Dr. Haddad looks at a bee box.

Credit: E Zambello/LTER-NCO CC BY 4.0

In a grassy clearing between crop hectares at the Kellogg Biological Station LTER, Dr. Nick Haddad, Principle Investigator, stares into the dark recesses of a bee box, set a few feet off the ground.

The research team places the bees here while they’re still in cocoons. When they hatch, the bees gather fluorescent yellow, powdered dye on their furry bodies before flying off across the flowering fields to find new nests.

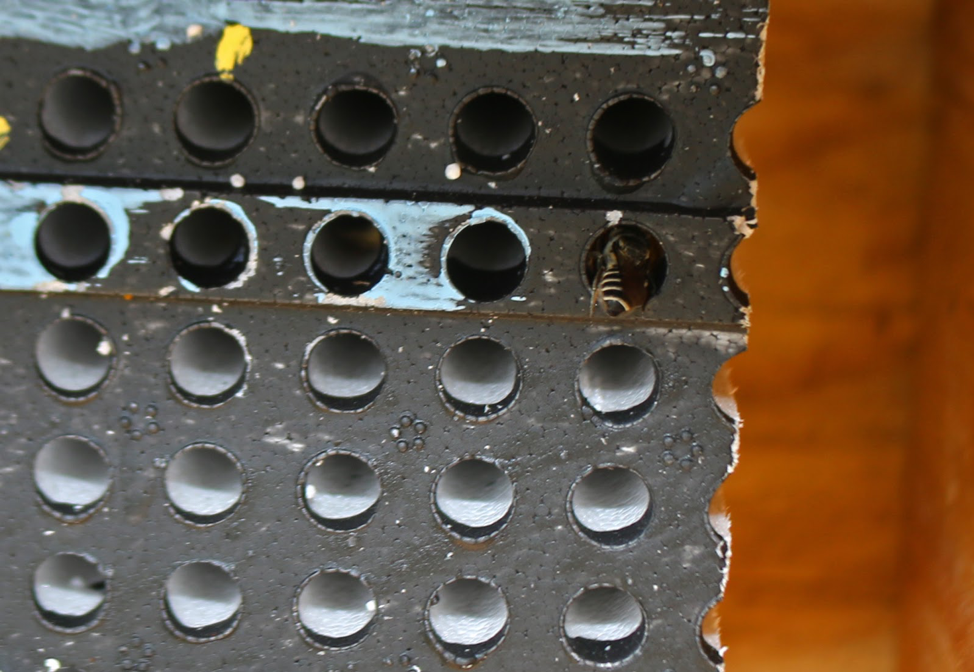

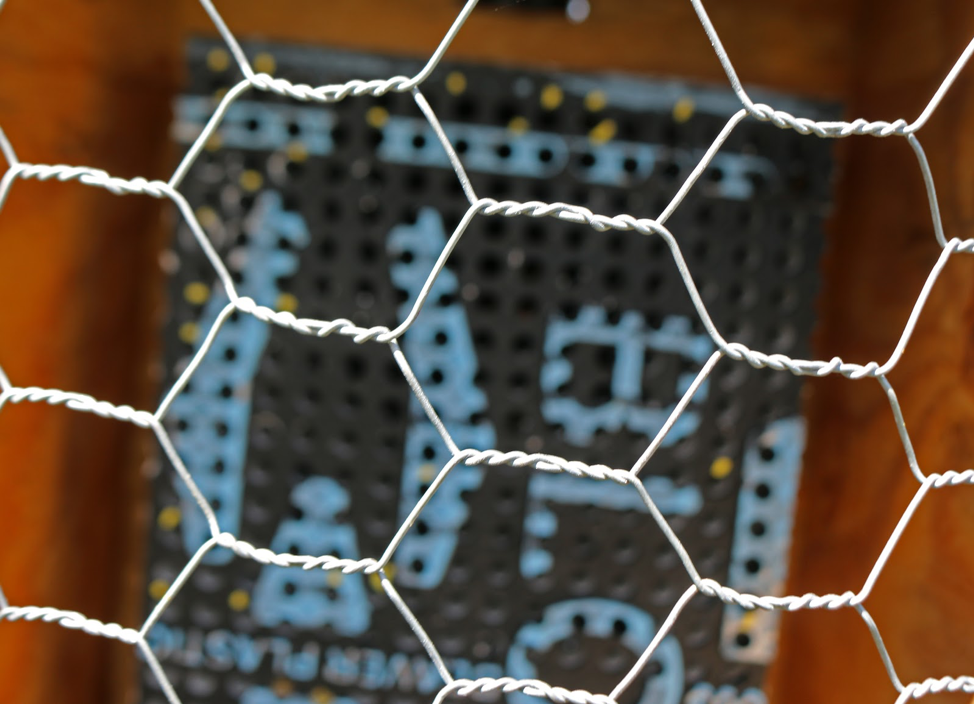

Alfafa Leafcutting Bee (Megachile rotundata) boxes like this one are set up across the LTER, each with different-colored dye, like hues from a fun run. From the bee box in the grassy walkway between crop rows, Dr. Haddad led me through a secondary successional field plot, grasses and goldenrod waving around our waists as we picked our way carefully along a nearly invisible track towards another bee box. Unlike the first, this wooden rectangle included tiny holes on the other side of a wire fence, bees moving in and out of the tiny holes. Here and there, little bee butts left their highlighter-yellow dye beneath the hole they chose to enter to lay their eggs.

Sean Griffin works in Dr. Haddad’s lab at the Kellogg Biological Station, running the bee project as part of his PhD research.

“The goal of our study was to understand how habitat and resource availability affects bee colonization of new habitats, so that we can better design pollinator habitats for native bee conservation” Griffin explains in an email.

“Using the KBS LTER, we conducted a landscape-level experiment in which we released woodnesting bees from release boxes and studied their occupation of nest boxes placed in agricultural (soy) plots, flowering successional fields, and empty/bare plots,” he continues, “We were able to track bee movement, occupation and nest building by marking individuals with fluorescent dye when they emerged and by counting nesting females at our experimental nest boxes.”

Griffin counts sleeping bees occupying nests at night, as well as nests produced and cells per nest. “Each cell has a single egg, but nests can hold 4-7 cells,” Griffin writes in an email, “All created by the same bee. The leafcutter bees create balls of pollen for each egg, and seal them in rolled-up leaves.”

A Kellogg bee box.

Credit: E Zambello/LTER-NCO CC BY 4.0

Bees – A Critical Species

