environment nearby: Minneapolis has seen a recent increase in extreme heat, with detrimental effects to local residents; tree canopy cover can temper that heat but also provides many additional environmental benefits; and impervious surfaces are tightly linked to water quality and flood risk.

The presence of a racial covenant, the team found, was associated with higher tree canopy cover, lower impervious surface cover, and reduced exposure to extreme heat across the city. In other words, a property which once had a covenant was more likely to receive environmental benefits and avoid environmental harm today.

The team also overlaid the present day racial demographics of the city with historical covenants. Today, historically covenanted properties are nearly eighty-five percent white, though the entire city is only 60 percent white as a whole. The environmental benefits incurred by the historical presence of a covenant are disproportionately received by white residents.

“Even as the city has become more and more diverse, these covenants and the historic legacies of discrimination have continued to shape where people live and where people feel welcome,” says Dr. Walker. “Those legal guarantees of whiteness continue to afford environmental privilege even today, 50 years after they were ruled illegal by the Fair Housing Act. That to me is pretty crazy.”

Redlining impacts environmental benefits, too

Covenants are distinct from other discriminatory housing policies precisely because they are attached to an individual property. That’s different from redlining, which refers to discriminatory lending practices designed to prevent certain groups of people, mainly people of color, from receiving home loans. Whereas redlining practices are instigated by banks and the federal government and were implemented across whole neighborhoods, covenants are the actions of individual homeowners or developers.

Minneapolis also had redlining policies, however, and the team wanted to parse the effects of covenants from those of redlining. This analysis relied on mortgage security maps—aka redlining maps—developed by the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation, a mortgage lending entity established by the U.S. Government and instrumental in redlining cities. These mortgage security maps ranked individual neighborhoods’ mortgage lending risk, based, in part, on their racial demographics.

Walker and her colleagues first showed that highly ranked neighborhoods (low lending risk, and redlined to be predominantly white) have greater environmental benefits than those with lower rankings in Minneapolis. This was no surprise—a growing body of literature, including work from the Baltimore Ecosystem Study (LTER site from 1997-2021), shows that redlining in cities across the country dictates access to environmental benefits.

Credit: Warren LeMay, via Flickr, CC BY-SA 2.0.

Covenants have more impact than redlining across the city

But how do covenants compare to redlining, in a city with both policies? Do covenants confer additional environmental benefits beyond those patterned by redlining? To answer this question, the authors looked at whether the presence of a covenant changed tree canopy cover, heat exposure, or impervious surface cover within neighborhoods that received the same mortgage security grade.

In the most “undesirable” neighborhoods, in terms of their mortgage security grade, the presence of a covenant correlated with a significant reduction in heat exposure, a reduction in impervious surface area, and an increase in canopy cover compared to property without a covenant. In fact, covenanted properties in poorly ranked areas showed similar environmental benefits to properties in neighborhoods in the highest ranked areas. Their neighbors without covenants, however, did not share those benefits. “[Those benefits are] specifically tied to the covenant,” says Dr. Walker.

New data leads to new insight

This work relied heavily on a covenant dataset generated by the Mapping Prejudice Project, a nonprofit group that uncovers historical patterns of racial discrimination. Founded in Minneapolis, the nonprofit began sorting through records in their local area, generating a rich dataset detailing the history of covenants in the city, property deed by deed. “We’re lucky to be partners with Mapping Prejudice,” says Dr. Walker. She notes that Minneapolis was the first location for which a comprehensive covenant dataset was available, and as a result, this work is the first to link covenants to the spatial distribution of environmental benefits.

Credit: Mapping Prejudice Project.

Redlining data, by contrast, is more readily available. Because redlining policies apply across neighborhoods, sourcing data is relatively simple—one policy covers a fairly large area. Covenants, however, are specific to individual leases, and generating a dataset of covenants across an entire city requires sifting through individual deeds.

While this work shows that redlining has a significant impact on access to environmental benefits across Minneapolis, it also highlights the importance of other policies—and underscores the need for additional hard needed to compile datasets that allow researchers to study their impacts. Fortunately, Mapping Prejudice plans to expand this covenant work to other cities.

All about structure

To Dr. Walker, covenants show that structural racism reaches beyond bureaucratic institutions. “I think it’s important that we look at the history of racial covenants in particular, because covenants implicate all of us,” she says. “All of us in some way benefited from or are part of the system that enabled racial covenants to exist. Individual developers added covenants to their development. Local governments allowed those developers to do so, and then individual homebuyers bought those homes, especially white homebuyers. And so all of those different entities have some responsibility for addressing those past harms, and need to be part of the solution of advancing environmental justice today.”

With redlining, it’s easy to blame the federal government (the Home Owners Loan Corporation was a federal government sponsored institution created in the 1930s) for the patterns in cities today. With covenants, the blame extends much farther. Understanding how covenants, redlining, and other discriminatory policies shape the urban ecosystem and affect the people who live there lays the groundwork for remediation.

That extends to ecological remediation, too. “Work that I’m really excited about is taking this understanding of social processes and integrating it back into ecological theory,” says Dr. Walker. This covenant work is just a small piece of that puzzle. “These decisions shape the urban ecosystem in these real, tangible biophysical ways.” Covenants are one way, as are redlining initiatives. So are freeways, the placement of public parks, and front lawns, among many other things. To understand Minneapolis-St. Paul as an ecosystem, researchers at the MSP LTER must uncover how humans have shaped its patterns and processes. This work begins that effort.

by Gabriel De La Rosa