A research boat flies through the chop.

Credit: Sloane Viola

As our boat cut through the chop of the Santa Barbara Channel, sending fans of spray hissing in our wake, I couldn’t help but appreciate the beautiful day and consider how fortunate I was that my job requires regular SCUBA diving. While relishing this blissful feeling and the glorious weather, I noticed that my fin strap was loose. We were in between two quick dives at the oil platforms off of Santa Barbara, and had all of our gear on so we could immediately jump in at our next dive site. As I reached down to adjust my fin, the boat hit a particularly large swell, causing it to heave unexpectedly, sending me flying backwards in an awkward tumble off the side of the boat and into the Pacific. That sunny glow I had been feeling was immediately replaced by shock at how quickly I was thrown, embarrassment for not paying attention, and amusement at the baffled faces of my dive team as the boat wheeled around to retrieve me from the ocean.

An oil rig in the Santa Barbara Channel.

Credit: Sloane Viola

Field research abounds with moments like these, where a switch flips and a routine day suddenly turns into chaos. These hurdles range from minor to major: weather conditions or platform operations have kept us from diving on schedule, equipment has fall to the depths of the ocean, a housing once failed and ruined an expensive camera, and I’m guilty of forgetting water or food out on the boat. I have to remind my envious friends that it’s not all fun and games out in the field, and that sometimes I have to overcome logistical, physical, and mental blocks that could potentially hinder successful research. However, these experiences, for lack of a better term, build character. I’ve learned to take things in stride and be a creative problem-solver. I understand my limits, but feel so accomplished when I challenge myself and succeed. Though I would consider myself to be a detail-oriented micro-manager at times, I’ve learned to be relaxed and flexible with on-the-fly decision making.

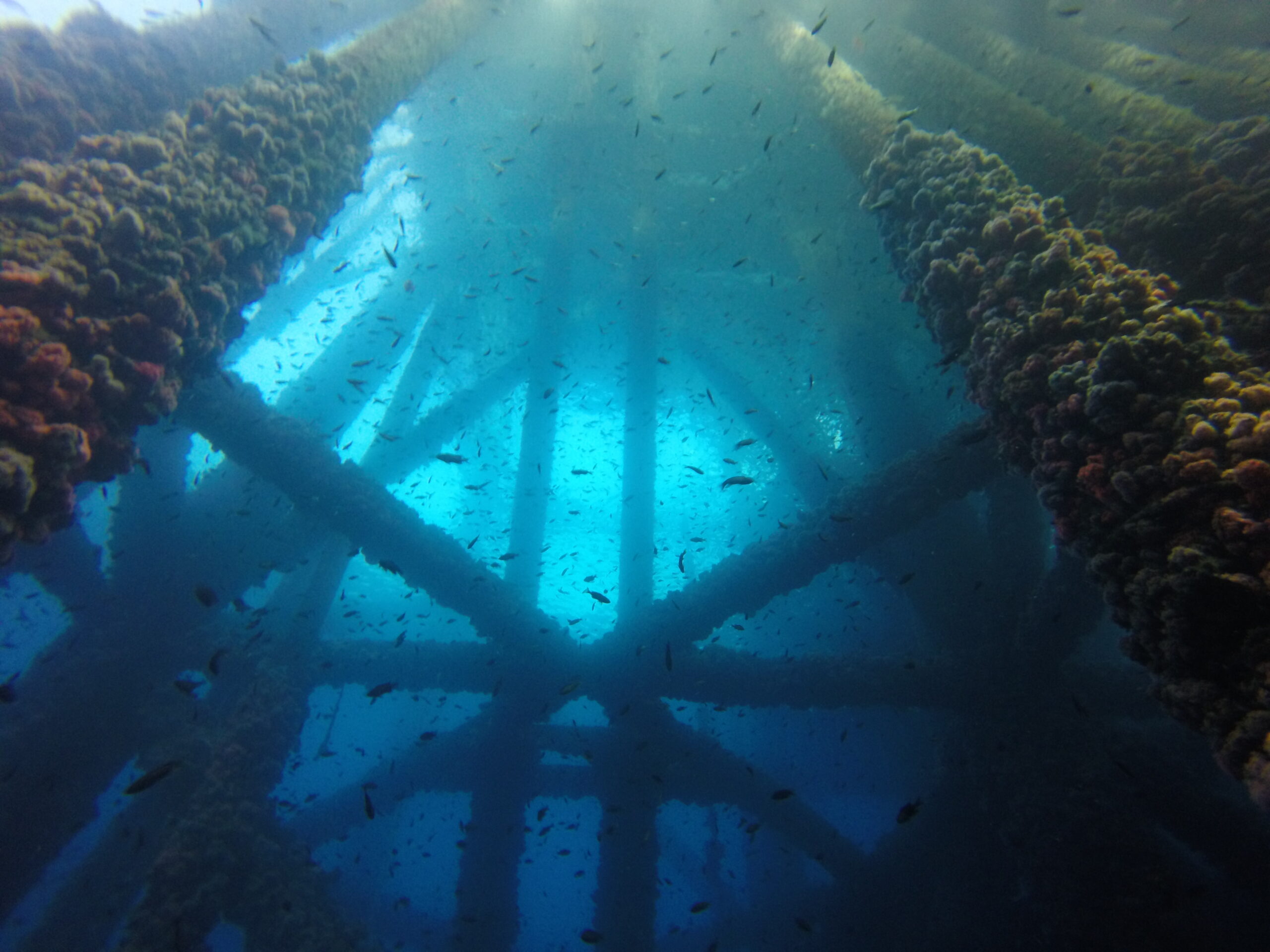

Fish congregate under the structure oil rigs provide.

Credit: Sloane Viola

If nothing else, the challenging days make me truly appreciate the good days that make it all worthwhile. Diving at the oil platforms is breathtaking in ideal conditions. Visibility can reach 100 feet, far more than a good day on the mainland. Huge schools of juvenile fish, large adult fish, and elusive pelagic species make appearances out at the platforms.

On the pilings under the rigs, invertebrate life thrives.

Credit: Sloane Viola

The invertebrate community growing on the platform’s structure is rich and vibrant; pink, purple, and peach strawberry anemones abound, shrimp dart around mussel and scallop shells, and millions of barnacles wave their feeding combs. Playful sea lions curiously swim by and pirouette as if putting on a show.

The vibrant marine life attracts large mammals looking to eat, too. Here, two sea lions dive into the depths.

Credit: Sloane Viola

Before I started this thesis, another graduate student told me about the trials and tribulations of her thesis work. She told me that one needs a sense of humor when conducting a laboratory experiment. I can’t help but wonder if that means that someone doing a field work needs the sense of humor of a true comedian, because there is even more room for setbacks in the field. In spite of the challenges, I wouldn’t dream of exclusively working out of a laboratory or office; the rewards of fieldwork are a regular affirmation of my choice to pursue a career in ecology.

And, as researchers, we’re right down there too.

Credit: Sloane Viola

I am a second year Master’s student at the University of California, Santa Barbara studying the effects of disturbance and community dynamics on the colonization success of a non-native marine epibenthic invertebrate on offshore structures. Prior to starting this research, I worked as an undergraduate intern and then a lab technician in a beach ecology research lab at UCSB. I did an undergraduate thesis on the effects of fine sediments from nourishment material on the burrowing ability of beach invertebrates. When I’m not being a scientist, I play beach volleyball and kickball, surf, hike, read, and I’ve been building a ukulele.