Zebra mussels attach to hard bottom structure.

Credit: E Zambello/LTER-NCO CC BY 4.0

In 2015, a group of undergraduates from the University of Wisconsin, Madison launched boats into Lake Mendota at the edge of campus, ready to put lessons from the classrooms to the test in hands-on field research activities. As they moved through research protocols, a student brought a metal pole from the soft bottom to the surface of the lake.

Vince Butitta, the graduate student teaching assistant, noticed a small bivalve attached to the end of the pipe, and his stomach dropped. The undergrads had just discovered the first recorded Zebra Mussel in Lake Mendota.

Boating across Lake Mendota.

Credit: E Zambello/LTER-NCO CC BY 4.0

Zebra Mussels are “an invasive, fingernail-sized mollusk that [are] native to fresh waters in Eurasia. Their name comes from the dark, zig-zagged stripes on each shell.” First discovered in the Great Lakes in the 1980s, they have since colonized freshwater bodies across the Midwest and even California, Texas, Colorado, Utah, Nevada, and North Carolina. In addition to eating the algae that native bivalves depend on, Zebra Mussels can also “attach to–and incapacitate–native mussels.”

Monitoring the Mussels

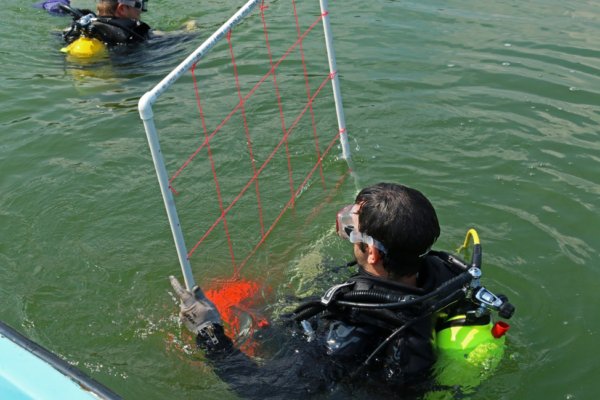

Fast forward three years, as the North Temperate Lakes Long Term Ecological Research Site (LTER) sampling team pulled on wetsuits and organized scuba gear for a sampling survey of zebra mussels in transects within the lake, starting from the University of Wisconsin Limnology Lab. Carefully balancing my camera, I stepped onto the Boston Whaler boat, shielded my eyes against the late summer glare and watched Madison grow smaller as we headed a short distance to the study site.

The team dives to count mussels using transects.

Credit: E Zambello/LTER-NCO CC BY 4.0

Petra Wakker, an undergraduate student at the university, monitored the boat from above. Dane McKittrick, another rising senior, and Mike Spear, a PhD student in his 3rd year at the Center for Limnology, leaned back and fell off the boat into the water, disappearing in a cloud of bubbles as they surveyed the bottom. Earlier in the morning, water clarity had been so good that Petra could easily track their progress, but the noon-time heat had caused a proliferation of blue-green algae, and now only their breath gave away the dive location.

Returning to the surface, Mike and Dane came up with a sample similar to what the NTL researchers found in 2015: a few mussels here and there, attached to a hard surface. Back then, the scientists could easily count every single mussel they found in their 1 x 1 m plots.

An Invasion

That would be impossible today. We motored to another spot, and Mike came over to the side of the boat with a piece of broken concrete absolutely covered in Zebra Mussels. Initially, the researchers counted the species with tweezers; they now shovel mussels into weighing bags with a paint scraper, sometimes estimating as many as 50,000 mussels per square meter.

Zebra Mussels need structure to attach and survive, so despite their high density they remain confined to the edge of the lake. Still, based on the decades of data NTL has collected since its funding began in 1981, staff have already noticed changes in water parameters as well as in the algae community. Though the invasion is only three years old, the Zebra Mussels have gobbled up native algae in the lake but literally spit out the blue-green algae, which now more often multiplies into the kind of bloom I witnessed.

Dane holds two mussel-encrusted concrete pieces.

Credit: E Zambello/LTER-NCO CC BY 4.0

In addition to harming native species within the lake, these mussels cost the local cities and businesses millions of dollars. According to one Sea Grant report, “They clog water intakes for municipalities and industries, foul boat hulls, motors, water-related equipment and shipwrecks. They can decrease property values. Sharp shells can litter beaches, cut feet and affect recreation and tourism. Overall, zebra mussels harm our environment, recreation and the economy of communities that depend upon healthy lakes and rivers.”

NTL LTER hopes that by taking advantage of this rare opportunity to study an invasion from the beginning, they can innovate management strategies to not only keep this detrimental mussel from taking over the entire lake, but also prevent its spread to other nearby lakes.