Research programs at 26 LTER sites support ecological discovery

on the influence of long-term and large-scale phenomena.

MISSION

Mission: The LTER mission is to create knowledge, inspire solutions, and cultivate learning through inclusive and interdisciplinary long-term ecological research.

Vision

Vision: At the network scale, we envision synergy arising from collaborations among investigators working at long-term research sites across diverse ecosystems. This synergy will accelerate discoveries that enhance the welfare of society and the environment.

VALUES

Values: Each LTER site is rooted in place-based, hypothesis-driven long-term ecological research; however, the Network’s synergistic power stems from linking these sites into a collaborative whole.

As an LTER Network we aspire to embody open, rigorous, and inclusive science. We value a deep understanding of ecosystems and transformative outcomes for our science and the people involved. We believe that deliberate collaboration and active exchange of ideas produce synthetic knowledge of emergent properties that lead to a more universal understanding of the natural world.

We feel a responsibility to society through advancing and sharing knowledge, informing decision making, and responsible stewardship. By embracing these values, we aim to produce tangible and intangible outcomes at the Network level that are greater than what could be achieved by individual sites.

Goals

Understanding

To understand a diverse array of ecosystems at multiple spatial and temporal scales.

Synthesis

To create general knowledge through long-term, interdisciplinary research, synthesis of information, and development of theory.

Outreach

To reach out to the broader scientific community, natural resource managers, policymakers, and the general public by providing decision support, information, recommendations, and the knowledge and capability to address complex environmental challenges.

Education

To promote training, teaching, and learning about long-term ecological research and the Earth’s ecosystems, and to educate a new generation of scientists.

Information

To inform the LTER and broader scientific community by creating well-designed and well-documented databases.

Legacies

To create a legacy of well-designed and documented long-term observations, experiments, and archives of samples and specimens for future generations.

Core Themes

Five core research themes have been central to LTER Network science since it was established by the U.S. National Science Foundation in 1980. Research in these core areas requires the involvement of many scientific disciplines, over long time spans and broad geographic scales. Data on the core areas are collected to establish and understand the existing conditions in an ecosystem before any experimental manipulation is begun.

The common focus on core areas facilitates comparison among and across sites in the Network.

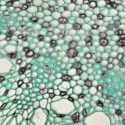

Credit: Clare Nemes

Primary Production – Plant growth in most ecosystems forms the base or “primary” component of the food web. The amount and type of plant growth in an ecosystem helps to determine the amount and kind of animals (or “secondary” productivity) that can survive there. Read LTER research stories related to primary production.

Population Studies – Populations of plants, animals, and microbes change in space and time, moving resources and restructuring ecological systems. Read LTER research stories related to population studies.

Movement of Organic Matter – An entire ecosystem relies on the recycling of organic matter (and the nutrients it contains), including dead plants, animals, and other organisms. Decomposition of organic matter and its movement through the ecosystem is an important component of the food web. Read LTER research stories related to organic matter movement.

Nutrient Cycling – Nitrogen, phosphorus, and other mineral nutrients are cycled through the ecosystem by way of decay and disturbances such as fire and flood. In excessive quantities nitrogen and other nutrients can have far-reaching and harmful effects on the environment. Read LTER research stories related to mineral cycling.

Disturbance Patterns – Disturbances often shape ecosystems by periodically reorganizing structure, allowing for significant changes in plant and animal populations and communities. Read LTER research stories related to disturbance patterns.

Two additional themes emerged with the addition of urban LTER sites, but it has become clear that they are also relevant for the rest of the Network:

Land Use and Land Cover Change: examine the human impact on land use and land-cover change in urban systems and relate these effects to ecosystem dynamics. Read LTER research stories related to land use and land cover change.

Human-Environment Interactions: monitor the effects of human-environmental interactions in urban systems, develop appropriate tools (such as GIS) for data collection and analysis of socio-economic and ecosystem data, and develop integrated approaches to linking human and natural systems in an urban ecosystem environment. Read LTER research stories related to human-environment interactions.

LTER sites also serve the wider ecological community by:

Making more than 45 years of sustained observations publicly available

Developing and maintaining large-scale experiments, which provide starting conditions for process-level studies, help to parameterize and test model, and spur cross-site synthesis

Providing long-term context and deep knowledge of place for researchers working on shorter-term projects

Training hundreds of graduate students in interdisciplinary and collaborative team science

LTER sites are the core of the Network

Each LTER site involves dozens of researchers, typically including microbial, community, and landscape ecologists, but also hydrologists, geochemists, social scientists, economists, and even sometimes artists and humanities scholars.

The shared knowledge of place offers unusual common ground for exploring disciplinary intersections.

Education and outreach helps LTER science make an impact

The longer tenure of LTER sites also makes them particularly well-suited to developing the relationships needed to engage with stakeholders, educators, and the public.

All LTER sites have an education and outreach component, although the exact nature of the program varies by site. Remote forested sites may deal mainly with foresters and landowners, while urban sites may more closely engage community residents.

Data, especially data management, play a crucial role

The value of LTER’s long-term data resource is immense and LTER data managers have been leaders in the movement to ensure that ecological data is accessible and usable.

Dedicated information managers document and archive LTER data in public repositories so that they can be re-used by the broader scientific community.

The Environmental Data Initiative (EDI) is LTER’s primary data repository and has a strong record of serving FAIR (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reproducible) data. Occasionally, LTER datasets reside in disciplinary- or geographically-focused repositories and EDI maintains metadata referencing the full dataset.

Well into its fourth decade, the LTER’s long-term experiments continue to reveal surprising insights only gleaned through long-term study.

We can’t wait to see what the next fifty years bring.