LTER Road Trip: Music and Art Meets Science at Hubbard Brook

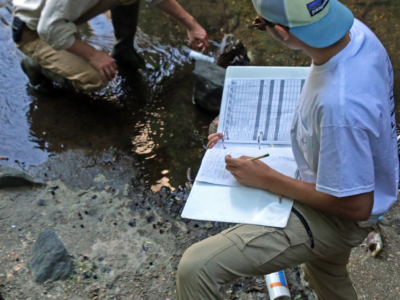

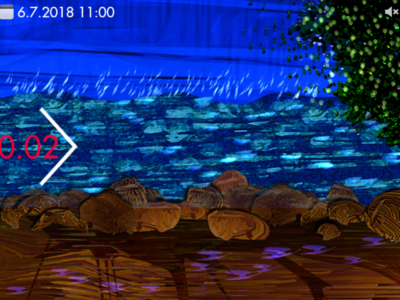

Envisioning Data at Hubbard Brook It’s not every day that you walk into a forest and find musical instruments set up carefully next to a gurgling stream. Yet melding art and science together is a regular part of the day-to-day operations at the Hubbard Brook Experimental Forest. Imagine the way that scientific data is normally… Read more »