LTER Road Trip: Real Time Evolution

Salamanders are very sensitive to changes in both precipitation and temperature, and scientists at the Coweeta Hydrologic Lab have discovered that they represent a hotbed of evolutionary activity. That’s right – evolution is happening before our eyes, in real time.

International Drought Experiment" data-envira-gallery-id="site_images_46804" data-envira-index="5" data-envira-item-id="82314" data-envira-src="https://lternet.edu/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/Matta_rainout-533x400.jpeg" data-envira-srcset="https://lternet.edu/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/Matta_rainout-533x400.jpeg 400w, https://lternet.edu/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/Matta_rainout-533x400.jpeg 2x" data-title="Matta_rainout" itemprop="thumbnailUrl" data-no-lazy="1" data-envirabox="site_images_46804" data-automatic-caption="Matta_rainout -

International Drought Experiment" data-envira-gallery-id="site_images_46804" data-envira-index="5" data-envira-item-id="82314" data-envira-src="https://lternet.edu/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/Matta_rainout-533x400.jpeg" data-envira-srcset="https://lternet.edu/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/Matta_rainout-533x400.jpeg 400w, https://lternet.edu/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/Matta_rainout-533x400.jpeg 2x" data-title="Matta_rainout" itemprop="thumbnailUrl" data-no-lazy="1" data-envirabox="site_images_46804" data-automatic-caption="Matta_rainout -

E Zambello/LTER-NCO

E Zambello/LTER-NCO  E Zambello/LTER-NCO

E Zambello/LTER-NCO  E Zambello/LTER-NCO

E Zambello/LTER-NCO

Ingrid Taylar.

Ingrid Taylar.  Chesapeake Bay Program. CC BY-NC 2.0." data-envira-gallery-id="site_images_46804" data-envira-index="24" data-envira-item-id="46942" data-envira-src="https://lternet.edu/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/30914015212_906755c25b_k-600x400.jpg" data-envira-srcset="https://lternet.edu/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/30914015212_906755c25b_k-600x400.jpg 400w, https://lternet.edu/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/30914015212_906755c25b_k-600x400.jpg 2x" data-title="30914015212_906755c25b_k" itemprop="thumbnailUrl" data-no-lazy="1" data-envirabox="site_images_46804" data-automatic-caption="30914015212_906755c25b_k - Forest buffer in Baltimore County, MD. Chesapeake Bay Program. CC BY-NC 2.0." data-envira-height="200" data-envira-width="300" />

Chesapeake Bay Program. CC BY-NC 2.0." data-envira-gallery-id="site_images_46804" data-envira-index="24" data-envira-item-id="46942" data-envira-src="https://lternet.edu/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/30914015212_906755c25b_k-600x400.jpg" data-envira-srcset="https://lternet.edu/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/30914015212_906755c25b_k-600x400.jpg 400w, https://lternet.edu/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/30914015212_906755c25b_k-600x400.jpg 2x" data-title="30914015212_906755c25b_k" itemprop="thumbnailUrl" data-no-lazy="1" data-envirabox="site_images_46804" data-automatic-caption="30914015212_906755c25b_k - Forest buffer in Baltimore County, MD. Chesapeake Bay Program. CC BY-NC 2.0." data-envira-height="200" data-envira-width="300" />

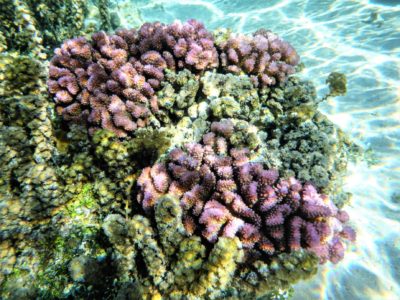

CC BY-SA 4.0" data-envira-gallery-id="site_images_46804" data-envira-index="36" data-envira-item-id="46180" data-envira-src="https://lternet.edu/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/P7193263-copy-600x400.jpg" data-envira-srcset="https://lternet.edu/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/P7193263-copy-600x400.jpg 400w, https://lternet.edu/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/P7193263-copy-600x400.jpg 2x" data-title="Crown-of-thorns Sea Star" itemprop="thumbnailUrl" data-no-lazy="1" data-envirabox="site_images_46804" data-automatic-caption="Crown-of-thorns Sea Star -

CC BY-SA 4.0" data-envira-gallery-id="site_images_46804" data-envira-index="36" data-envira-item-id="46180" data-envira-src="https://lternet.edu/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/P7193263-copy-600x400.jpg" data-envira-srcset="https://lternet.edu/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/P7193263-copy-600x400.jpg 400w, https://lternet.edu/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/P7193263-copy-600x400.jpg 2x" data-title="Crown-of-thorns Sea Star" itemprop="thumbnailUrl" data-no-lazy="1" data-envirabox="site_images_46804" data-automatic-caption="Crown-of-thorns Sea Star -