Griffin has been interested in bees for over a decade. “I first started working with bees during my time as an undergrad at Cornell University under the guidance of Dr. Tom Seeley, who studies honey bee communication and nesting behavior.”

He explains: “I have always been fascinated with bees because of the complexity of their behaviors and decision making, and so I looked for ways to get involved in bee research as soon as I could. Though I’ve since switched to studying native bees, I’m still interested in the same aspects of bee ecology – how do bees see the world, and what makes them behave the way they do? Plus, bees are, in my opinion, the cutest animals!”

Griffin chose the Alfafa Leafcutting Bee because they are a woodnesting species. “They generally nest in holes in logs and trees made by woodpeckers, beetles, and other burrowing arthropods,” he explains, “Without my boxes, these bees would have nowhere to nest in the LTER plots.” Because he controls nesting resources, he can ask additional questions about habitat and nesting relationships.

“It was pretty cool to see little fluorescent bees flying across the landscape!” he added.

One of the study bees entering a bee box.

Credit: E Zambello/LTER-NCO CC BY 4.0

Bees form critical pollinator populations for both agricultural crops and the natural prairie. “Bees are super diverse and widespread, and have adapted to a huge number of habitats around the world,” Griffin says. Unfortunately, their numbers are experiencing a steep decline. Understanding the bees and their nesting behavior is critical to conserve them, “both to protect the pollination services we need,” Griffin tells me, “as well as for their owns sake, because they are beautiful and diverse.”

Initial Results

After a season of field data, Griffin found that the bees are nesting in areas with more flowers, as the flowering plants make up their food sources. “This indicates that though nest sites are limiting for many bees,” Griffin concludes, “They may still make nesting decisions based on other resources, and indicates they may assess the suitability of an area for nesting before creating their nests.”

As we left the nest boxes, tracing the outline of a native plant plot, I focused my attention on the bright flower petals and the bees gathering food before zipping back to their chosen nest boxes. With the help of the Kellogg LTER team, they will continue to play their critical fertilizing role into the future.

Staring into a bee box.

Credit: E Zambello/LTER-NCO CC BY 4.0