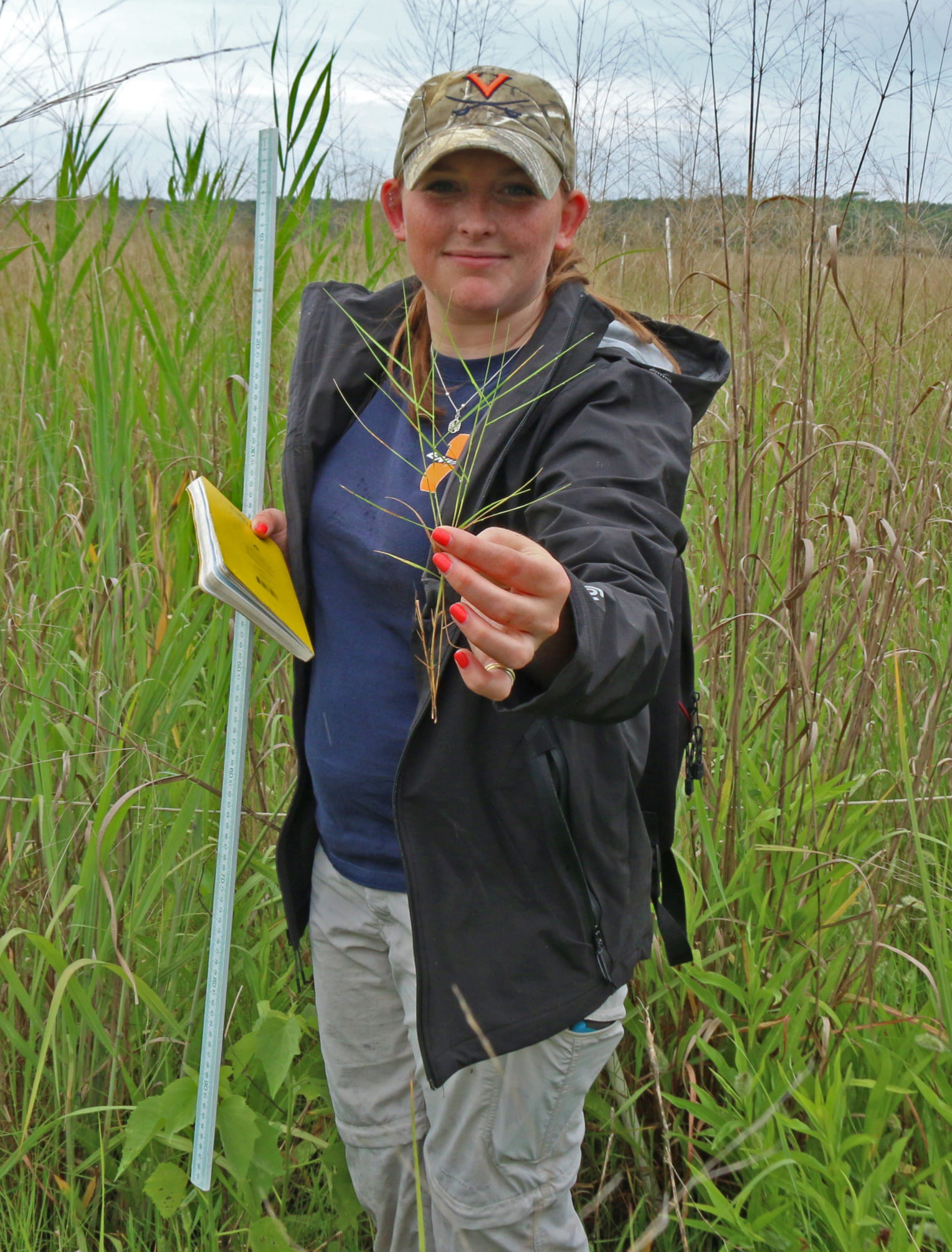

PhD student Victoria Long displaying one of the plant species at her study site along Virginia’s Eastern Shore, where salt marsh is starting to expand into agricultural fields.

Credit: E Zambello/LTER-NCO CC BY 4.0

A Long Legacy

Victoria Long has a deep connection to the land here in Virginia’s Eastern Shore. Her family has farmed this land for generations—since 1652 to be exact. She grew up a few miles from the Virginia Coast Reserve Long Term Ecological Research (LTER) site, attended the local high school and began to work for the LTER in the footsteps of an older sister. Now, she is using her PhD research to give back to the local community.

Rising seas are not theoretical here. In this farming region, landowners have watched their coastal fields become wetter, losing 474 arable acres to intruding salt marsh each and every year. Taking me to her study sites, Long drove through small towns and skirted numerous farm fields until we arrived at the Nature Conservancy property. It may be called the Brownsville Preserve now, but when Long looks at the historic house and flat fields with waving grasses, she sees land that generations of her family once owned.

“My family’s history in the region has definitely helped open some doors as far as resources and study site availability,” Long explained. “The recognition that my name provides is enough to at least start a conversation that can have a much larger effect in the future.”

It had been drizzling off and on throughout the morning, so we trooped through the fields in raincoats and closed-toed shoes. Long had a baseball cap perched atop her red hair, and I was jealous – I wanted all the coverings possible to keep out the swarm of mosquitoes that threatened to engulf us as we marched towards her plots, marked by bright red flags waving in the breeze. Long has a quick step and can-do attitude; she grew up doing farm work with her parents and siblings. Compared to that, even the toughest field work seems easy, she told me.

Trying to Save a Way of Life

Long has multiple goals with her research. Her field is adjacent to a saltmarsh, and using vegetative plots as well as water quality sensors she is monitoring the transition from farmland to salt marsh. Grasses growing as tall as our shoulders waved as we walked through them; tall trees at the end of the fields acted as dark borders. Long’s research addresses many questions: How wet and salty does it have to be before marsh plants begin to intrude into the field? Which species encroach first? Do they stay forever or retreat back and forth depending on weather variations?

Second, Long studies how well other marketable, saltwater tolerant plant species can grow in these conditions. Perhaps if farmers cannot grow vegetables or wheat, they can try saltmarsh mallow and switchgrass, two species she is testing in preparation for a biofuel market. If these species take off as biofuel, farmers can retain their fields even with salt marsh intrusion. They can protect not only their livelihoods, but the culture of Virginia’s Eastern Shore as well.

Long’s study plots, located in an agricultural region threatened by salt marsh encroachment.

Credit: E Zambello/LTER-NCO CC BY 4.0

“Being a native helps me to understand the bigger picture when it comes to the impacts of environmental research on the Eastern Shore and spreading the word about our findings,” Long explained. “What scientists view as important may not be as important to the farmers, watermen, and landowners and it is essential to understand this distinction when reaching out to the target audience.”

Long has a, well, long view on her research: “As the daughter of a 12th generation farmer, my research is more than just my job; it directly impacts the people I love, and the place I call home.”

When I visited, she was in the middle of her time as a PhD student. She knows her research will continue after her graduate studies, taken over by a future PhD student. She has a younger sister after all. Perhaps she’s not into ecology yet (she’s only 13), but there is plenty of time!