Like marine fog that blankets one community while leaving a nearby neighborhood in sunshine, COVID 19 crept up on us at an uneven pace. In California, awareness and action to halt its spread came quickly, with in-person instruction at UC Santa Barbara, where the LTER Network Office is located, halted on March 11 and virtually all research operations halted on March 20, 2020. But our role — as a hub for the 28 sites of the LTER Network — gives us a window into the dilemmas that ecologists across the country are facing as they come to terms with this pandemic.

A diver tags individual kelp stipes at the Santa Barbara Coastal LTER. Underwater research, which requires a dive buddy and travel in small boats, poses a particular dilemma during COVID19 isolation.

Credit: Santa Barbara Coastal LTER.

For researchers in states with do-not-work orders or from institutions that have shuttered their research operations, there may be no decision to make about whether to continue field work. But those that the virus has been slow to find are now faced with a choice: continue field measurements and manipulations or halt them voluntarily and accept the cost to their science and sometimes their budgets.

For LTER sites and other long term measurement programs, the cost is substantial. Long time series often represent decades of effort by dozens of scientists and losing even a few weeks of data during key transitions (such as snow melt, leaf out, or a spring phytoplankton bloom) is equivalent to losing the whole year. Disturbance and resilience are central themes for many LTERs. Losing key data points in periods of dynamic change (such as the spring following an experimental ice storm or the summer that a lengthy drought breaks) can effectively mean starting from scratch to recreate that experiment or waiting for that unique set of conditions to recur.

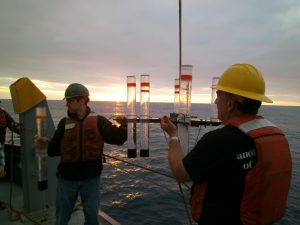

COVID 19 isolation has required the first substantial break in a 50-year dataset maintained by California Cooperative Oceanic Fisheries Investigations (CalCOFI) and the California Current Ecosystem LTER.

Credit: A. Giraldo Lopez/CCE LTER

Choosing whether to maintain long term experiments during this time poses an even more difficult dilemma. A break in fertilizer, CO2, rainfall, or seawater manipulations doesn’t just mean missing a year of data, it changes the entire experiment. The quarantine-related pause in human activities is also an experiment on a scale that cannot be recreated and foregoing the opportunity to collect related data is nearly unbearable for many ecologists.

At the same time, the image of a solo ecologist at a remote field site suggests that it may be possible to stay safe while maintaining some field-based measurements. After all, how is measuring snow depth different from cross-country skiing for exercise? Is collecting lysimeter samples so different from a hike in the woods? When — and how — do we tell graduate students that it’s OK to go for a run on neighborhood streets, but not OK to install the experiment they’ve spent all winter designing?

These are thorny questions that we must each tackle as we decide whether to request an exemption to university research closures and — as the peak of the pandemic passes — when and how to return to the field. Circumstances in rural Alaska are quite different than in coastal California or downtown Phoenix. So our answers will differ, but here are a few questions that LTER researchers are asking ourselves as we try to move forward responsibly.

- What would be different if I delayed these measurements until next month or next year?

Would postponing measurements be a simple trade-off? Would it mean losing years of effort and extraordinary financial investment? All field seasons are unique, but some hold more potential for insight than others. Include realistic estimates of the risks and benefits in your decision making. - Can I maintain 2 meters of separation at all times (on the way to the site, in lodgings, at meals, in the event of an accident)?

It may be possible to stay 2 meters apart while underwater or at a remote field site, but not so simple while in a small boat or staying in a field site residence. Does your workflow require you to hand off samples or equipment? What if you experience an accident in the field? Do you want to be responsible for drawing medical personnel and equipment away from the virus response? - Could everyone involved decline to participate if they didn’t feel safe? Would there be financial or career consequences and can they be mitigated?

We all have different vulnerabilities. Some have invisible health conditions; some greater financial concerns; some find it difficult to disappoint those with authority or status. Even as some researchers feel perfectly safe continuing or re-starting field work, it may not be possible or reasonable for all. Am I attending to the concerns of everyone on my team and recognizing power differences? -

Although automated sampling continues at many locations during COVID19 isolation, eventually, data will need to be downloaded, samples retrieved and equipment maintained.

Credit: Luquillo LTER. CC BY-SA 4.0Is there another way to fill the data gap, such as remotely sensed or automated data collection?

Although remotely sensed data may not be a perfect fit for my question, could I use it as a proxy or stopgap to estimate parameters I would normally measure in the field, especially when combined with previous and future field measurements. - Can I develop creative ways to move the research forward and keep students and technicians employed?

The Environmental Data Initiative (environmentaldatainitiative.org) houses 40 years of data from Long Term Ecological Research (LTER) sites, along with data from many other projects, available in a few keystrokes. DataONE (https://www.dataone.org/) offers access to an even larger universe of environmental data. Are there questions adjacent to my field studies that could draw on past data collections? - What would a casual observer think? Might it change their behavior? Or their opinion of scientists?

Even if I think my research could be carried out in complete safety, it makes sense to consider the impact it could have on my community. Am I comfortable launching a small research vessel when boat ramps are closed to the public? Could such actions lead others to take precautions less seriously? Might travel introduce the virus to communities that aren’t yet experiencing it?

There is no one-size-fits-all answer to these questions. At some of our remote sites, essential field crews are already in place and leaving would expose them to greater risk than staying where they are. So they are collecting data as they are able for those who cannot travel. At other sites, data loggers and autosamplers are working away, but will soon run out of battery power or storage. If one excursion would allow them to keep sampling for another six months, is it worth the risk? The decisions are difficult, especially when it is unclear how long the situation will continue. Choices we make now will affect the career trajectories of graduate and undergraduate students who are just getting in the field for the first time.

Regardless of how individual sites and scientists resolve these questions, we can all pull together in creating opportunities to access and analyze existing data, mentor students and early-career scientists, and build our collaborative community. When we look back in a few years, I hope we will mark 2020 as a challenge that made us stronger, better, and kinder — even if it does leave a few gaps in our datasets.

—By the LTER Network Office (Marty Downs, Frank Davis,

Jenn Caselle, Julien Brun, and Kristen Weiss), based on

conversations with many LTER investigators and students

This post was first published on the Ecological Society of America’s Ecotone blog as a contribution to their COVID19 resources.